1. Introduction

Welcome to the AI Ethics program! Here are a few key things to know about how the program is structured. Throughout the course, you’ll have access to materials in both text and audio formats. In many sections, you’ll find audio narration alongside the text—just click play and follow along at your own pace.

Program Structure

Sprint contain multiple parts. Each part includes written content, accompanied by voice guide. You should go through the content as it is arranged.

After completing each part, you will need to complete a quiz that will allow you to test your knowledge. The quizzes on the Turing platform are meant for self-evaluation — do not be discouraged if you answer some incorrectly because there are absolutely no penalties for that. Instead, if you get some answers wrong, work on figuring out why the correct answer is different.

Finally, after completing the theory-focused parts of each sprint, you will get to work on practical projects. These projects are usually the final parts of each sprint - the current sprint has one, too. Practical projects and project reviews are among the main unique benefits that you will receive as a student at Turing College. To progress to the next sprint, you will need to participate in a live 1-1 call scheduled through the platform with our Turing College mentors. More will be explained in the final Part of this Sprint.

Revision of core Turing College concepts

If you haven’t done so before, be sure to read the following documents about the core aspects of Turing College. The first quizzes may even contain questions that will test your understanding of these topics.

Core Turing College Concepts

In addition to the events mentioned above, AI Ethics learners will have access to dedicated Learning Sessions. These sessions provide an opportunity to engage with a mentor to explore topics in greater depth, share perspectives, and clarify your understanding. You can also use this time to offer feedback on your learning experience. You will find the Learning Sessions on your calendar.

Each part of the program begins with an introduction and is divided into several units. These units are organized within collapsible menus. Be sure to go through all units in a part before moving on to the next one.

Now, let’s dive in!

Context

Sprint 1 establishes the foundation for all subsequent fairness work, focusing on assessment methodology before technical interventions. Without systematic assessment, fairness efforts often target symptoms rather than causes.

This Sprint builds the groundwork for later work: Sprint 2 covers technical intervention strategies, Sprint 3 explores organizational implementation, and Sprint 4A translates concepts into code. The Sprint Project follows a domain-driven approach, working backwards from our desired outcome—a fairness assessment methodology—to its necessary components.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this Sprint, you will:

- Analyze how historical patterns of discrimination manifest in AI systems by mapping bias mechanisms to data attributes and model behaviors.

- Select appropriate fairness definitions based on application context by navigating mathematical fairness formulations.

- Identify potential bias sources throughout the ML lifecycle by mapping where bias enters systems.

- Translate ethical principles into concrete evaluation procedures by connecting abstract values to assessment techniques.

- Develop assessment methodologies that integrate multiple fairness dimensions by synthesizing historical, definitional, and technical components.

Sprint Project Overview

Project Description

In Sprint 1, you will develop a Fairness Audit Playbook—a methodology for evaluating AI systems across multiple fairness dimensions. This framework assesses whether AI systems perpetuate historical biases, how they align with fairness definitions, where bias enters systems, and how these issues manifest in measurable outcomes.

The Playbook operationalizes fairness through historical analysis, precise definitions, bias identification, and measurement—creating accountability through documented evaluation processes.

Project Structure

The project builds across five Parts, with each developing a critical component:

- Part 1: Historical Context Assessment Tool—identifies historical discrimination patterns and maps them to application risks.

- Part 2: Fairness Definition Selection Tool—guides selection of appropriate fairness definitions.

- Part 3: Bias Source Identification Tool—locates potential bias entry points throughout the AI lifecycle.

- Part 4: Fairness Metrics Tool—provides approaches for measuring fairness.

- Part 5: Fairness Audit Playbook—synthesizes these components into a cohesive methodology.

Historical patterns from Part 1 inform fairness definition selection in Part 2, which guides bias source identification in Part 3, which shapes metric selection in Part 4. All components integrate through standardized workflows in Part 5.

Key Questions and Topics

How do historical patterns of discrimination manifest in modern AI systems, and how can historical analysis identify high-risk applications?

Many AI systems continue patterns of discrimination established in pre-digital systems through mechanisms that appear neutral but reproduce historical inequities. Examples include predictive policing algorithms that reinforce over-policing or lending algorithms that reproduce redlining practices. The Historical Context Assessment Tool you'll develop creates a methodology for identifying relevant historical patterns and mapping them to system risks, helping pinpoint which applications require scrutiny.

How do we translate abstract fairness concepts into precise mathematical definitions, and how do we select appropriate definitions for specific contexts?

Fairness encompasses multiple mathematical definitions that operationalize different ethical principles. A central challenge is that multiple desirable fairness definitions cannot be simultaneously satisfied. For example, choosing between equal opportunity and demographic parity represents a choice about prioritizing meritocratic principles or representation goals. The Fairness Definition Selection Tool you'll develop will provide guidance for navigating these trade-offs, creating transparency around fairness priorities in specific contexts.

Where and how does bias enter AI systems throughout the machine learning lifecycle, and what methodologies enable tracing unfairness to specific sources?

Different bias types require different mitigation strategies. Historical bias stemming from societal inequities requires different interventions than representation bias from sampling procedures. The Bias Source Identification Tool you'll develop enables assessment of which bias types are most relevant for specific applications and where they enter the system, transforming bias identification from an ad hoc process to a methodical approach.

How do we quantify fairness through metrics, and how should we address statistical challenges when measuring fairness?

Fairness measurement requires translating abstract definitions into concrete metrics. Measurement without statistical validation can lead to spurious conclusions, particularly when comparing performance across groups with different sample sizes. The Fairness Metrics Tool you'll develop provides metric definitions, validation approaches, and reporting formats for empirical assessment, enabling you to determine whether systems achieve their intended fairness goals.

Part Overviews

Part 1: Historical & Societal Foundations of AI Fairness examines how historical patterns of discrimination manifest in technology. You will analyze historical continuity in technological bias, representation politics in data systems, and technology's role in social stratification. This Part culminates in developing the Historical Context Assessment Tool, which identifies historical patterns relevant to specific AI applications and maps them to potential system risks.

Part 2: Defining and Contextualizing Fairness explores translating abstract ethical concepts into precise mathematical definitions. You will examine philosophical foundations, mathematical formulations, and tensions between different fairness criteria. This Part concludes with developing the Fairness Definition Selection Tool, a methodology for selecting appropriate fairness definitions based on application context, ethical principles, and legal requirements.

Part 3: Types and Sources of Bias investigates where and how bias enters the machine learning lifecycle. You will develop a taxonomy of bias types, examine how different biases manifest at different pipeline stages, and create methods for bias identification. This Part culminates in developing the Bias Source Identification Tool, a framework for locating potential bias entry points throughout the ML lifecycle.

Part 4: Fairness Metrics and Evaluation focuses on quantifying fairness through metrics. You will learn to translate fairness definitions into measurable criteria, implement statistical validation, and communicate results. This Part concludes with developing the Fairness Metrics Tool, a methodology for selecting, implementing, and interpreting fairness metrics.

Part 5: Fairness Audit Playbook synthesizes the previous components into a cohesive assessment methodology. You will integrate historical context, fairness definitions, bias sources, and metrics into standardized workflows with clear documentation. This Part brings all components together into the complete Fairness Audit Playbook, enabling systematic fairness evaluation across diverse AI applications.

Part 1: Historical & Societal Foundations of AI Fairness

Context

Understanding historical discrimination patterns is essential for effective AI fairness work. This Part establishes a framework for analyzing how historical biases manifest in AI systems, teaching you to recognize AI biases as manifestations of longstanding discrimination patterns rather than isolated technical problems.

Technologies consistently reflect and reinforce social hierarchies—from medical technologies calibrated for male bodies to speech recognition systems performing poorly for non-native accents. These patterns persist across technological transitions. Data categorization systems (like census categories for race or medical classification systems) embed political assumptions that shape who benefits or faces harm when these practices inform contemporary datasets.

Throughout history, technologies have both reflected social hierarchies and reinforced them. Mid-20th century mortgage lending technologies encoded redlining practices, while today's algorithmic systems may reproduce similar patterns through variables correlated with protected attributes.

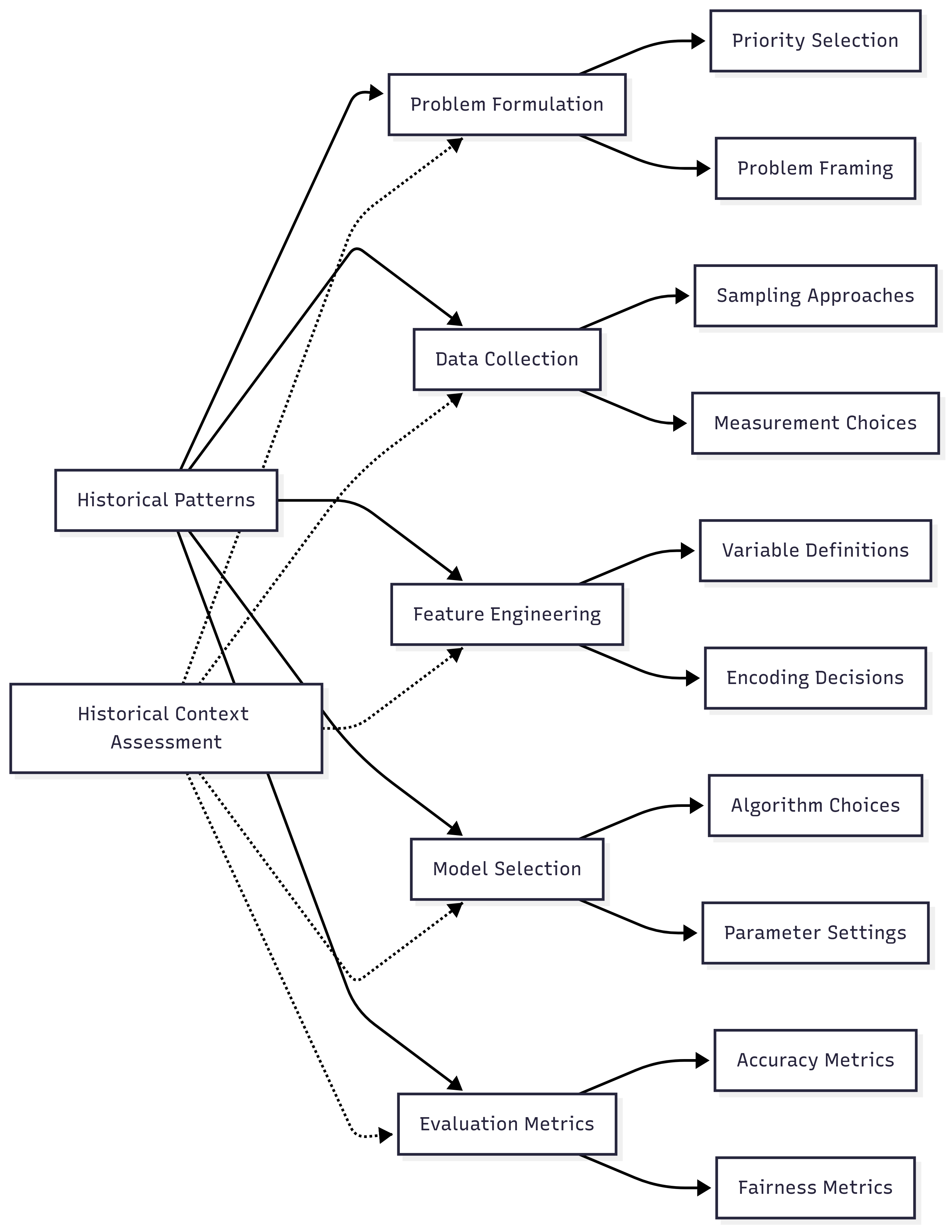

Historical patterns manifest across ML system components—from problem formulation to data collection, feature engineering, evaluation metrics, and deployment contexts. Furthermore, discrimination operates through complex interactions between multiple forms of marginalization, requiring intersectional analysis that examines how protected attributes interact rather than treating each in isolation.

The Historical Context Assessment Tool you'll develop in Unit 5 represents the first component of the Fairness Audit Playbook (Sprint Project). This tool will help you identify relevant historical discrimination patterns for specific AI applications and map them to potential system risks, ensuring interventions address root causes rather than symptoms.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this Part, you will be able to:

- Analyze how historical patterns of discrimination manifest in technology. You will identify recurring mechanisms through which historical biases persist across technological transitions, recognizing how seemingly neutral design decisions can encode discriminatory patterns.

- Evaluate how social contexts shape data representation. You will examine how power relations influence data collection, categorization, and representation practices, enabling critical assessment of data sources and representation choices.

- Apply ethical frameworks to historical fairness analysis. You will utilize various ethical perspectives to evaluate fairness across different cultural and temporal contexts, enabling navigation of complex normative questions.

- Identify high-risk AI applications based on historical patterns. You will systematically connect historical discrimination patterns to specific AI applications, enabling proactive fairness interventions focused on high-risk domains.

- Develop intersectional approaches to historical analysis. You will create analytical approaches examining how multiple forms of discrimination interact, moving beyond single-attribute analysis to understand complex patterns across overlapping demographic categories.

Units

Unit 1

Unit 1: Historical Patterns of Discrimination in Technology

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How have technologies throughout history reflected, reinforced, and sometimes challenged existing social hierarchies and discriminatory patterns?

- Question 2: What recurring mechanisms enable bias to persist across technological transitions, from mechanical systems to computerization to contemporary AI?

Conceptual Context

Understanding historical patterns of discrimination in technology is foundational to addressing fairness in AI systems. Far from being novel phenomena, the biases we observe in machine learning applications today often represent technological continuations of long-established discriminatory patterns. As Crawford (2021) notes in her analysis of AI systems, "the past is prologue" — historical arrangements of power and privilege become encoded in our technological infrastructure, creating what she terms "political machines" rather than neutral tools.

This historical perspective is essential because it shifts your focus from treating algorithmic bias as merely a technical problem requiring technical solutions to recognizing it as a sociotechnical phenomenon with deep historical roots. When you understand how technologies have consistently reflected and often amplified existing social hierarchies, you develop a more comprehensive framework for identifying potential fairness issues before they manifest in deployed systems.

This Unit builds the cornerstone for subsequent analysis in this Part and the broader Sprint. By examining recurring patterns of technological discrimination, you establish historical templates that inform data representation analysis in Unit 2, provide context for ethical frameworks in Unit 3, and create comparative foundations for analyzing modern manifestations in Unit 4. These insights will directly contribute to the Historical Context Assessment Tool you'll develop in Unit 5, enabling systematic identification of relevant historical patterns for specific AI applications.

2. Key Concepts

Technological Continuity of Discriminatory Patterns

Technologies throughout history have consistently reflected and often reinforced existing social hierarchies rather than disrupting them. This concept is crucial for AI fairness because it helps you recognize that algorithmic bias represents a technological evolution of historical discrimination patterns rather than a novel phenomenon. By identifying these continuities, you can anticipate potential fairness issues in AI systems based on historical precedents.

This concept connects to other fairness concepts by establishing historical templates that inform data representation politics, problem formulation choices, and evaluation criteria. Understanding these historical continuities provides the foundation for identifying which applications require particular scrutiny based on their connection to domains with established discrimination patterns.

Historian of technology Mar (2016) demonstrates this continuity by tracing how telephone technologies in the early 20th century maintained social stratification through differential access. Despite the telephone's technical potential to democratize communication, economic and social barriers resulted in telephone networks that primarily connected privileged communities while excluding marginalized populations. The tiered service model—with party lines for lower-income communities and private lines for wealthier areas—functionally extended existing social hierarchies into the new technological infrastructure.

This pattern persists in contemporary digital technologies. For instance, Eubanks (2018) documents how welfare administration systems automate and intensify existing patterns of surveillance and punishment directed at economically marginalized communities. These systems subject benefit recipients to intensive data collection, algorithmic assessment, and automated decision-making in ways that echo historical patterns of control over these populations.

For the Historical Context Assessment Tool you'll develop, understanding technological continuity enables you to systematically identify relevant historical patterns for specific AI applications. By recognizing these continuities, you can anticipate which historical patterns might manifest in particular technological contexts, focusing fairness assessments on the most relevant historical precedents.

Encoded Social Categories and Classification Systems

Technologies encode social classifications that reflect specific historical and political contexts rather than objective or natural categories. This concept is fundamental to AI fairness because machine learning systems inevitably inherit and sometimes amplify these historically contingent classification schemes through their training data and problem formulations.

This concept interacts with data representation by highlighting how seemingly technical classification decisions embody specific historical perspectives. It connects to fairness metrics by demonstrating why certain attributes become protected categories requiring particular attention in fairness evaluations.

Bowker and Star's (1999) influential analysis of classification systems demonstrates how medical diagnostic categories evolved through complex social and political processes rather than simply reflecting natural biological distinctions. Their research shows how the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) has shifted dramatically over time, as categories emerged from negotiations between medical, insurance, and government stakeholders rather than from objective scientific discovery alone.

In AI systems, these historical classification decisions become encoded through training data. For example, facial analysis technologies often employ binary gender classification (male/female) that erases non-binary and transgender identities. When datasets like Labeled Faces in the Wild (LFW) contain these binary classifications, the machine learning systems trained on them inevitably reproduce and sometimes amplify this categorical erasure (Keyes, 2018).

For the Historical Context Assessment Tool, understanding encoded social categories helps you identify how historical classification systems might influence contemporary AI applications. By recognizing the historical contingency of classifications used in training data, problem formulations, and evaluation metrics, you can better assess which aspects of an AI system might reproduce problematic categorization patterns.

Technology's Role in Social Stratification

Technologies have historically functioned as mechanisms for maintaining or challenging existing social hierarchies, often determining who benefits from technological advances and who bears their burdens. This concept is essential for AI fairness because it helps you recognize how AI systems may similarly maintain or amplify social stratification when deployed in contexts with existing power imbalances.

This concept connects to fairness evaluation by highlighting the importance of examining not just technical performance but also social impact. It interacts with fairness metrics by demonstrating why disaggregated analysis across social groups is essential for understanding differential effects.

Noble's (2018) research on search engine algorithms demonstrates how these technologies often reinforce existing racial and gender stereotypes. Her analysis of Google search results shows how algorithms could return dehumanizing and sexualized results for searches related to Black women, effectively amplifying existing patterns of marginalization. Noble terms this phenomenon "technological redlining," drawing an explicit connection to historical housing discrimination practices.

Similarly, Benjamin (2019) documents how facial recognition technologies consistently perform worse on darker-skinned faces, particularly for women, creating what she terms a "New Jim Code" that extends historical patterns of racial discrimination into the algorithmic era. These technologies don't merely reflect existing social hierarchies but actively intensify them by subjecting certain populations to higher error rates and their negative consequences.

For the Historical Context Assessment Tool, understanding technology's role in social stratification helps you identify which applications present the highest risk of perpetuating or amplifying existing hierarchies. By examining historical precedents of how technologies have affected social stratification, you can better assess which contemporary AI applications require particularly careful fairness evaluation.

Selective Optimization in Technical Development

Throughout history, technologies have been selectively optimized for the needs, bodies, and contexts of dominant groups, creating systematic performance disparities when applied to marginalized populations. This concept is critical for AI fairness because machine learning systems similarly learn to optimize for majority patterns represented in training data, potentially creating performance disparities across demographic groups.

This concept interacts with fairness metrics by highlighting why simply optimizing for overall accuracy can perpetuate historical disparities. It connects to data representation by demonstrating how certain populations become "edge cases" due to their underrepresentation in the development process.

Criado Perez (2019) documents how supposedly "universal" technologies from automotive safety features to medical devices have historically been designed primarily for male bodies, creating potentially dangerous performance disparities for women. For instance, crash test dummies based on male physiology led to seatbelt and airbag designs that provided less protection for the average woman, leading to higher injury rates in accidents.

In AI systems, similar optimization patterns emerge when facial recognition technologies are primarily developed and tested on lighter-skinned male faces. Buolamwini and Gebru's (2018) landmark "Gender Shades" study demonstrated that commercial facial analysis technologies exhibited error rate disparities of up to 34.4% between light-skinned men and dark-skinned women, reflecting the selective optimization of these systems for majority groups.

For the Historical Context Assessment Tool, understanding selective optimization helps you identify potential performance disparities in AI applications based on historical precedents. By recognizing which populations have historically been treated as "edge cases" in specific domains, you can better assess which groups might experience similar marginalization in contemporary AI systems.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, historical patterns of discrimination map to specific components of ML systems:

- Problem Formulation: Historical problems and priorities influence which issues are deemed worthy of technological intervention and how success is defined.

- Data Collection: Historical sampling biases shape who is represented in datasets and what attributes are measured.

- Feature Engineering: Historical classification systems determine how variables are defined and encoded.

- Model Selection: Historical performance expectations influence which algorithms are selected and how they're configured.

- Evaluation Metrics: Historical values determine which outcomes are prioritized and which disparities are deemed acceptable.

This domain mapping helps you understand how historical patterns manifest at different stages of the ML lifecycle rather than treating bias as a generic technical issue. The Historical Context Assessment Tool will incorporate this mapping to identify stage-specific risks based on relevant historical patterns.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract historical concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Technological continuity of discrimination functions like architectural inheritance in cities—just as modern buildings are constructed on foundations laid by previous generations, creating structural continuities despite surface-level changes, new technologies build upon existing social infrastructures. Even when their interfaces change dramatically, they often preserve and sometimes intensify historical patterns of access and exclusion. This helps explain why technologies that appear radically new often reproduce familiar patterns of discrimination.

- Encoded social categories operate like measurement systems—just as the choice between metric and imperial units represents specific historical contexts rather than natural distinctions, social classification systems reflect particular historical perspectives rather than objective realities. When technologies adopt these classification systems, they inevitably inherit the historical perspectives embedded within them. This explains why seemingly technical decisions about categories can have profound fairness implications.

- Technology's role in social stratification resembles how transportation infrastructure shapes city development—just as highway placement decisions in mid-20th century American cities often reinforced residential segregation by cutting through Black neighborhoods while connecting white suburbs, technological infrastructure can either reinforce or challenge existing social boundaries. This helps you recognize why the deployment context of AI systems significantly influences their fairness implications.

Intersectionality Consideration

Historical patterns of discrimination have never operated along single identity dimensions but through complex interactions between multiple forms of marginalization. Crenshaw's (1989) foundational work on intersectionality demonstrates that analyzing discrimination along single axes (e.g., only race or only gender) fails to capture unique forms of marginalization experienced at their intersections.

For technologies, this means discrimination patterns often manifest differently across intersectional identities. For example, Benjamin (2019) notes that facial recognition technologies typically perform worst on darker-skinned women—a pattern that wouldn't be captured by examining either racial or gender disparities in isolation.

The Historical Context Assessment Tool must explicitly incorporate intersectional analysis by:

- Examining historical patterns across multiple dimensions simultaneously rather than treating each protected attribute in isolation;

- Identifying unique discrimination mechanisms that operate at demographic intersections;

- Recognizing how multiple forms of marginalization interact to create distinct technological experiences.

By incorporating these intersectional considerations, the tool will enable more comprehensive identification of relevant historical patterns, avoiding the analytical blindspots that occur when examining protected attributes independently.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To systematically analyze historical patterns of discrimination in technology, follow this structured methodology:

-

Historical Pattern Identification

-

Examine historical discrimination in the specific domain where the AI system will be deployed (e.g., healthcare, criminal justice, hiring).

- Research how previous technologies in this domain have reflected, reinforced, or challenged existing social hierarchies.

-

Identify recurring mechanisms through which bias has persisted across technological transitions in this domain.

-

Pattern-to-Risk Mapping

-

Map identified historical patterns to specific components of the ML system under consideration.

- Determine how historical classification systems might influence feature definitions and encodings.

- Assess how historical performance disparities might manifest in model accuracy across groups.

-

Analyze how historical optimization priorities might shape evaluation metrics and thresholds.

-

Prioritization Framework

-

Assess the strength of the historical connection between identified patterns and the current application.

- Evaluate the potential harm if historical patterns were to recur in the current system.

- Determine the visibility of potential bias (some forms are more readily apparent than others).

- Prioritize which historical patterns require particular attention in subsequent fairness assessments.

These methodologies should integrate with standard ML workflows by informing initial risk assessment during problem formulation, guiding data collection and feature engineering decisions, and establishing evaluation criteria that account for historical disparities.

Implementation Challenges

When implementing historical analysis in AI fairness assessments, practitioners commonly face these challenges:

-

Limited Historical Knowledge: Most data scientists lack deep historical knowledge about discrimination patterns in specific domains. Address this by:

-

Collaborating with domain experts who understand the historical context.

- Creating accessible resources summarizing key historical patterns for commonly used applications.

-

Developing standard templates that guide non-historians through the essential questions.

-

Communicating Historical Relevance to Technical Teams: Teams may resist historical analysis as irrelevant to technical implementation. Address this by:

-

Framing historical patterns as risk factors that directly impact system performance.

- Providing concrete examples where historical understanding prevented fairness issues.

- Developing visualizations that explicitly connect historical patterns to system components.

Successfully implementing historical analysis requires resources including time for research, access to domain experts, and educational materials that make historical patterns accessible to technical practitioners without extensive background knowledge.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your historical analysis is effective, implement these evaluation strategies:

-

Coverage Assessment:

-

Verify that the analysis examines multiple historical periods, not just recent precedents.

- Ensure assessment covers various discrimination mechanisms, not just the most obvious forms.

-

Confirm the analysis addresses intersectional considerations rather than treating protected attributes in isolation.

-

Connection Verification:

-

Evaluate whether identified historical patterns have clear connections to the current application.

- Verify that mapped risks are specific to system components rather than general concerns.

-

Assess whether prioritization decisions are justified by evidence rather than assumptions.

-

Actionability Check:

-

Determine whether the analysis produces actionable insights for subsequent fairness work.

- Verify that identified historical patterns inform concrete assessment approaches.

- Ensure the analysis suggests specific monitoring metrics based on historical patterns.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated with your organization's fairness governance process, providing a systematic way to verify that historical context has been appropriately considered in the AI development process.

4. Case Study: Criminal Risk Assessment Systems

Scenario Context

A government agency is developing a machine learning-based risk assessment system to predict recidivism risk for individuals awaiting trial, with predictions informing pre-trial detention decisions. Stakeholders include the judicial system seeking efficiency, defendants whose liberty is at stake, communities affected by crime and incarceration, and government officials concerned with both public safety and system fairness.

This scenario presents significant fairness challenges due to the domain's extensive history of racial discrimination and the high stakes of prediction errors for both individuals and communities.

Problem Analysis

Applying core concepts from this Unit reveals several historical patterns highly relevant to this application:

- Technological Continuity: Historical risk assessment in criminal justice has consistently reflected racial biases in the broader system. Harcourt's (2010) research demonstrates how early 20th century parole prediction instruments—using factors like "family criminality" and neighborhood characteristics—functionally embedded racial discrimination in seemingly objective assessments, creating a precedent for algorithms that predict higher risk for Black defendants.

- Encoded Social Categories: The criminal justice system has historically employed categories that reflect specific power relations rather than objective classifications. For instance, the category of "prior police contact" treats discretionary police attention as an objective measure of criminal tendency—despite extensive evidence that policing has historically focused disproportionately on Black neighborhoods regardless of actual crime rates (Hinton, 2016).

- Technology's Role in Social Stratification: Technologies in criminal justice have historically amplified existing disparities. Ferguson (2017) documents how early data-driven policing technologies directed additional police resources to already over-policed areas, creating feedback loops that intensified racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

- Selective Optimization: Criminal risk assessment tools have historically been optimized for predicting outcomes defined by a system with documented racial biases. Richardson et al. (2019) demonstrate how these tools often predict future arrest (which reflects policing patterns) rather than actual criminal behavior, optimizing for a variable shaped by historical discrimination.

From an intersectional perspective, these patterns manifest differently across demographic intersections. For example, Ritchie (2017) documents how Black women experience unique forms of criminalization that wouldn't be captured by examining either racial or gender disparities in isolation. This suggests the risk assessment system might create distinctive fairness issues for specific intersectional groups.

Solution Implementation

To address these historical patterns, the team implemented a structured historical analysis approach:

- They first conducted comprehensive historical research on criminal risk assessment, examining both academic literature and consulting with criminal justice reform advocates who provided historical context about how similar tools have affected marginalized communities.

-

They developed a detailed mapping between historical discrimination patterns and specific components of the proposed system:

-

Problem formulation: Questioned whether predicting "recidivism" operationalized as re-arrest rather than reconviction reproduces historical policing biases.

- Data collection: Identified that training data reflected historical patterns of over-policing in certain communities.

- Feature selection: Recognized that variables like "prior police contact" and "neighborhood characteristics" have functioned as proxies for race throughout criminal justice history.

-

Evaluation metrics: Determined that optimizing only for overall accuracy would likely reproduce historical disparities.

-

They created a prioritization framework that identified the use of arrest-based outcome measures and neighborhood-based features as highest-risk elements based on their strong historical connection to documented discrimination patterns.

- They implemented an intersectional analysis component that examined how prediction patterns might differ across specific demographic intersections, particularly focusing on how the system might affect Black women differently than other groups.

Throughout implementation, they maintained detailed documentation of identified historical patterns and their connection to specific system components, creating an audit trail that informed subsequent fairness assessments.

Outcomes and Lessons

The historical pattern analysis yielded several critical insights that significantly influenced the system development:

- The team redefined the prediction target from "any re-arrest" to "conviction for a violent offense," reducing the influence of discriminatory policing patterns on the outcome variable.

- They eliminated neighborhood-based features with strong historical connections to redlining and segregation, reducing a major source of proxy discrimination.

- They implemented disaggregated performance evaluation across both broad demographic categories and specific intersections, revealing performance disparities that wouldn't have been apparent in aggregate metrics.

- They developed custom fairness metrics based on the specific historical patterns identified, rather than applying generic fairness definitions.

Key generalizable lessons included:

- Historical analysis is most effective when it produces specific, actionable insights rather than general observations about discrimination.

- Collaboration between technical teams and domain experts with historical knowledge significantly improves the quality of historical pattern identification.

- Explicit documentation of historical patterns creates accountability and ensures historical insights inform the entire development process.

- Intersectional analysis reveals unique fairness concerns that wouldn't be captured by examining protected attributes in isolation.

These insights directly informed the development of the Historical Context Assessment Tool, particularly the need for structured methodologies that connect specific historical patterns to concrete technical components.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Historical Relevance to Technical Implementation

Q: How does historical analysis practically impact technical implementation decisions in machine learning systems?

A: Historical analysis directly informs several critical technical decisions: First, it helps identify high-risk features that have historically functioned as proxies for protected attributes, guiding feature selection and engineering. Second, it informs outcome variable definition by revealing how certain operationalizations may embed historical biases, leading to more careful problem formulation. Third, it guides the selection of appropriate fairness metrics and thresholds based on historical disparities in the domain. Fourth, it informs disaggregated evaluation strategies by identifying which demographic groups and intersections have historically experienced unique discrimination patterns. Rather than a separate "historical analysis" phase, this approach should integrate throughout the technical development process, informing design decisions at each stage.

FAQ 2: Balancing Historical Awareness With Innovation

Q: How can we acknowledge historical discrimination patterns without assuming a new system will necessarily reproduce them?

A: Historical analysis should function as risk assessment rather than deterministic prediction—identifying where bias might emerge without assuming it inevitably will. The goal is targeted vigilance rather than technological pessimism. Practically, you should: (1) Document relevant historical patterns as specific risk factors rather than foregone conclusions; (2) Design targeted testing and evaluation focused on these risk factors; (3) Implement monitoring systems that track whether historical patterns actually emerge in the deployed system; and (4) Create feedback mechanisms that enable continuous improvement based on observed outcomes. This approach treats historical patterns as important warning signs warranting careful attention rather than inescapable constraints, allowing for innovation while maintaining appropriate caution in high-risk domains.

6. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

Throughout this Unit, you've explored how technologies throughout history have reflected, reinforced, and sometimes challenged existing social hierarchies. Key insights include:

- Technological Continuity: Discrimination patterns persist across technological transitions, with new technologies often reproducing and sometimes intensifying historical inequities despite surface-level changes.

- Encoded Social Categories: Technologies inevitably embed classification systems that reflect specific historical and political contexts rather than objective realities.

- Social Stratification: Technologies have historically functioned as mechanisms for maintaining or challenging existing social hierarchies, determining who benefits and who bears burdens.

- Selective Optimization: Technologies are typically optimized for dominant groups, creating systematic performance disparities when applied to marginalized populations.

These concepts directly address our guiding questions by explaining how historical patterns persist in modern systems and identifying the recurring mechanisms that enable this continuity. They provide the essential foundation for the Historical Context Assessment Tool by establishing what patterns to look for and how they typically manifest.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- For each new AI application, research the specific history of technology use and discrimination in that domain rather than relying on generic patterns.

- Examine the categories embedded in your data and question their historical origins rather than treating them as natural or inevitable.

- Consider who has historically benefited from and been harmed by technologies in your application domain, and assess whether your current system might reproduce these patterns.

- Document identified historical patterns specifically enough to inform concrete technical decisions, not just general fairness aspirations.

If you're new to historical analysis in AI, start with well-documented domains like criminal justice, hiring, or healthcare, where extensive research already exists on historical discrimination patterns. Build your analytical capabilities in these areas before tackling domains with less established historical analysis.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we'll build on this historical foundation by examining how social contexts shape data representation. You will learn how classification systems and measurement practices encode power relations, how missing data reflects strategic decisions rather than random omissions, and how data collection practices amplify or mitigate historical biases.

The historical patterns you've learned to identify will directly inform this data representation analysis, helping you recognize how classification decisions in modern datasets might reflect and reproduce historical discrimination patterns. By connecting historical awareness to specific data practices, you'll develop a more comprehensive understanding of how bias enters AI systems through seemingly technical data representation choices.

References

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the new Jim Code. Polity.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991-1013.

Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. MIT Press.

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 77–91).

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139-167.

Criado Perez, C. (2019). Invisible women: Data bias in a world designed for men. Abrams Press.

Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. St. Martin's Press.

Ferguson, A. G. (2017). The rise of big data policing: Surveillance, race, and the future of law enforcement. NYU Press.

Harcourt, B. E. (2010). Against prediction: Profiling, policing, and punishing in an actuarial age. University of Chicago Press.

Hinton, E. (2016). From the war on poverty to the war on crime: The making of mass incarceration in America. Harvard University Press.

Keyes, O. (2018). The misgendering machines: Trans/HCI implications of automatic gender recognition. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 2(CSCW), 1-22.

Mar, S. T. (2016). The mechanics of racial segregation in telecommunication networks. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(8), 1339-1358.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

Richardson, R., Schultz, J. M., & Crawford, K. (2019). Dirty data, bad predictions: How civil rights violations impact police data, predictive policing systems, and justice. New York University Law Review Online, 94, 15-55.

Ritchie, A. J. (2017). Invisible no more: Police violence against Black women and women of color. Beacon Press.

Roberts, D. (2012). Fatal invention: How science, politics, and big business re-create race in the twenty-first century. The New Press.

Unit 2

Unit 2: Data Representation and Social Context

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How do social contexts and power structures influence data representation in ways that can introduce or amplify bias in AI systems?

- Question 2: How can data scientists critically examine the social assumptions embedded in their dataset construction, categorization schemes, and feature representations to create more equitable AI systems?

Conceptual Context

Data representation—how we collect, categorize, and encode information about the world for machine learning systems—lies at the critical intersection of technical implementation and social meaning. While data collection and preparation often appear as purely technical tasks, they fundamentally involve social decisions about what information matters, how identity categories should be defined, and which distinctions are relevant for a particular task.

These representation choices directly influence AI fairness because they determine which aspects of reality become visible or invisible to learning algorithms. As D'Ignazio and Klein (2020) emphasize in their seminal work Data Feminism, data are not neutral reflections of reality but rather constructed artifacts that embed specific perspectives, priorities, and power structures. When these representations encode or amplify existing social inequities, AI systems trained on such data will inevitably reproduce and potentially magnify these patterns (D'Ignazio & Klein, 2020).

This Unit builds directly on the historical foundations established in Unit 1 by examining how historical patterns of discrimination shape contemporary data representation practices. It provides the essential foundation for understanding algorithm design biases in Unit 3 by establishing how social contexts influence the raw material that algorithms process. The insights you develop in this Unit will directly inform the Historical Context Assessment Tool we will develop in Unit 5, particularly in analyzing how social assumptions embedded in data representation connect to historical patterns of discrimination.

2. Key Concepts

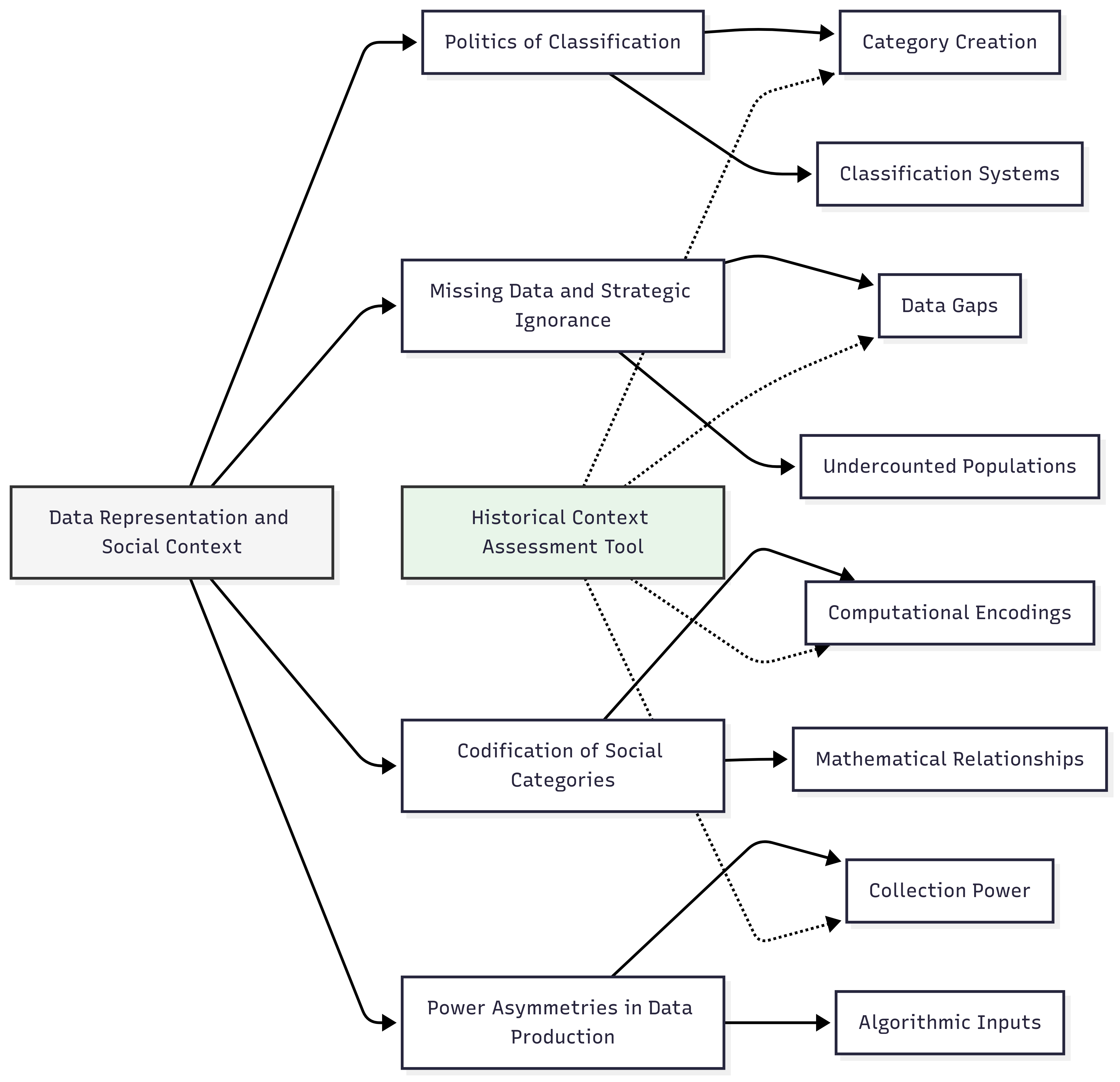

The Politics of Classification

Classification systems—the ways we divide the world into discrete categories—are not neutral technical frameworks but rather social constructs that embed specific historical contexts, power relations, and worldviews. This concept is fundamental to AI fairness because machine learning relies heavily on classifications for both input features and prediction targets, with these classification choices directly shaping what systems can perceive and predict.

Classification connects to other fairness concepts by establishing the fundamental categories that will be used throughout the machine learning pipeline. These initial classification decisions constrain all subsequent fairness interventions, as techniques can only address biases in categories that have been recognized and encoded.

Research by Bowker and Star (1999) demonstrates how classification systems that appear technical or objective actually embed specific sociopolitical assumptions. In their landmark book Sorting Things Out, they examine how medical classification systems like the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) developed through complex political negotiations rather than purely scientific processes, with significant consequences for how health conditions are understood, treated, and funded (Bowker & Star, 1999).

These insights apply directly to AI fairness when considering how protected attribute categories are defined in datasets. For instance, binary gender classifications (male/female) exclude non-binary individuals and reinforce gender as a simple binary rather than a complex social and biological spectrum. Similarly, racial classifications vary dramatically across cultures and historical periods, yet are often treated as fixed, objective categories in machine learning datasets.

For the Historical Context Assessment Tool we will develop, understanding the politics of classification will help identify how historical power structures influence contemporary data categories, revealing potential sources of bias before model development begins. By questioning classification systems rather than accepting them as given, you can identify which social assumptions are being encoded in your data and how these might privilege certain groups over others.

Missing Data and Strategic Ignorance

Missing data in datasets often reflects not just random technical limitations but "strategic ignorance"—systematic patterns of which populations, variables, and phenomena are consistently undercounted or overlooked in data collection. This concept is crucial for AI fairness because these gaps in representation can create invisible biases that standard fairness metrics fail to detect, as they typically only evaluate disparities among groups actually present in the data.

Missing data interacts with classification politics by shaping not just how phenomenon are categorized but whether they are measured at all. Together, these concepts determine which aspects of reality become visible and actionable within AI systems.

D'Ignazio and Klein (2020) illustrate this strategic ignorance through numerous examples, such as the systematic undercounting of maternal mortality in the United States, particularly for Black women. This data gap prevented recognition of a serious public health disparity for decades. Similarly, they highlight how data on sexual harassment and assault were not systematically collected until feminist activists fought for such measurement, demonstrating how power structures influence which problems are deemed worthy of data collection (D'Ignazio & Klein, 2020).

For AI systems, these gaps create significant fairness challenges. For example, Buolamwini and Gebru's (2018) landmark Gender Shades study demonstrated that facial recognition datasets contained dramatically fewer dark-skinned women, leading to higher error rates for this demographic. The absence of comprehensive data made these disparities invisible until specifically tested with a more demographically balanced evaluation set (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018).

For our Historical Context Assessment Tool, understanding strategic ignorance will guide the development of data auditing approaches that look beyond the available data to identify which populations, variables, or contexts might be systematically missing. This approach transforms missing data from an inevitable technical limitation into an actionable fairness consideration with historical roots that can be identified and addressed.

Codification of Social Categories

The process of translating complex social categories into discrete computational representations—often through simplistic encodings like one-hot vectors or numeric scales—involves significant reduction of social complexity. This codification is fundamental to AI fairness because the technical implementation of social categories directly shapes how algorithms perceive and process social differences.

Codification connects directly to classification politics by implementing classification decisions in computational form, often further simplifying already reductive categories. This technical encoding can amplify biases present in classification systems or introduce new distortions through inappropriate mathematical representations.

As Benjamin (2019) demonstrates in her book Race After Technology, the reduction of race to simplistic computational categories fails to capture its social, historical, and contextual complexity. For instance, representing race as a set of mutually exclusive categories (e.g., one-hot encoding) mathematically enforces the problematic assumption that racial categories are clean, discrete, and universal, rather than socially constructed, overlapping, and contextually variable (Benjamin, 2019).

This codification challenge extends beyond protected attributes to proxy variables. Obermeyer et al. (2019) revealed how healthcare algorithms using medical costs as a proxy for medical needs systematically disadvantaged Black patients because the proxy failed to account for historical disparities in healthcare access. The mathematical relationship between the codified proxy (costs) and the intended concept (medical need) varied by race due to systemic inequities, creating significant algorithmic bias (Obermeyer et al., 2019).

For the Historical Context Assessment Tool, analyzing codification practices will help identify how technical implementations of social categories might embed or amplify historical biases. This includes examining not just the explicit encoding of protected attributes but also the mathematical relationships between proxy variables and social categories under various historical conditions.

Power Asymmetries in Data Production

Data production—who collects data, about whom, for what purpose, and under what conditions—involves fundamental power asymmetries that shape resulting datasets. This concept is essential for AI fairness because these asymmetries directly influence which perspectives are represented in training data and how different populations are characterized.

Power asymmetries interact with all previously discussed concepts: they influence which classifications are used, which data are collected or ignored, and how social categories are codified. Together, these interactions create complex patterns of advantage and disadvantage in data representations.

Eubanks (2018) demonstrates in her book Automating Inequality how data about poor and working-class people are disproportionately collected through surveillance and compliance systems rather than voluntary participation. This asymmetry creates datasets where marginalized groups appear primarily as problems to be solved rather than as full persons with agency and diverse experiences, shaping how these populations are represented in resulting models (Eubanks, 2018).

Similarly, research on content moderation datasets has shown that platform workers—often from the Global South—label data according to guidelines developed primarily in Western contexts, creating global datasets that nevertheless embed specific cultural assumptions about appropriate content (Roberts, 2019). This asymmetry between who develops classification schemes and who implements them creates datasets that appear universal but actually privilege particular cultural perspectives.

For our Historical Context Assessment Tool, analyzing power asymmetries in data production will help identify how historical patterns of advantage and disadvantage shape contemporary datasets through collection procedures, annotation processes, and validation practices. By examining who has agency in data production and how this agency is distributed across demographic groups, we can identify potential sources of bias that standard statistical analyses might miss.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, data representation and social context connect to specific components of ML systems:

- Variable Selection: Which phenomena are deemed worth measuring and how these selections reflect social priorities and power structures.

- Feature Engineering: How raw measurements are transformed into features through processes that may embed social assumptions about what constitutes meaningful variation.

- Data Schema Design: How relational structures between data elements encode assumptions about which relationships matter and which can be ignored.

- Encoding Mechanisms: How categorical variables are mathematically represented and what assumptions these encodings make about category relationships.

- Metadata Frameworks: What contextual information about data collection is preserved or discarded and how this shapes interpretation.

This domain mapping helps you understand how social contexts influence specific technical components of ML systems rather than viewing bias as a generic problem. The Historical Context Assessment Tool will incorporate this mapping to help practitioners identify where and how historical patterns of discrimination might manifest in their data representations.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Classification systems function like maps that highlight certain features of terrain while necessarily omitting others. Just as mapmakers must decide which elements of geography to include and how to represent them—decisions shaped by their purpose, perspective, and historical context—data scientists select which aspects of complex social reality to encode as discrete categories. Neither maps nor classification systems are neutral representations of objective reality; both reflect specific priorities and perspectives that determine what becomes visible or invisible.

- Strategic ignorance in data collection resembles a grocery store inventory system that meticulously tracks certain products while completely ignoring others. If the inventory system carefully counts packaged foods but doesn't track fresh produce at all, analytics based on this data would provide a distorted view of overall sales patterns and customer preferences. Similarly, when data collection systematically overlooks certain populations or variables, analyses based on these incomplete datasets create distorted representations that make some issues invisible.

- Power asymmetries in data production can be understood through the analogy of restaurant reviews. When only food critics write reviews, we get a particular perspective focused on specific aspects of dining (perhaps sophisticated flavors and presentation) while missing others (like value for money or family-friendliness). Similarly, when data about marginalized communities are primarily collected by outsiders for compliance or surveillance purposes, those datasets capture particular aspects of these communities (often focused on problems) while missing others (like community strengths and internal diversity).

Intersectionality Consideration

Data representation practices present unique challenges for intersectional fairness, where multiple aspects of identity interact to create distinct experiences that cannot be understood by examining each dimension independently. Traditional data structures often flatten these intersectional experiences through simplistic, single-attribute categorizations or independent treatment of identity dimensions.

For example, analysis by Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) demonstrated that facial recognition accuracy for darker-skinned women was substantially lower than what would be predicted by examining either gender or skin tone effects independently. This intersectional effect revealed distinct patterns that would remain invisible if examining demographic disparities along single dimensions (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018).

Similarly, Crenshaw's (1989) foundational work on intersectionality examined how employment discrimination against Black women created unique patterns that were not captured by analyzing either racial discrimination or gender discrimination in isolation. Data representation schemes that treat protected attributes as independent variables can systematically obscure these intersectional patterns (Crenshaw, 1989).

For the Historical Context Assessment Tool, addressing intersectionality in data representation requires:

- Examining how classification systems might erase or distort intersectional identities by forcing individuals into mutually exclusive categories;

- Identifying which intersectional populations might be systematically missing or undercounted in datasets;

- Analyzing how power asymmetries in data production might particularly disadvantage individuals at specific intersections; and

- Evaluating whether codification practices preserve or erase the unique patterns that emerge at demographic intersections.

By explicitly incorporating these intersectional considerations, the tool will help identify subtle representational biases that might otherwise remain undetected.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To systematically examine social contexts in data representation, implement this structured methodology:

-

Classification Audit:

-

Document all classification systems used in your dataset, including protected attributes and potential proxies.

- Research the historical development of these classification systems to identify potential embedded biases.

- Evaluate whether classifications capture the full diversity of the relevant population or artificially constrain representation.

-

Analyze whether classification boundaries reflect meaningful distinctions for your task or arbitrary divisions with historical baggage.

-

Representation Gap Analysis:

-

Compare dataset demographics to relevant population benchmarks to identify underrepresented groups.

- Document variables that might be systematically missing for certain populations.

- Examine whether proxy variables have consistent meaning across demographic groups.

-

Identify potential "data deserts" where information is systematically sparse due to historical collection patterns.

-

Codification Evaluation:

-

Analyze how social categories are mathematically encoded and what assumptions these encodings embed.

- Test whether distance metrics in feature space reflect meaningful similarities or arbitrary technical choices.

- Evaluate whether technical implementations preserve important social nuances or flatten complex identities.

-

Document potential information loss in the translation from social categories to computational representations.

-

Power Analysis in Data Lifecycle:

-

Document who designed the data schema and whether diverse perspectives informed these decisions.

- Analyze who collected the data and under what conditions (mandatory compliance, voluntary participation, etc.).

- Evaluate who labeled or annotated the data and what guidelines shaped these interpretations.

- Assess who validates data quality and what metrics they use to determine representativeness.

These methodologies should integrate with standard ML workflows by extending exploratory data analysis to explicitly incorporate critical social analysis. While adding complexity to data preparation, these approaches help identify potential fairness issues before they become encoded in model behavior.

Implementation Challenges

When implementing these analytical approaches, practitioners commonly face these challenges:

-

Limited Historical and Social Context Knowledge: Many data scientists lack background knowledge about the historical development of classification systems or social contexts of data production. Address this by:

-

Collaborating with domain experts from relevant social science fields;

- Researching the historical development of key classifications used in your dataset; and

-

Documenting assumptions and limitations in your understanding of social contexts.

-

Communicating Social Representation Issues in Technical Environments: Technical teams may resist considerations they view as "political" rather than technical. Address this by:

-

Framing representation issues in terms of concrete technical consequences for model performance;

- Providing specific examples where social context analysis identified issues that affected system accuracy or reliability; and

- Developing clear visualizations that illustrate representation disparities and their potential impacts.

Successfully implementing these approaches requires resources including time for deeper analysis beyond standard data profiling, access to relevant literature on social classification systems, and ideally collaboration with experts in relevant domains who can provide historical and social context for representation practices.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your analysis of data representation and social context is effective, implement these evaluation strategies:

-

Representation Completeness Assessment:

-

Calculate coverage metrics showing what percentage of relevant social variation is captured in your classification systems.

- Establish minimum thresholds for representation across demographic groups and intersections.

-

Document limitations in classification systems and their potential impacts on model performance.

-

Context Documentation Review:

-

Develop a rubric for evaluating the completeness of social context documentation.

- Assess whether documentation enables new team members to understand the historical and social background of key data representations.

-

Verify that limitations and assumptions about social categories are explicitly documented.

-

Stakeholder Validation:

-

Engage representatives from relevant communities to review representation choices.

- Document feedback on whether classifications and encodings respect community self-understanding.

- Implement revision processes when representation issues are identified.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated with your organization's broader data governance framework, providing structured assessments of representation quality alongside more traditional data quality metrics.

4. Case Study: Health Risk Assessment Algorithm

Scenario Context

A healthcare company is developing a machine learning system to identify patients who would benefit from enhanced care management programs. The algorithm will analyze patient records to predict future healthcare needs and assign risk scores that determine resource allocation. Key stakeholders include healthcare providers seeking efficient resource allocation, patients who would benefit from additional services, insurance companies concerned with costs, and regulators monitoring healthcare equity.

Fairness is particularly critical in this domain due to historical disparities in healthcare access, outcomes, and representation in medical data. The system will directly impact which patients receive additional resources, making representation fairness both an ethical and legal requirement under healthcare regulations.

Problem Analysis

Applying core concepts from this Unit reveals several potential representation issues in the healthcare risk assessment scenario:

- Classification Politics: The medical classification systems used in the dataset (ICD-10 codes, procedure codes, etc.) developed through complex historical processes that embed particular understandings of health and disease. Analysis reveals that certain conditions affecting different demographic groups have different historical patterns of recognition and codification. For example, conditions primarily affecting women historically received less research attention and have less granular classification than comparable conditions affecting men.

- Missing Data and Strategic Ignorance: Examination of the dataset reveals systematic patterns in missing data that correspond to historical healthcare access disparities. Patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have fewer preventive care visits documented, creating a pattern where their health issues often appear only when more severe. Similarly, certain racial and ethnic groups show different patterns of diagnosis that reflect access barriers rather than underlying health differences.

- Codification of Social Categories: The dataset encodes race and ethnicity using outdated classification systems that do not align with contemporary understanding or patient self-identification. Additionally, socioeconomic factors are represented through simplistic proxies like ZIP code, which flatten complex patterns of advantage and disadvantage into single variables with inconsistent meanings across geographic contexts.

- Power Asymmetries in Data Production: The electronic health record data were primarily collected by healthcare professionals rather than reflecting patient experiences directly. Documentation practices vary systematically across clinical settings that serve different demographic populations, with more detailed documentation in well-resourced facilities serving advantaged populations.

From an intersectional perspective, the dataset shows particularly complex patterns at the intersections of race, gender, and socioeconomic status. For example, the medical records of lower-income women of color show distinct documentation patterns that differ from what would be predicted by examining these factors independently.

Solution Implementation

To address these identified representation issues, the team implemented a structured approach:

-

For Classification Politics, they:

-

Collaborated with medical anthropologists to understand the historical development of relevant medical classifications;

- Identified conditions with historically biased classification and developed more balanced feature representations; and

-

Created composite features that captured health needs through multiple complementary classification systems.

-

For Missing Data and Strategic Ignorance, they:

-

Implemented statistical methods to identify and address systematic patterns in missing data;

- Developed features that explicitly captured data sparsity patterns rather than treating them as random; and

-

Created synthetic data approaches to test model sensitivity to historically underrepresented patterns.

-

For Codification of Social Categories, they:

-

Updated demographic category encodings to align with contemporary understanding and patient self-identification;

- Replaced ZIP code with more granular community-level indicators of resource access; and

-

Implemented more nuanced encodings of social determinants of health rather than simplistic proxies.

-

For Power Asymmetries in Data Production, they:

-

Incorporated patient-reported outcomes alongside clinical documentation to balance perspectives;

- Adjusted for documentation thoroughness across different clinical settings; and

- Developed features sensitive to different communication patterns between providers and patients from different backgrounds.

Throughout implementation, they maintained explicit focus on intersectional effects, ensuring that their representation improvements addressed the specific challenges faced by patients at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities.

Outcomes and Lessons

The implementation resulted in significant improvements across multiple dimensions:

- The revised algorithm showed a 45% reduction in racial disparities in resource allocation compared to the original approach.

- Previously invisible health needs in underrepresented populations became detectable through improved representation.

- The model maintained strong overall predictive performance while achieving more equitable outcomes.

Key challenges remained, including ongoing data gaps for some population subgroups and the inherent limitations of working with historically biased medical data.

The most generalizable lessons included:

- The critical importance of examining historical contexts behind medical classification systems, revealing how seemingly objective disease codes actually embed specific historical perspectives and priorities.

- The significant impact of making systematic data gaps explicit rather than treating missing data as random, enabling the model to account for these patterns rather than propagating them.

- The value of incorporating multiple perspectives in data representation, balancing provider documentation with patient-reported experiences to create more comprehensive health profiles.

These insights directly informed the development of the Historical Context Assessment Tool, particularly in creating domain-specific questions that help identify how historical patterns shape contemporary data representations across sectors.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Balancing Critical Analysis With Practical Implementation

Q: How can I incorporate critical analysis of data representation into practical ML workflows without dramatically increasing development time or creating analysis paralysis?

A: Start by incorporating targeted social context questions into existing data profiling workflows rather than creating entirely separate processes. Develop reusable templates for examining classification systems, representation gaps, codification choices, and power dynamics that can be efficiently applied across projects. Focus initial analysis on high-impact features and protected attributes, then expand as resources allow. Create documentation templates that make insights from this analysis clearly actionable for technical implementation. Most importantly, frame this analysis not as an additional burden but as an essential quality check that improves model performance and reduces downstream risks, similar to how security analysis is now integrated into development rather than treated as optional.

FAQ 2: Addressing Representation Issues With Limited Data Access

Q: What approaches can I use when working with datasets where I cannot modify the underlying representation choices or access additional data to address identified gaps?

A: When constrained by fixed datasets, focus on transparency, modeling choices, and careful interpretation. First, document the identified representation limitations and their potential impacts on model performance across groups, making these constraints explicit to stakeholders. Second, implement modeling approaches that account for known representational biases, such as reweighting techniques, fairness constraints, or specialized architectures that are robust to specific representation issues. Third, develop appropriate confidence intervals or uncertainty metrics that reflect data quality differences across groups. Finally, design decision processes that incorporate these limitations—for instance, by implementing higher manual review thresholds for predictions affecting underrepresented groups or adjusting decision thresholds to account for known representation disparities.

6. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

Data representation is not a neutral technical process but rather a social practice that embeds specific historical contexts, power relations, and worldviews. The key concepts from this Unit include:

- Classification politics reveals how apparently objective categorization systems actually embed specific social and historical perspectives that can perpetuate historical inequities.

- Strategic ignorance in data collection creates systematic patterns of missing data that reflect and potentially reinforce historical power structures.

- Codification practices translate complex social categories into computational representations through processes that often flatten social complexity and embed problematic assumptions.

- Power asymmetries in data production influence which perspectives shape datasets and how different populations are represented.