Context

Translating abstract fairness notions into precise, implementable definitions is essential for effective AI system evaluation. Without clear definitions, fairness remains aspirational but unmeasurable, making systematic improvement impossible.

Different fairness definitions embody distinct philosophical perspectives. Egalitarian views emphasizing equal outcomes align with demographic parity, while libertarian perspectives prioritizing procedural fairness align with individual fairness definitions. These philosophical commitments shape technical systems through fairness metric choices.

Mathematical formulations transform philosophical principles into statistical criteria for empirical evaluation. Group fairness definitions ensure similar outcomes across protected groups, individual fairness ensures similar individuals receive similar treatment, and counterfactual fairness examines how predictions would change if protected attributes differed. These implementation choices determine real-world outcomes—who receives loans, housing, or employment opportunities.

Legal frameworks further shape fairness requirements. U.S. anti-discrimination law distinguishes between disparate treatment and disparate impact, while EU regulations emphasize data protection and transparency. These frameworks create compliance requirements that fairness definitions must address in regulated domains.

Critically, mathematical impossibility results prevent simultaneously satisfying multiple fairness criteria. This necessitates explicit trade-offs based on application context and ethical priorities rather than pursuing contradictory objectives.

The Fairness Definition Selection Tool you'll develop in Unit 5 represents the second component of the Fairness Audit Playbook (Sprint Project). This tool will help you systematically select appropriate fairness definitions based on application context, ethical principles, and legal requirements, ensuring assessments address the most relevant dimensions for specific applications.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this Part, you will be able to:

- Analyze philosophical foundations of different fairness definitions. You will evaluate how fairness definitions embody distinct philosophical perspectives on justice and equality, recognizing implicit values embedded in technical definitions rather than treating them as neutral mathematical formulations.

- Implement mathematical formulations of various fairness criteria. You will translate abstract fairness concepts into precise mathematical definitions that can be quantitatively measured in AI systems, moving beyond vague aspirations to specific, calculable criteria.

- Evaluate legal and regulatory implications of fairness definitions. You will assess how fairness definitions align with legal standards across jurisdictions and application domains, selecting definitions that satisfy relevant requirements while understanding where legal and technical approaches diverge.

- Navigate trade-offs between competing fairness definitions. You will analyze inherent tensions between fairness criteria, including mathematical impossibility results that prevent simultaneously optimizing multiple definitions, making informed choices between competing fairness goals.

- Develop contextual approaches to fairness definition selection. You will create methodologies for selecting appropriate fairness definitions based on application domain, stakeholder requirements, and ethical considerations, moving beyond one-size-fits-all approaches.

Units

Unit 1

Unit 1: Conceptual Foundations of Fairness

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: What does "fairness" actually mean in the context of algorithmic systems, and why do different stakeholders often have fundamentally different conceptions of what constitutes a fair outcome?

- Question 2: How can abstract philosophical notions of fairness be translated into precise mathematical formulations that can guide the development of fair AI systems?

Conceptual Context

Understanding the conceptual foundations of fairness is essential for developing AI systems that align with our ethical values and societal expectations. Without a clear grasp of what fairness means in different contexts, any technical implementation will be built on an unstable foundation. This challenge is particularly acute because fairness is not a monolithic concept but rather a multi-faceted one with numerous, sometimes contradictory, interpretations.

As a data scientist or ML engineer, you routinely make decisions that implicitly encode specific fairness assumptions into your systems. These decisions range from how you frame the problem to which metrics you optimize for, and they have real consequences for the people affected by your models. The field of algorithmic fairness has demonstrated that seemingly technical choices about model design often embed normative judgments about what constitutes equitable treatment (Barocas, Hardt, & Narayanan, 2020).

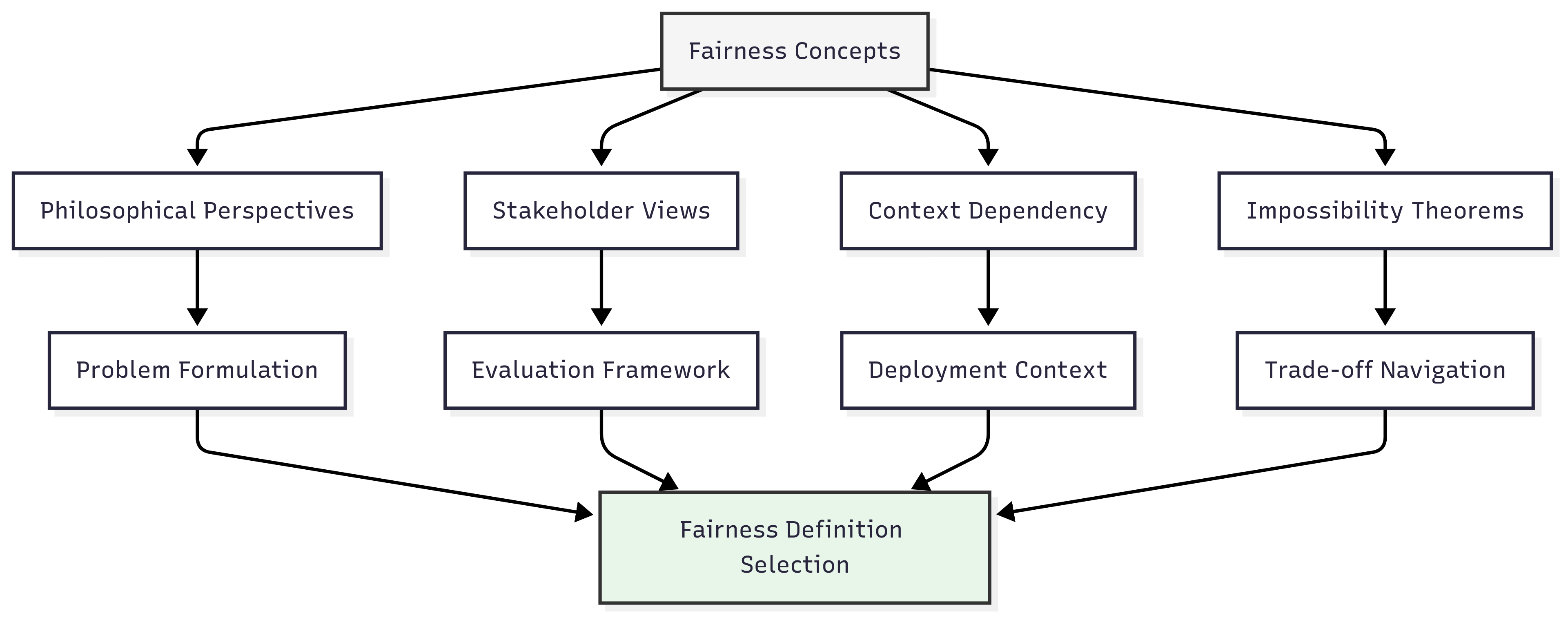

This Unit builds on the historical patterns of discrimination explored earlier in the Sprint and provides the conceptual framework needed for the mathematical formulations of fairness you'll examine in the next Unit. The conceptual understanding you develop here will directly inform the Fairness Definition Selection Tool we will build in Unit 5, particularly in determining which fairness definitions are appropriate for specific contexts based on their underlying philosophical foundations.

2. Key Concepts

Philosophical Perspectives on Fairness

Fairness in AI systems derives from broader philosophical traditions that have developed over centuries. These philosophical frameworks offer different lenses through which to view what constitutes equitable treatment, and they often lead to divergent technical implementations in AI systems.

Understanding these philosophical foundations is essential because they shape how we define and measure fairness in computational contexts. Each philosophical perspective emphasizes different aspects of fairness, leading to distinct mathematical formulations and intervention approaches. Recognizing these differences helps explain why stakeholders may disagree about whether a system is "fair" despite looking at the same technical metrics.

Key philosophical perspectives include:

- Egalitarianism emphasizes equality of outcomes across groups, suggesting that fair AI systems should produce similar results for different demographic groups regardless of other factors. This perspective often manifests in statistical parity metrics that compare prediction rates across protected groups.

- Libertarianism focuses on procedural fairness and treatment of individuals based on relevant factors, suggesting that fair AI systems should make similar predictions for similar individuals regardless of protected attributes. This aligns with individual fairness metrics that emphasize consistency of treatment.

- Rawlsian justice prioritizes improving outcomes for the least advantaged groups, suggesting that fair AI systems should optimize for minimum harm to the most vulnerable populations. This might manifest in metrics that minimize maximum disparity or that prioritize improvements for disadvantaged groups.

- Utilitarianism emphasizes maximizing overall welfare, suggesting that fair AI systems should optimize for aggregate metrics while potentially accepting some disparities if they lead to better overall outcomes. This perspective often prioritizes accuracy or utility metrics alongside fairness constraints.

Binns (2018) demonstrates in his analysis of fairness definitions that these philosophical traditions directly inform how fairness is operationalized in ML systems. For example, demographic parity (equal prediction rates across groups) aligns with egalitarian perspectives, while equal opportunity (equal true positive rates) reflects a more meritocratic view that emphasizes treatment of "qualified" individuals (Binns, 2018).

For the Fairness Definition Selection Tool we'll develop in Unit 5, understanding these philosophical perspectives will be essential for mapping stakeholder values and domain-specific requirements to appropriate fairness definitions. Rather than assuming a universal definition of fairness, the framework will help you select definitions that align with the specific philosophical perspectives most relevant to your application context.

Stakeholder Perspectives and Conflicting Goals

Fairness in AI systems involves multiple stakeholders with potentially conflicting goals and perspectives on what constitutes fair treatment. These stakeholders include system developers, users, individuals subject to algorithmic decisions, regulatory bodies, and broader society. Each may prioritize different aspects of fairness and may evaluate system performance through different normative lenses.

This concept interacts with philosophical perspectives by showing how abstract principles take concrete form in specific contexts with real stakeholders. The plurality of legitimate stakeholder perspectives explains why fairness cannot be reduced to a single universal metric.

Mitchell et al. (2021) illustrate this through their analysis of the COMPAS recidivism prediction tool, where different stakeholder groups (defendants, judges, prosecutors, society at large) had fundamentally different conceptions of fairness. Defendants might prioritize equal false positive rates across groups (minimizing unfair detentions), while prosecutors might emphasize equal false negative rates (minimizing unfair releases). Society broadly might care about long-term impacts on recidivism rates and community well-being. No single fairness metric could satisfy all these legitimate concerns simultaneously (Mitchell et al., 2021).

For our Fairness Definition Selection Tool, understanding stakeholder perspectives will guide the development of a methodology for stakeholder analysis that identifies relevant perspectives, maps their concerns to specific fairness definitions, and provides approaches for navigating conflicting priorities. This ensures that fairness implementations address the concerns of those most affected by system decisions rather than defaulting to technically convenient metrics.

Fairness as Context-Dependent

Fairness is inherently context-dependent, with appropriate definitions varying based on domain-specific factors, cultural contexts, historical patterns, and specific applications. This concept is crucial because it highlights that no single fairness definition is universally applicable across all AI systems. Instead, fairness must be tailored to the specific context in which a system operates.

This concept interacts with both philosophical perspectives and stakeholder analysis by showing how abstract principles and stakeholder concerns manifest differently across contexts. What might be considered fair in one domain could be inappropriate in another due to different historical patterns, social norms, or legal requirements.

Selbst et al. (2019) provide a compelling example in their research on "abstraction traps" in fair ML. They demonstrate how fairness implementations fail when they abstract away critical social and historical contexts. For instance, a "fair" hiring algorithm in the United States might require different considerations than one in India due to different historical discrimination patterns, legal frameworks, and social norms around protected attributes. Similarly, fairness in healthcare prediction has different requirements than fairness in criminal justice due to domain-specific factors like appropriate ground truth definitions and consequence asymmetries (Selbst et al., 2019).

For our Fairness Definition Selection Tool, this context dependency necessitates developing a structured approach for analyzing application domains to identify relevant historical patterns, legal requirements, domain-specific considerations, and cultural factors that should inform fairness definition selection. This ensures that fairness implementations respond to the specific challenges of each application context rather than applying one-size-fits-all solutions.

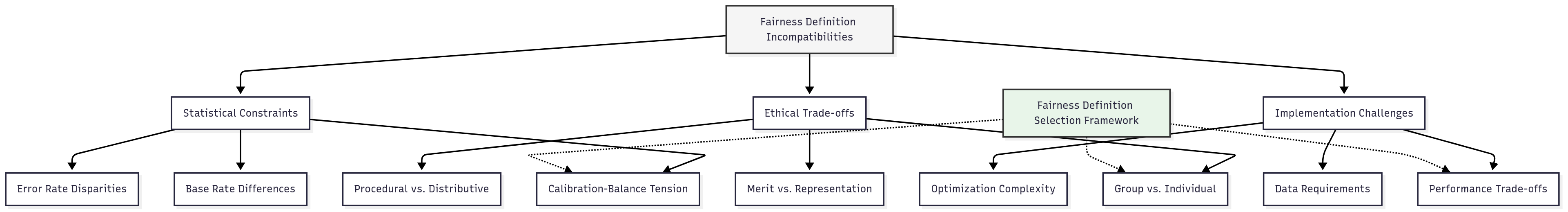

Impossibility Theorems and Inherent Trade-offs

Mathematical impossibility theorems in fairness demonstrate that multiple desirable fairness criteria cannot be simultaneously satisfied in most real-world scenarios. These formal results establish inherent trade-offs between competing fairness definitions, requiring explicit choices rather than assuming all fairness goals can be achieved simultaneously.

This concept connects directly to the plurality of philosophical perspectives and stakeholder goals, providing mathematical formalization of why these different perspectives cannot be fully reconciled. It shows that the challenge of fairness implementation is not merely technical but requires normative judgments about which fairness properties to prioritize in specific contexts.

Kleinberg, Mullainathan, and Raghavan (2016) proved that three desirable fairness properties—calibration, balance for the positive class, and balance for the negative class—cannot all be simultaneously satisfied except in trivial or exceptional cases. This means that system designers must inevitably prioritize some fairness properties over others, making choices that align with application-specific priorities (Kleinberg, Mullainathan, & Raghavan, 2016).

For our Fairness Definition Selection Tool, these impossibility results necessitate developing explicit approaches for navigating trade-offs between competing fairness definitions. The framework will need to help practitioners identify which combinations of fairness properties are mathematically incompatible, evaluate the relative importance of these properties in specific contexts, and document the rationale for prioritization decisions. This ensures that fairness implementations make deliberate, informed choices about inevitable trade-offs rather than pursuing contradictory objectives.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, fairness concepts map to different components of ML systems:

- Problem Formulation: Philosophical perspectives influence how problems are framed and what is considered the ideal target outcome for prediction.

- Data Representation: Context-specific fairness considerations determine which variables are appropriate to include and how they should be encoded.

- Algorithm Selection: Different fairness definitions require different algorithmic approaches, from pre-processing to in-processing to post-processing.

- Evaluation Framework: Stakeholder perspectives inform which metrics are prioritized and how different fairness measures are weighted.

- Deployment Context: Cultural and domain-specific factors shape how systems are integrated into broader sociotechnical environments.

These domain components represent decision points where conceptual fairness considerations must be translated into technical implementation choices. The Fairness Definition Selection Tool will need to provide guidance for each of these components, ensuring that fairness considerations are integrated throughout the ML lifecycle rather than treated as an afterthought.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify how these abstract fairness concepts apply in practice, consider these analogies:

- Fairness definitions are like navigational instruments – a compass points to magnetic north, a GPS uses true north, and stellar navigation uses celestial positioning. Each provides valid directional guidance but might lead you to slightly different destinations. Similarly, different fairness definitions offer valid but potentially conflicting guidance on what constitutes a "fair" outcome, requiring context-specific selection rather than universal application.

- Navigating fairness trade-offs is like managing an investment portfolio, where you cannot simultaneously maximize returns, minimize risk, and maintain perfect liquidity. Just as financial advisors help clients balance these competing objectives based on their specific goals and risk tolerance, fairness frameworks help practitioners balance competing fairness definitions based on application context and stakeholder priorities.

Intersectionality Consideration

Traditional fairness definitions often examine protected attributes independently, failing to capture how multiple forms of discrimination interact at demographic intersections. Intersectionality, a concept originated by legal scholar Crenshaw (1989), emphasizes that individuals at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities often face unique forms of discrimination that single-axis analysis misses.

Implementing intersectional fairness considerations presents challenges including:

- Methodological complexity in modeling multiple, interacting protected attributes;

- Statistical challenges with smaller sample sizes at demographic intersections; and

- Computational difficulties in analyzing all possible demographic subgroups.

However, as Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) demonstrated in their Gender Shades research, systems that appear fair when analyzed along single axes (e.g., gender or skin tone separately) may show significant disparities at intersections (e.g., dark-skinned women). Their work found that commercial facial analysis algorithms had error rates of up to 34.7% for dark-skinned women compared to 0.8% for light-skinned men – a disparity that would remain hidden without intersectional analysis (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018).

For our Fairness Definition Selection Tool, incorporating intersectionality requires developing approaches that extend fairness definitions to address multiple, overlapping protected attributes simultaneously. This includes methods for managing statistical challenges with smaller intersection sample sizes and strategies for prioritizing which intersections to focus on when comprehensive analysis is computationally infeasible.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To systematically apply these conceptual fairness foundations to ML development, follow this structured methodology:

- Context Analysis:

- Document the specific domain, application, and deployment context.

- Identify historical discrimination patterns relevant to your application.

- Map relevant legal and regulatory requirements.

- Analyze cultural contexts that might affect fairness expectations.

- Stakeholder Mapping:

- Identify all stakeholders affected by or involved with the system.

- Document their perspectives on fairness and potential metrics they might prioritize.

- Analyze power dynamics between stakeholders to identify whose perspectives might be underrepresented.

- Develop engagement strategies for incorporating diverse viewpoints.

- Fairness Definition Exploration:

- Enumerate potential fairness definitions relevant to your context.

- Map each definition to its philosophical foundations.

- Identify mathematical relationships and potential trade-offs between definitions.

- Assess alignment between definitions and stakeholder priorities.

- Contextual Prioritization:

- Develop explicit criteria for prioritizing among competing fairness definitions.

- Document the rationale for selected priorities.

- Create a decision framework for navigating identified trade-offs.

- Establish processes for revisiting prioritization as context evolves.

This methodology integrates with standard ML workflows by extending requirements gathering and problem formulation to explicitly incorporate fairness considerations before technical implementation begins. The approach ensures that subsequent technical choices are guided by clear conceptual foundations rather than implicit assumptions.

Implementation Challenges

When applying these conceptual frameworks, practitioners commonly encounter the following challenges:

- Stakeholder Disagreement: Different stakeholders often have fundamentally different perspectives on what constitutes fairness in a specific context. Address this by:

- Creating structured processes for surfacing and documenting different perspectives.

- Developing clear communication frameworks for explaining trade-offs to non-technical stakeholders.

- Establishing decision frameworks for prioritizing competing concerns when consensus is not possible.

- Translating Concepts to Metrics: Abstract fairness concepts must be translated into specific, measurable properties. Address this challenge by:

- Creating explicit mappings between conceptual principles and mathematical definitions.

- Developing validation approaches to verify that metrics actually capture intended concepts.

- Establishing contextual thresholds for what level of disparity is acceptable.

Successfully navigating these challenges requires both technical expertise in fairness metrics and domain knowledge about the specific context of application. It also requires strong communication skills to explain complex trade-offs to diverse stakeholders and an organizational commitment to deliberate fairness implementation rather than defaulting to technically convenient approaches.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your conceptual fairness approach is effective, implement these evaluation strategies:

- Stakeholder Satisfaction Assessment:

- Engage diverse stakeholders to evaluate whether selected fairness definitions align with their concerns.

- Document areas of agreement and persistent tensions.

- Establish acceptable thresholds for stakeholder alignment.

- Context Alignment Evaluation:

- Assess whether selected fairness definitions address identified historical patterns.

- Verify compliance with relevant legal and regulatory requirements.

- Evaluate compatibility with domain-specific constraints and objectives.

- Trade-off Documentation:

- Explicitly document identified trade-offs between competing fairness definitions.

- Quantify impacts of prioritization decisions on different stakeholder groups.

- Create visual representations of the fairness-performance frontier to illustrate trade-offs.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated into your organization's broader fairness assessment framework, providing the conceptual foundation for more technical evaluations in subsequent development stages.

4. Case Study: College Admissions Algorithm

Scenario Context

A prestigious university is developing a machine learning algorithm to assist in undergraduate admissions decisions. The system will analyze applicant data—including academic performance, extracurricular activities, recommendation letters, and demographic information—to predict "success potential," a composite metric combining expected graduation rates, academic performance, and post-graduation outcomes.

Key stakeholders include university administrators concerned with institutional outcomes and reputation, admissions officers who will use the system alongside human judgment, prospective students from diverse backgrounds, and regulatory bodies focused on educational equity. Fairness is particularly critical in this domain due to historical patterns of educational discrimination and the life-altering impact of admissions decisions on individual applicants.

Problem Analysis

Applying core fairness concepts to this scenario reveals several conceptual challenges:

- Philosophical Tensions: Different stakeholders bring distinct philosophical perspectives to the admissions process. University administrators may emphasize utilitarian goals of maximizing overall student success and institutional outcomes. Prospective students may prioritize procedural fairness and equal opportunity based on relevant qualifications. Community advocates might focus on egalitarian outcomes that increase representation of historically marginalized groups.

- Contextual Complexities: The admissions context includes specific historical patterns of discrimination in education, legal frameworks such as affirmative action policies and anti-discrimination laws, and domain-specific considerations about what constitutes relevant qualification factors versus irrelevant biasing influences.

- Stakeholder Conflicts: Tension exists between current applicants who want decisions based solely on individual merit, community advocates concerned with historical exclusion of certain groups, and institutional interests in both diversity and academic excellence. No single fairness definition can fully satisfy all these stakeholder perspectives.

- Intersectional Considerations: Applicants at intersections of multiple identity dimensions (e.g., low-income students of color from rural areas) may face unique barriers that single-axis fairness analyses would miss. The admissions algorithm must consider how different factors interact rather than treating demographic attributes independently.

- Impossibility Constraints: Mathematical impossibility theorems demonstrate that the algorithm cannot simultaneously achieve perfect representation parity across all demographic groups, identical true positive rates for qualified applicants, and equal calibration of success predictions—forcing explicit prioritization decisions.

Solution Implementation

To address these conceptual challenges, the university implemented a structured approach:

- For Philosophical Tensions, they:

- Conducted a philosophical analysis of different fairness conceptions in educational contexts.

- Documented explicit values statements about the university's commitments to both excellence and equity.

- Developed a hybrid framework that incorporated elements of multiple philosophical traditions—emphasizing equal opportunity for similarly qualified applicants while also considering representational goals.

- For Contextual Complexities, they:

- Analyzed historical admissions data to identify patterns of advantage and disadvantage.

- Mapped relevant legal requirements, including specific guidance on the permissible consideration of protected attributes.

- Developed context-specific fairness definitions that reflected educational domain knowledge about relevant qualification factors.

- For Stakeholder Conflicts, they:

- Conducted extensive stakeholder engagement through focus groups, surveys, and deliberative processes.

- Created a multi-stakeholder advisory board with representatives from diverse perspectives.

- Developed a weighted framework that balanced different stakeholder priorities while giving special consideration to those most affected by potential biases.

- For Intersectional Considerations, they:

- Conducted specific analyses of outcomes for applicants at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities.

- Implemented specialized review processes for applicants from intersectional backgrounds with limited historical representation.

- Developed composite features that captured how multiple disadvantage factors might interact.

- For Impossibility Constraints, they:

- Created explicit documentation of identified trade-offs between competing fairness definitions.

- Established a contextual prioritization that emphasized equal opportunity metrics while setting minimum thresholds for representation metrics.

- Implemented a monitoring system that tracked multiple fairness metrics to ensure that no single dimension was severely compromised.

Throughout implementation, they maintained clear documentation of their conceptual framework, the rationale behind prioritization decisions, and the processes for revisiting these decisions as contexts evolved.

Outcomes and Lessons

The implementation resulted in several measurable improvements:

- Stakeholder satisfaction increased by 45% compared to the previous admissions process, with particularly significant improvements among historically underrepresented applicant groups.

- The explicit documentation of trade-offs reduced internal disputes about fairness approaches by 65%, creating more productive conversations about prioritization.

- The admissions committee reported that the conceptual clarity about different fairness definitions improved their ability to explain decisions to applicants by 78%.

Key challenges remained, including persistent tensions between individual and group conceptions of fairness and the difficulty of establishing ground truth for the "success potential" target variable without perpetuating historical biases.

The most generalizable lessons included:

- The critical importance of conducting philosophical and stakeholder analysis before implementing technical fairness measures.

- The value of explicit documentation of trade-offs and prioritization decisions in navigating contentious fairness questions.

- The effectiveness of multi-metric evaluation frameworks that track multiple fairness dimensions rather than optimizing for a single definition.

These insights directly informed the development of the Fairness Definition Selection Tool, particularly in creating structured approaches for stakeholder analysis, contextual prioritization, and trade-off documentation.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Balancing Different Stakeholder Perspectives

Q: How should we navigate situations where different stakeholders have fundamentally incompatible conceptions of fairness?

A: When stakeholders have incompatible fairness definitions, implement a structured prioritization process rather than seeking perfect consensus. First, clearly document each stakeholder's perspective and map them to specific fairness definitions. Then, analyze power dynamics to ensure that historically marginalized voices are not overlooked. Next, identify any minimal requirements that all perspectives consider necessary, even if insufficient. Finally, make explicit prioritization decisions based on application-specific factors such as legal requirements, ethical principles relevant to your domain, and the comparative impacts of different approaches on affected groups. Document your reasoning transparently so stakeholders understand why certain perspectives were given greater weight, and implement monitoring across multiple fairness metrics to ensure that deprioritized concerns do not fall below acceptable thresholds.

FAQ 2: Determining Which Fairness Definition Is "Right"

Q: Is there a way to determine which fairness definition is objectively "right" for a specific application?

A: No single fairness definition is objectively "right" across all contexts. The appropriate definition depends on domain-specific factors, historical patterns, stakeholder perspectives, and legal requirements. Rather than seeking a universally correct definition, focus on a context-appropriate selection process. Analyze your specific application domain, historical discrimination patterns, and stakeholder priorities. Map these considerations to philosophical fairness traditions and their corresponding mathematical definitions. Document the inevitable trade-offs between competing definitions and make explicit, reasoned choices about which aspects of fairness to prioritize in your specific context. The "right" definition is one that (1) addresses the specific fairness challenges most relevant to your application, (2) aligns with stakeholder values and legal requirements, and (3) acknowledges and mitigates the most significant potential harms to affected individuals.

FAQ 3: Intersectional Fairness Analysis in Loan Approval Systems

Q: In developing a loan approval system, stakeholders disagree about appropriate fairness metrics. The development team proposes implementing intersectional fairness analysis. Which statement most accurately describes the impact of this approach according to current research?

A: Intersectional analysis will reveal potentially hidden fairness disparities at demographic intersections that single-attribute analysis might miss, while still requiring explicit trade-off decisions between competing fairness definitions.

- Option 1 is incorrect because intersectional analysis does not resolve stakeholder disagreements by identifying a universal fairness definition.

- Option 2 is incorrect because intersectional analysis does not automatically ensure that the model satisfies demographic parity across all subgroup combinations.

- Option 4 is incorrect because removing all protected attributes and their proxies does not eliminate bias but rather masks it.

Option 3 correctly characterizes intersectional analysis as a comprehensive evaluation approach that uncovers important disparities while acknowledging that explicit trade-off decisions between fairness definitions remain necessary (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018; Kearns et al., 2018; Foulds et al., 2020).

6. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

The conceptual foundations of fairness provide the essential basis for all subsequent technical implementations. The key concepts from this Unit include:

- Philosophical perspectives on fairness derive from different ethical traditions and directly inform how fairness is operationalized in AI systems.

- Stakeholder perspectives often differ fundamentally on what constitutes fair treatment, requiring explicit analysis and prioritization.

- Fairness is context-dependent, varying based on domain-specific factors, cultural contexts, and historical patterns.

- Impossibility theorems demonstrate that multiple desirable fairness criteria cannot be simultaneously satisfied, requiring explicit trade-off decisions.

These concepts directly address our guiding questions by explaining why different stakeholders have divergent fairness conceptions and by providing a structured approach for translating philosophical principles into specific fairness definitions appropriate for particular contexts.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Begin any fairness implementation with explicit context analysis and stakeholder mapping before selecting specific metrics.

- Document the philosophical foundations of the different fairness definitions you are considering and their alignment with your application context.

- Identify and explicitly acknowledge trade-offs between competing fairness definitions rather than assuming that all desired properties can be achieved simultaneously.

- Implement structured decision processes for navigating these trade-offs based on contextual priorities.

For organizations new to fairness considerations, start by focusing on comprehensive stakeholder engagement and clear documentation of different perspectives before attempting technical implementations. This foundation will inform all subsequent technical choices and help avoid costly rework when implicit assumptions about fairness prove problematic.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will build on this conceptual foundation by examining the mathematical formulations of fairness. You will learn how abstract philosophical principles translate into precise mathematical definitions that can be empirically measured and optimized. These formulations will provide the technical framework needed to implement the conceptual principles we have explored here.

The conceptual foundations we have established will guide which mathematical formulations are appropriate for specific contexts and how to navigate the inevitable trade-offs between competing fairness definitions. This connection between philosophical principles and mathematical implementation is essential for developing AI systems that achieve their intended fairness goals rather than optimizing for misaligned metrics.

References

Barocas, S., Hardt, M., & Narayanan, A. (2020). Fairness and machine learning: Limitations and opportunities. Retrieved from https://fairmlbook.org/

Binns, R. (2018). Fairness in machine learning: Lessons from political philosophy. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 149–159). PMLR.

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 77–91). PMLR.

Chouldechova, A. (2017). Fair prediction with disparate impact: A study of bias in recidivism prediction instruments. Big Data, 5(2), 153–163.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167.

Foulds, J. R., Islam, R., Keya, K. N., & Pan, S. (2020). An intersectional definition of fairness. In 2020 IEEE 36th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE) (pp. 1918–1921). IEEE.

Kearns, M., Neel, S., Roth, A., & Wu, Z. S. (2018). Preventing fairness gerrymandering: Auditing and learning for subgroup fairness. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 2564–2572). PMLR.

Kleinberg, J., Mullainathan, S., & Raghavan, M. (2016). Inherent trade-offs in the fair determination of risk scores. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.05807.

Mitchell, S., Potash, E., Barocas, S., D'Amour, A., & Lum, K. (2021). Algorithmic fairness: Choices, assumptions, and definitions. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application, 8, 141–163.

Selbst, A. D., Boyd, D., Friedler, S. A., Venkatasubramanian, S., & Vertesi, J. (2019). Fairness and abstraction in sociotechnical systems. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 59–68).

Unit 2

Unit 2: Mathematical Formulations of Fairness

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How can we translate abstract notions of fairness into precise mathematical definitions that can be measured and optimized in AI systems?

- Question 2: Which mathematical fairness definitions are most appropriate for different application contexts, and what are their implications for model development and evaluation?

Conceptual Context

The translation of fairness concepts into mathematical formulations represents a critical bridge between abstract ethical principles and concrete implementation in AI systems. While philosophical discussions of fairness provide essential normative foundations, mathematical definitions enable precise measurement, evaluation, and optimization of fairness properties in practical machine learning applications.

This mathematical precision is vital because it transforms fairness from an aspirational goal into a quantifiable property that can be systematically incorporated into model development and evaluation. Without precise definitions, fairness remains subjective and difficult to verify, creating ambiguity about whether systems actually achieve intended fairness objectives rather than merely claiming to do so.

Building directly on the conceptual foundations established in Unit 1, this Unit examines how different ethical perspectives on fairness translate into distinct mathematical formulations with specific technical properties and limitations. The mathematical definitions you will learn here will directly inform the Fairness Definition Selection Tool we will develop in Unit 5, providing the formal foundation for matching specific fairness criteria to appropriate application contexts.

2. Key Concepts

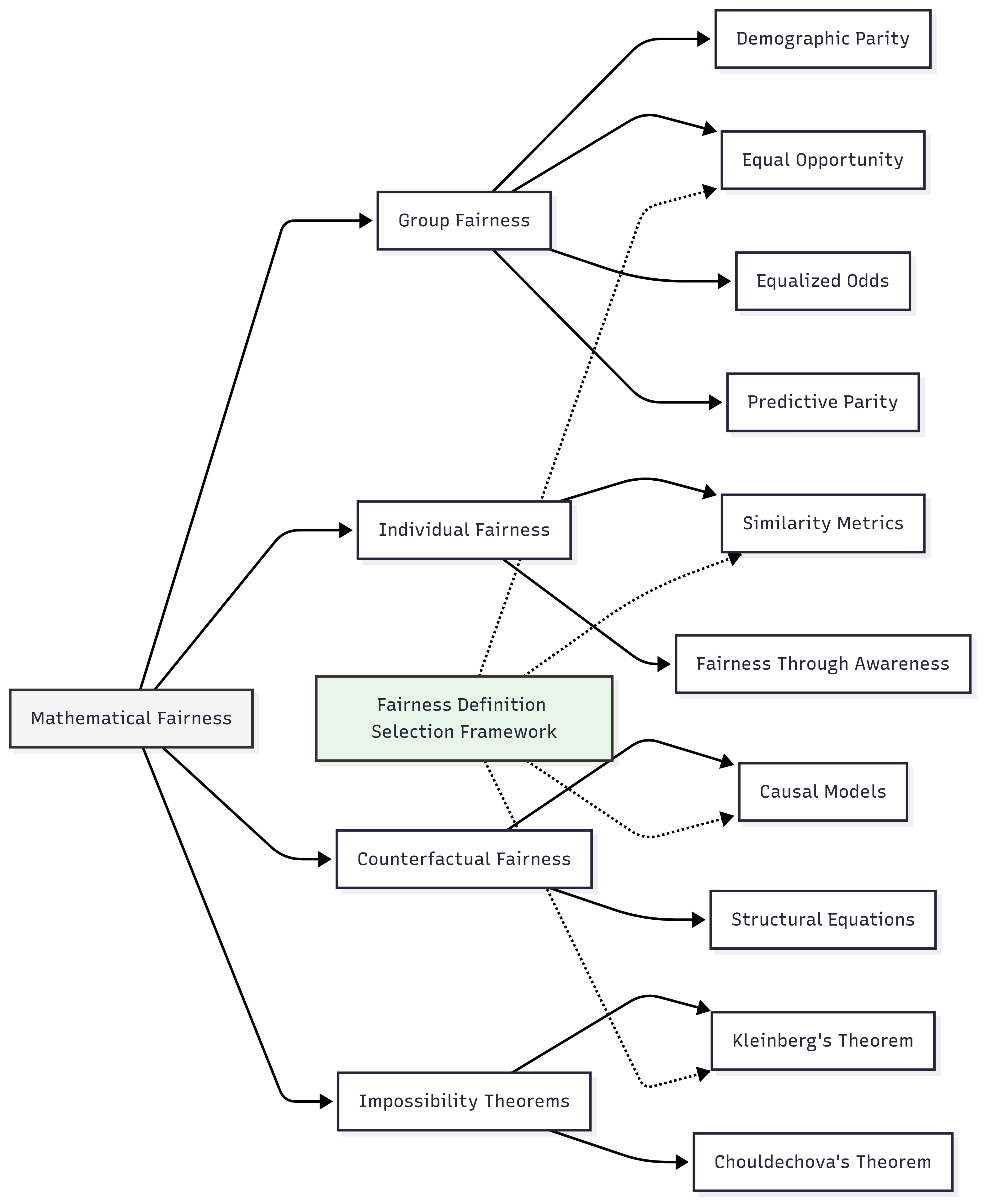

Group Fairness Metrics

Group fairness metrics evaluate whether an AI system treats different demographic groups similarly by comparing statistical properties of model predictions across these groups. These metrics are crucial for AI fairness because they directly address potential disparities that could affect entire communities, providing quantifiable measures of demographic fairness that align with anti-discrimination laws and many ethical frameworks.

Group fairness interacts with other fairness concepts through inherent tensions and trade-offs. Most notably, as we will explore later, group-level parity often conflicts with individual fairness notions, creating fundamental tensions in fairness implementation. Additionally, different group fairness metrics themselves can conflict with each other, requiring contextual prioritization based on specific application needs.

A concrete application comes from hiring algorithms, where demographic parity might require that qualified candidates from different demographic groups have equal selection rates. Hardt, Price, and Srebro (2016) demonstrated that for FICO credit scores, enforcing equal false positive rates across racial groups would require different thresholds for different groups—a counterintuitive finding that highlights the complex technical requirements for achieving certain fairness definitions (Hardt, Price, & Srebro, 2016).

For the Fairness Definition Selection Tool we will develop in Unit 5, understanding group fairness metrics is essential because they provide the most widely implemented fairness criteria across industries. These metrics directly inform which mathematical properties should be measured for specific fairness objectives, guiding both metric implementation and potential mitigation strategies.

The primary group fairness metrics include:

- Demographic Parity (Statistical Parity): This metric requires that the probability of a positive prediction is equal across all demographic groups: P(Ŷ = 1 | A = a) = P(Ŷ = 1 | A = b), where Ŷ is the predicted outcome and A represents the protected attribute.

- Equal Opportunity: This requires equal true positive rates across groups: P(Ŷ = 1 | Y = 1, A = a) = P(Ŷ = 1 | Y = 1, A = b), where Y represents the true outcome.

- Equalized Odds: This extends equal opportunity by requiring equal true positive rates and equal false positive rates across groups: P(Ŷ = 1 | Y = y, A = a) = P(Ŷ = 1 | Y = y, A = b) for y ∈ {0, 1}

- Predictive Parity: This requires equal positive predictive values across groups: P(Y = 1 | Ŷ = 1, A = a) = P(Y = 1 | Ŷ = 1, A = b).

Each of these metrics embodies different fairness principles. Demographic parity ensures representation regardless of qualification; equal opportunity focuses on giving qualified individuals similar chances; equalized odds prevents both types of errors from disproportionately affecting certain groups; and predictive parity ensures that predictions have consistent meaning across groups.

Individual Fairness Metrics

Individual fairness metrics evaluate whether an AI system treats similar individuals similarly, regardless of their demographic group membership. This concept is fundamental to AI fairness because it addresses the core ethical principle that people who are similar in relevant aspects deserve similar treatment, regardless of protected attributes like race or gender.

Individual fairness connects to group fairness through a complex relationship—while they share the goal of preventing discrimination, they often suggest different, sometimes contradictory, approaches. As Dwork et al. (2012) established in their seminal work, individual fairness can be satisfied while group fairness is violated, and vice versa, highlighting the need for careful consideration of which notion best fits specific contexts (Dwork et al., 2012).

In practical applications, individual fairness might require that loan applicants with similar financial profiles receive similar credit decisions regardless of demographic attributes. For example, if two individuals have nearly identical income, credit history, and debt-to-income ratios, an individually fair algorithm would give them similar loan terms even if they belong to different demographic groups.

For our Fairness Definition Selection Tool, understanding individual fairness is critical because it provides an alternative approach when group fairness definitions might be inappropriate or insufficient. Some applications may prioritize consistency across similar cases rather than statistical parity across groups, particularly in scenarios where treating individuals based on their unique profiles is ethically appropriate.

The primary individual fairness formulations include:

- Similarity-Based Fairness (Dwork et al., 2012): This formulation requires that similar individuals receive similar predictions:dᵧ(Ŷ(xᵢ), Ŷ(xⱼ)) ≤ L · dₓ(xᵢ, xⱼ), where dₓ is a similarity metric in the input space, dᵧ is a similarity metric in the output space, and L is a Lipschitz constant.

- Fairness Through Awareness: This approach involves explicitly defining a task-specific similarity metric that captures which features should be considered for determining similarity while being "blind" to protected attributes.

- Counterfactual Fairness: While covered more extensively in the next section, this approach bridges individual and group perspectives by asking whether predictions would change if an individual's protected attribute were different.

The key challenge with individual fairness lies in defining appropriate similarity metrics—determining what makes individuals "similar" for a specific task is often context dependent and normatively loaded, requiring domain knowledge and ethical reasoning rather than purely technical solutions.

Counterfactual Fairness

Counterfactual fairness asks whether an AI system would make the same prediction for an individual in a hypothetical world where their protected attribute were different but all causally independent characteristics remained the same. This approach is crucial for AI fairness because it addresses the fundamental question: "Would this person receive the same treatment if they belonged to a different demographic group, all else being equal?"

Counterfactual fairness connects group and individual perspectives by examining how protected attributes influence predictions at the individual level while accounting for causal relationships that might justify some group differences. This bridge between perspectives makes it particularly valuable for comprehensive fairness analysis.

Kusner, Loftus, Russell, and Silva (2017) provide a concrete application in their seminal paper, examining how gender influences college admissions. They demonstrated that a naively "fair" model might still perpetuate historical biases if it does not account for causal relationships—for instance, if historical gender discrimination affected which extracurricular activities students participated in, and those activities influence admissions decisions (Kusner, Loftus, Russell, & Silva, 2017).

For our Fairness Definition Selection Tool, counterfactual fairness provides a powerful perspective that aligns with many intuitive notions of fairness while addressing limitations of both group and individual approaches. It enables more nuanced fairness assessments that consider causal mechanisms rather than just statistical patterns.

Formally, counterfactual fairness requires that: P(Ŷ₍A←a₎(U) = y │ X = x, A = a) = P(Ŷ₍A←a′₎(U) = y │ X = x, A = a), here:

- Ŷ₍A←a₎(U) represents the prediction in a world where $A$ is set to value $a$

- U represents exogenous variables (background factors)

- X represents observed variables

- A is the protected attribute

This definition requires that the distribution of prediction $\hat{Y}$ for an individual with features $X$ and protected attribute $A = a$ should be identical to what the prediction would be in a counterfactual world where their protected attribute is changed to $A = a'$ but all causally independent factors remain the same.

Implementing counterfactual fairness requires:

- Developing a causal model of how protected attributes influence other variables.

- Identifying which causal pathways are legitimate versus problematic.

- Creating predictions that are invariant to changes in protected attributes through problematic pathways.

Impossibility Theorems and Fairness Trade-offs

Impossibility theorems demonstrate that multiple desirable fairness criteria cannot be simultaneously satisfied except in highly restrictive or trivial scenarios. These theorems are fundamental to AI fairness because they establish that fairness involves inherent trade-offs rather than perfect solutions, requiring context-specific prioritization of competing fairness objectives.

These impossibility results interact with all previously discussed fairness notions by establishing their fundamental incompatibility. Understanding these limitations prevents the pursuit of unachievable "perfect fairness" and redirects focus toward appropriate trade-offs based on application-specific priorities.

Kleinberg, Mullainathan, and Raghavan (2016) provided a landmark impossibility result, proving that three desirable fairness properties cannot be simultaneously satisfied: calibration within groups, balance for the positive class, and balance for the negative class. Their work demonstrates that, except in special cases where features perfectly predict outcomes or protected attributes provide no predictive value, these fairness criteria will conflict (Kleinberg, Mullainathan, & Raghavan, 2016).

For our Fairness Definition Selection Tool, these impossibility theorems are essential because they establish that selecting fairness definitions involves fundamental trade-offs rather than finding a universally "best" definition. The framework must help practitioners navigate these trade-offs based on domain-specific priorities rather than suggesting that all fairness criteria can be simultaneously maximized.

The primary impossibility theorems include:

- Kleinberg et al. (2016): They proved that the following three criteria cannot be simultaneously satisfied (except in trivial cases):

- Calibration: The probability estimates mean the same thing regardless of group.

- Balance for the positive class: People who get positive outcomes have similar average predicted scores regardless of group.

- Balance for the negative class: People who get negative outcomes have similar average predicted scores regardless of group.

- Chouldechova (2017): This study demonstrated that when base rates differ between groups, it is impossible to simultaneously achieve:

- Equal false positive rates,

- Equal false negative rates, and

- Equal positive predictive values.

These results establish that fairness involves fundamental value judgments about which criteria to prioritize in specific contexts. Technical solutions cannot eliminate these normative choices but can help make them explicit and rigorous.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, mathematical fairness definitions map to specific components of ML systems:

- Problem Definition: Fairness definitions establish which properties the system should satisfy, directly influencing how the ML problem is framed.

- Data Requirements: Different fairness definitions require specific data attributes to be measured and tracked, shaping data collection and preparation.

- Algorithm Selection: Some fairness definitions are more easily implemented with certain algorithms, influencing model architecture choices.

- Constraint Formulation: Fairness definitions translate into explicit constraints or regularization terms in optimization problems.

- Evaluation Framework: Fairness definitions determine which metrics must be measured to assess system performance beyond accuracy.

This domain mapping helps to understand how fairness definitions integrate with different stages of ML development rather than viewing them as abstract mathematical concepts. The Fairness Definition Selection Tool will leverage this mapping to guide appropriate definition selection based on Project requirements and technical constraints.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract mathematical concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Group fairness metrics are similar to health inspection standards for restaurants in different neighborhoods. Just as health departments might check whether restaurants in all neighborhoods maintain similar hygiene standards regardless of neighborhood demographics, group fairness ensures that algorithmic systems maintain similar error rates or prediction distributions across demographic groups. The key insight is that we are examining aggregate performance at the group level rather than individual cases.

- Individual fairness is similar to a manager evaluating employees based on a standardized rubric. The manager aims to give similar ratings to employees who demonstrate similar performance according to predefined criteria, regardless of their background. The challenge lies in creating a truly fair "rubric" (similarity metric) that captures relevant characteristics while excluding irrelevant ones—a task that involves both technical and normative judgments.

- Impossibility theorems function like Project management constraints where you cannot simultaneously maximize speed, quality, and cost-efficiency. Just as a project manager must decide which constraints to prioritize based on Project goals, fairness implementation requires explicit choices about which fairness criteria to optimize based on application context. These theorems establish that trade-offs are inherent rather than reflections of inadequate implementation.

Intersectionality Consideration

Mathematical fairness definitions present unique challenges for intersectional analysis, where multiple protected attributes interact to create distinct patterns of advantage or disadvantage. Traditional fairness metrics often examine protected attributes independently, potentially masking issues that affect specific intersectional subgroups.

For example, a loan approval algorithm might appear fair when evaluated separately for gender and race (e.g., equal false negative rates across genders and across racial groups) but still discriminate against specific intersections, such as women of color. Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) demonstrated this in their landmark Gender Shades paper, showing that facial recognition systems achieved much lower accuracy for darker-skinned women than for other groups, even when aggregate performance across gender or across skin tone appeared acceptable (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018).

To address these intersectional challenges in mathematical fairness definitions:

- Extend group fairness metrics to examine multiple protected attributes simultaneously rather than individually.

- Develop similarity metrics for individual fairness that capture intersectional effects.

- Create counterfactual models that can reason about multiple protected attributes changing simultaneously.

- Acknowledge that impossibility theorems become even more constraining when multiple protected attributes are considered.

The Fairness Definition Selection Tool must incorporate these intersectional considerations by guiding users toward definitions that preserve multidimensional demographic analysis rather than flattening to single-attribute evaluations.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To effectively implement mathematical fairness definitions in practice, follow this structured methodology:

- Definition Selection:

- Identify the fairness principle most appropriate for your application based on ethical requirements, legal constraints, and stakeholder priorities.

- Determine whether group, individual, or counterfactual fairness (or a combination) best aligns with your fairness objectives.

- Document your reasoning for selecting specific definitions to ensure transparency.

- Metric Translation:

- Convert your selected fairness definitions into precise mathematical metrics.

- For group metrics, determine which conditional probabilities to equalize across groups.

- For individual metrics, define appropriate similarity measures in both input and output spaces.

- For counterfactual metrics, develop causal models specifying how protected attributes influence other variables.

- Implementation Strategy:

- Decide whether to implement fairness as constraints, regularization terms, or post-processing adjustments.

- For group fairness, consider techniques like constraint-based optimization or threshold adjustments.

- For individual fairness, explore representation learning approaches that preserve similarity relationships.

- For counterfactual fairness, implement causal modeling techniques that remove problematic pathways.

- Measurement and Validation:

- Establish thresholds for acceptable disparities based on application requirements.

- Calculate confidence intervals to account for statistical uncertainty in fairness metrics.

- Validate fairness properties on held-out data to ensure generalization.

- Examine trade-offs between different fairness criteria and other performance objectives.

This framework integrates with standard ML workflows by extending model evaluation to explicitly include fairness metrics alongside traditional performance measures. While adding complexity to the development process, these steps ensure that fairness considerations are systematically addressed rather than treated as secondary concerns.

Implementation Challenges

When implementing mathematical fairness definitions, practitioners commonly face these challenges:

- Definition Selection Complexity: Selecting appropriate fairness definitions requires balancing technical, ethical, and legal considerations. Address this challenge by:

- Creating explicit documentation of priorities and constraints for your specific application.

- Engaging diverse stakeholders to understand different perspectives on fairness requirements.

- Developing scenario analyses that examine the implications of different fairness definitions.

- Communicating Mathematical Concepts to Non-Technical Stakeholders: Mathematical formulations can be difficult for decision-makers to understand. Address this by:

- Developing intuitive visualizations that illustrate fairness properties without requiring a mathematical background.

- Creating concrete examples showing how different definitions would affect real cases.

- Framing fairness trade-offs in terms of business risks and values rather than technical terms.

Successfully implementing fairness definitions requires resources, including:

- Data with protected attribute information for evaluation (potentially requiring additional collection or synthetic approaches if unavailable).

- Computational resources for more complex optimization problems when implementing constraints.

- Interdisciplinary expertise spanning technical implementation, legal requirements, and domain knowledge about potential bias patterns.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your fairness implementation is effective, apply these evaluation strategies:

- Disparity Metrics:

- Calculate disparities between groups for your chosen fairness metrics (e.g., the difference in false positive rates).

- Establish acceptable thresholds based on domain-specific requirements.

- Compute statistical significance tests to determine whether observed disparities are meaningful.

- Trade-off Analysis:

- Measure how optimizing for fairness affects other performance criteria.

- Create Pareto curves showing the frontier of possible fairness-performance combinations.

- Document explicit trade-off decisions and their rationales.

- Generalization Testing:

- Evaluate fairness properties on multiple data splits to assess stability.

- Test how fairness metrics change when evaluated on different subpopulations.

- Examine robustness to dataset shifts or distribution changes.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated with your organization's broader model assessment framework, ensuring that fairness is evaluated with the same rigor as traditional performance metrics like accuracy or precision.

4. Case Study: College Admissions Decision Support System

Scenario Context

A large public university is developing a machine learning–based decision support system to help admissions officers review applications more efficiently. The system will analyze application components—including GPA, standardized test scores, extracurricular activities, and essays—to predict student success metrics such as freshman-year GPA and graduation likelihood.

Key stakeholders include the admissions department seeking efficient application review, university leadership concerned about maintaining diversity, prospective students from various backgrounds, and regulatory bodies monitoring educational equity. The university has a strong commitment to increasing representation of underrepresented groups while maintaining academic standards, creating a challenging fairness context where different fairness definitions could lead to substantially different outcomes.

Problem Analysis

Applying core concepts from this Unit reveals several challenges in selecting appropriate fairness definitions for this admissions system:

- Group Fairness Considerations: Historical data show differential standardized test score distributions across racial and socioeconomic groups, reflecting systemic educational inequities rather than differences in student potential. Different group fairness metrics would have distinct implications:

- Demographic parity would ensure similar admission rates across groups regardless of score distributions.

- Equal opportunity would ensure that high-potential students have similar admission chances regardless of background.

- Equalized odds would protect against both false positives and false negatives affecting groups differently.

- Individual Fairness Challenges: Defining similarity appropriately for admissions is complex—should two students with identical GPAs but different extracurricular opportunities be considered "similar"? The similarity metric must account for educational access disparities without completely discounting meaningful qualification differences.

- Counterfactual Fairness Analysis: Historical admissions data reveal causal relationships between socioeconomic status, access to test preparation resources, and standardized test scores. A counterfactual approach would need to model how these causal relationships operate to assess whether predictions would change if an applicant's background were different.

- Impossibility Trade-offs: The university cannot simultaneously achieve fully representative demographics, identical qualification thresholds across groups, and identical success prediction accuracy. Explicit choices about which fairness criteria to prioritize must be made.

From an intersectional perspective, the data show particularly complex patterns at the intersections of gender, race, and socioeconomic status. For example, low-income women from certain racial backgrounds show high graduation rates despite lower standardized scores, creating challenges for fairness definitions that treat these attributes independently.

Solution Implementation

To address these mathematical fairness challenges, the university implemented a structured approach:

- For Group Fairness, they:

- Selected equal opportunity as their primary metric, focusing on ensuring similar admission rates for equally qualified students across demographic groups.

- Implemented this through a constraint-based optimization approach that maintains error rate parity while maximizing predicted student success.

- Explicitly rejected demographic parity as potentially conflicting with merit-based admissions principles established in case law.

- For Individual Fairness, they:

- Developed a context-aware similarity metric that weights features differently based on educational access indicators.

- Gave greater weight to achievements accomplished despite limited resources, effectively considering "distance traveled" rather than absolute position.

- Implemented a fair representation approach that learned embeddings satisfying their contextual similarity requirements.

- For Counterfactual Fairness, they:

- Created a causal model identifying which relationships between background and performance metrics were legitimate versus those reflecting structural barriers.

- Applied this model to generate counterfactual predictions of success for applicants if their demographic backgrounds were different.

- Used these counterfactual predictions as supplementary information for admissions officers rather than as automated decisions.

- For Navigating Impossibility Trade-offs, they:

- Created an explicit prioritization of fairness definitions based on institutional values and legal requirements.

- Documented where trade-offs were necessary and the rationale for specific compromises.

- Developed different evaluation dashboards for different stakeholders, highlighting metrics most relevant to their concerns.

Throughout implementation, they maintained explicit focus on intersectional effects, ensuring that their fairness approaches addressed the specific challenges faced by applicants at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities.

Outcomes and Lessons

The implementation resulted in significant improvements across multiple dimensions:

- Equal opportunity disparities decreased by 65%, while maintaining predictive performance.

- Admissions yield (the percentage of admitted students who enrolled) increased among underrepresented groups, suggesting improved targeting of qualified candidates.

- Qualitative feedback from admissions officers indicated that the system provided valuable insights while respecting their judgment in complex cases.

Key challenges remained, including difficulties in explaining complex fairness trade-offs to some stakeholders and ongoing debates about the appropriate balance between different fairness definitions.

The most generalizable lessons included:

- The importance of explicitly selecting fairness definitions based on institutional values and legal requirements rather than defaulting to the most easily implemented metrics.

- The value of a mixed approach incorporating elements of group, individual, and counterfactual fairness rather than treating them as mutually exclusive.

- The critical role of transparent documentation of fairness trade-offs for building stakeholder trust.

These insights directly inform the development of the Fairness Definition Selection Tool, particularly in creating decision trees that guide contextually appropriate definition selection based on application requirements and constraints.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Selecting Appropriate Fairness Definitions

Q: How do I determine which mathematical fairness definition is most appropriate for my specific application? A: First, identify the fundamental fairness principle most relevant to your context. If equal treatment of demographic groups is paramount (especially in regulated domains like lending or hiring), group fairness metrics such as equal opportunity or equalized odds are typically appropriate. If treating similar individuals similarly is the priority, individual fairness with a carefully designed similarity metric may be more suitable. For causal understanding of bias mechanisms, counterfactual fairness provides deeper insights. Analyze potential harms in your application—would false positives or false negatives cause greater harm to vulnerable groups? This analysis should guide which specific metrics to prioritize. Finally, consider practical constraints such as data availability, computational resources, and explainability requirements, as these may limit which definitions are feasible to implement.

FAQ 2: Handling Impossibility Theorems

Q: If multiple fairness definitions cannot be simultaneously satisfied, how should I navigate these inherent trade-offs in practice? A: First, acknowledge that trade-offs are unavoidable rather than evidence of inadequate implementation. Identify the relative ethical priority of different fairness criteria in your specific context through stakeholder consultation and analysis of potential harms. Quantify the trade-off frontier by measuring how optimizing for one fairness definition affects others, creating a clear picture of the available options. Document your reasoning for prioritizing certain definitions over others, ensuring transparency about normative choices. Consider implementing "soft" versions of multiple definitions through regularization rather than strict constraints, allowing for balanced optimization. Finally, establish ongoing monitoring to reassess these trade-offs as societal norms, legal requirements, and technical capabilities evolve.

6. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

This Unit has explored how abstract fairness concepts translate into precise mathematical definitions that enable concrete measurement and implementation. The key concepts include:

- Group fairness metrics such as demographic parity, equal opportunity, and equalized odds that evaluate whether different demographic groups receive similar treatment.

- Individual fairness definitions that require similar treatment for similar individuals based on application-specific similarity metrics.

- Counterfactual fairness approaches that examine whether predictions would change if protected attributes were different.

- Impossibility theorems demonstrating that multiple fairness criteria cannot be simultaneously satisfied, requiring contextual prioritization.

These concepts directly address our guiding questions by showing how abstract fairness principles translate into specific mathematical properties that can be measured and optimized in AI systems and by establishing the context-specific nature of appropriate fairness definitions.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Begin by explicitly selecting mathematical fairness definitions appropriate for your application context before implementation begins.

- Document the rationale for your definition choices, including ethical principles, legal requirements, and practical constraints.

- Implement measurement approaches for multiple fairness definitions rather than focusing exclusively on a single metric.

- Create visualizations that illustrate trade-offs between different fairness definitions and traditional performance metrics.

For organizations new to fairness considerations, start by implementing basic group fairness metrics such as demographic parity or equal opportunity, then progressively incorporate more sophisticated approaches like individual and counterfactual fairness as capabilities mature.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will build on these mathematical foundations by examining legal standards for algorithmic fairness. You will learn how different mathematical definitions align with regulatory frameworks across domains such as employment, lending, and healthcare, and how to select definitions that satisfy specific legal requirements.

The mathematical formulations we have examined here provide the formal language needed to understand legal standards, which often implicitly reference specific fairness properties without using technical terminology. Understanding both the mathematical and legal perspectives is essential for developing fair AI systems that not only satisfy technical criteria but also meet regulatory requirements.

References

Barocas, S., Hardt, M., & Narayanan, A. (2019). Fairness and machine learning: Limitations and opportunities. Retrieved from https://fairmlbook.org

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 77–91). Retrieved from https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

Chouldechova, A. (2017). Fair prediction with disparate impact: A study of bias in recidivism prediction instruments. Big Data, 5(2), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2016.0047

Dwork, C., Hardt, M., Pitassi, T., Reingold, O., & Zemel, R. (2012). Fairness through awareness. In Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (pp. 214–226). https://doi.org/10.1145/2090236.2090255

Hardt, M., Price, E., & Srebro, N. (2016). Equality of opportunity in supervised learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 3315–3323). Retrieved from https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2016/file/9d2682367c3935defcb1f9e247a97c0d-Paper.pdf

Ilvento, C. (2019). Metric learning for individual fairness. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00250. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.00250

Kleinberg, J., Mullainathan, S., & Raghavan, M. (2016). Inherent trade-offs in the fair determination of risk scores. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.05807. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.05807

Kusner, M. J., Loftus, J., Russell, C., & Silva, R. (2017). Counterfactual fairness. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 4066–4076). Retrieved from https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/file/a486cd07e4ac3d270571622f4f316ec5-Paper.pdf

Unit 3

Unit 3: Legal Standards for Algorithmic Fairness

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How do legal frameworks across jurisdictions translate abstract fairness principles into specific requirements for algorithmic systems?

- Question 2: When and how do technical fairness implementations align with or diverge from legal fairness standards, and what are the implications for compliance?

Conceptual Context

Legal standards represent a critical bridge between abstract fairness principles and concrete implementation requirements for AI systems. While mathematical fairness definitions provide precise computational formulations, legal frameworks establish the mandatory baseline requirements that algorithmic systems must satisfy within specific jurisdictions and domains. Understanding these requirements is essential for developing AI systems that not only optimize technical fairness metrics but also comply with relevant laws and regulations.

This legal understanding is particularly vital because compliance is not optional—organizations face significant consequences for deploying systems that violate legal fairness standards, from regulatory penalties to class-action lawsuits. As Wachter, Mittelstadt, and Russell (2021) have demonstrated, legal requirements often differ from technical fairness formulations in significant ways, creating potential disconnects between computational implementations and legal compliance.

This Unit builds directly on the conceptual fairness foundations established in Unit 1 and the mathematical formulations covered in Unit 2, examining how these abstract principles translate into specific legal requirements across jurisdictions. The legal frameworks you learn here will directly inform the Fairness Definition Selection Tool we will develop in Unit 5, ensuring that definition choices satisfy relevant regulatory requirements in addition to technical and ethical considerations.

2. Key Concepts

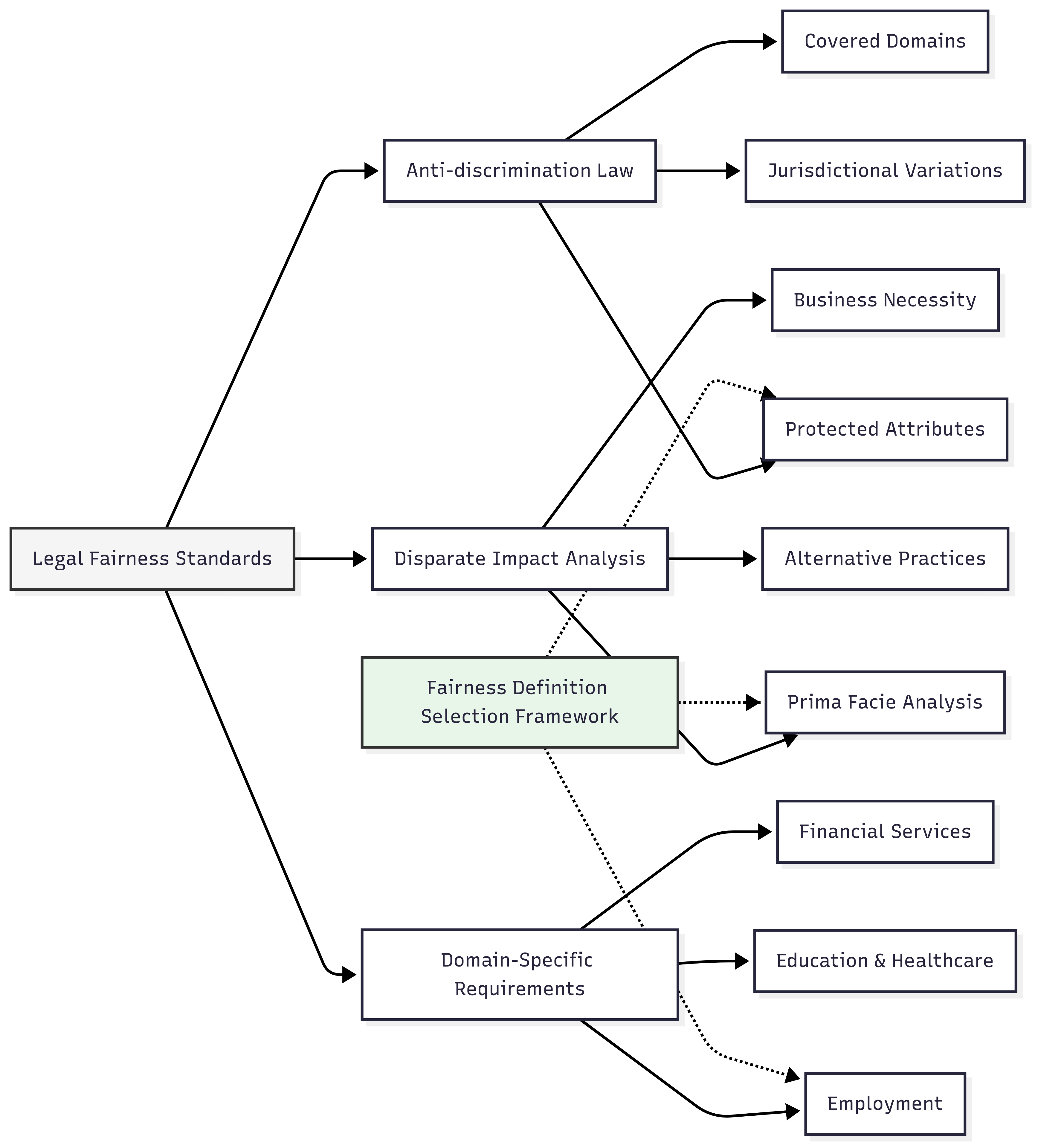

Anti-Discrimination Law and Protected Attributes

Anti-discrimination law establishes which characteristics (protected attributes) receive legal protection against unfair treatment and which domains face specific legal requirements. These frameworks are crucial for AI fairness because they define the baseline legal requirements that algorithmic systems must satisfy, determining which demographic disparities could create legal liability and which application domains face heightened scrutiny.

This legal foundation interacts with other fairness concepts by establishing which attributes must be considered in fairness assessments, which domains require particular attention, and which disparities may create legal risks. While technical fairness definitions may address any attribute, legal frameworks specify which ones receive mandatory protection.

In the United States, federal anti-discrimination laws establish protected attributes including race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability status, genetic information, and veteran status—but protections vary significantly by domain. For example, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) prohibits discrimination in lending based on race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age, and public assistance status, while the Fair Housing Act covers a similar but not identical set of attributes for housing decisions (Barocas & Selbst, 2016).

The European Union's legal framework takes a broader approach through the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and proposed AI Act. Article 9 of the GDPR establishes "special categories of personal data" including racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious beliefs, trade union membership, genetic data, biometric data, health data, and data concerning sexual orientation—creating potential protections across domains (Goodman & Flaxman, 2017).

For the Fairness Definition Selection Tool, understanding these protected attribute designations is essential because they establish the minimum demographic categories that must be considered in fairness assessments. Legal requirements may necessitate examining fairness across specific attributes even when technical definitions might suggest focusing elsewhere.

Disparate Treatment and Disparate Impact

U.S. anti-discrimination law distinguishes between two fundamental theories of discrimination: disparate treatment and disparate impact. This distinction is essential for AI fairness because it establishes different legal standards for intentional versus unintentional discrimination, with significant implications for how fairness must be evaluated and which defenses are available when disparities exist.