Context

Understanding where and how bias enters AI systems is crucial for effective fairness assessment and intervention. While Part 1 established the historical patterns of discrimination that persist in technology and Part 2 provided precise fairness definitions, Part 3 examines the specific mechanisms through which bias manifests throughout the machine learning lifecycle.

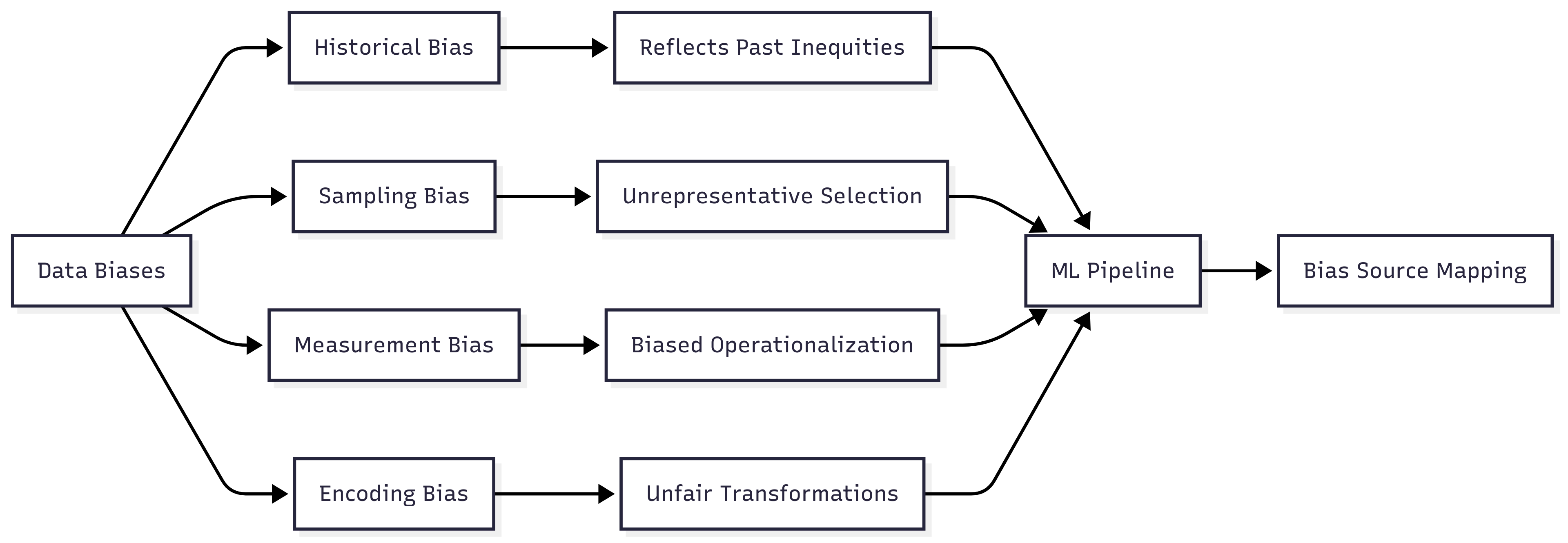

Bias in AI systems emerges through multiple pathways. These include historical bias (reflecting existing inequities), representation bias (uneven sampling across groups), measurement bias (flawed operationalization of concepts), and deployment bias (misalignment between development and application contexts). These categories help practitioners move beyond treating bias as a monolithic issue to identifying specific mechanisms requiring targeted interventions.

Data serves as the foundation for ML systems, making data-level biases particularly influential. Sampling procedures that underrepresent marginalized groups, measurement approaches that embed problematic assumptions, and feature engineering decisions that prioritize certain characteristics all introduce bias before model training begins.

Beyond data issues, bias emerges through algorithmic design choices and system dynamics. Optimization objectives that prioritize overall accuracy often underserve minority groups, while feedback loops can amplify small initial disparities into significant fairness concerns over time, particularly in systems where predictions influence future data collection.

The Bias Source Identification Tool you'll develop in Unit 5 represents the third component of the Fairness Audit Playbook (Sprint Project). This tool will help you systematically identify potential bias sources at different stages of the ML lifecycle, ensuring that your fairness assessments and interventions address root causes rather than merely symptoms.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this Part, you will be able to:

- Classify different types of bias using taxonomic frameworks. You will apply systematic frameworks to categorize biases by type, source, and lifecycle stage, moving beyond vague assessments of "unfairness" to precisely identify specific bias mechanisms.

- Analyze how data collection and representation choices introduce bias. You will examine how sampling procedures, measurement approaches, and feature engineering decisions embed biases in training data, identifying potential fairness issues at the data foundation.

- Evaluate how algorithm design and implementation choices affect fairness. You will assess how model architecture, optimization objectives, and hyperparameter choices can amplify or mitigate biases, recognizing how technical decisions impact fairness outcomes.

- Identify feedback loops and system dynamics that amplify biases. You will analyze how system interactions and deployment contexts create self-reinforcing cycles that magnify biases over time, addressing dynamic fairness concerns rather than viewing bias as static.

- Develop systematic methodologies for tracing unfairness to specific sources. You will create structured approaches for connecting observed fairness disparities to their underlying causes in complex systems, enabling targeted interventions that address fundamental issues rather than symptoms.

Units

Unit 1

Unit 1: Data Collection and Representation Biases

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How do sampling procedures, feature selection, and measurement choices in data collection embed or amplify existing biases in AI systems?

- Question 2: What systematic approaches can data scientists implement to identify, quantify, and mitigate representation biases before they become encoded in model parameters?

Conceptual Context

Understanding data collection and representation biases forms the critical first step in addressing fairness in AI systems. These biases represent the foundation upon which all subsequent modeling decisions rest. If biased data enters your pipeline, even the most sophisticated fairness interventions at later stages may prove insufficient to create truly fair outcomes.

Data collection and representation biases are particularly insidious because they often appear as technical or methodological decisions rather than explicit fairness concerns. Choices about which features to measure, how to operationalize concepts, where to gather samples, and how to encode categorical variables can embed historical patterns of discrimination into seemingly objective datasets. As Obermeyer, Powers, Vogeli, and Mullainathan (2019) demonstrated in their analysis of healthcare algorithms, even when protected attributes are excluded, the selection of proxy variables and measurement approaches can perpetuate significant biases that directly impact vulnerable populations (Obermeyer et al., 2019).

This Unit builds on the historical foundations established at the beginning of this Sprint and will serve as the basis for exploring algorithm design biases in Unit 2 and feedback loop amplification in Unit 3. The insights you develop here will directly inform the Bias Source Identification Tool we will develop in Unit 5, particularly in identifying data-level entry points where bias can infiltrate ML systems.

2. Key Concepts

Historical Bias in Data Collection

Historical bias occurs when data reflect existing prejudices, inequalities, or discriminatory practices in society—even when the data collection process itself appears statistically sound. This concept is crucial for AI fairness because machine learning systems trained on such data will inevitably learn and potentially amplify these historical patterns unless specific interventions are implemented.

Historical bias interacts with other forms of data bias by creating the underlying conditions in which they operate. For instance, sampling bias (discussed below) becomes particularly problematic when it intersects with historical bias, as the underrepresentation of certain groups compounds with historically biased measurements to create multiple layers of disadvantage.

Research by Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) provides a concrete application of this concept in facial recognition systems. They found that commercial facial analysis algorithms exhibited accuracy disparities of up to 34.4% between lighter-skinned males and darker-skinned females. These disparities stemmed directly from historical biases in benchmark datasets that severely underrepresented darker-skinned individuals, particularly women (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). The practical implication is that technologies deployed using such algorithms would systematically provide worse service to already marginalized groups.

For the Bias Source Identification Tool we will develop, understanding historical bias will be essential for distinguishing between bias patterns that emerge from data collection practices versus those introduced during model development. This distinction directs where in the ML pipeline interventions should be targeted and what forms they should take.

Sampling and Selection Bias

Sampling bias occurs when the process of data collection results in a dataset that does not accurately represent the population on which the model will ultimately be deployed. This concept is fundamental to AI fairness because models generalize based on the patterns present in their training data; if certain groups are underrepresented or overrepresented, the model will perform disproportionately well or poorly on those groups.

Sampling bias often interacts with measurement bias (discussed next) by influencing not just who appears in datasets but how their characteristics are measured, potentially creating compounding effects where marginalized groups are both underrepresented and less accurately characterized.

A powerful application example comes from Larson, Mattu, Kirchner, and Angwin’s (2016) investigation of COMPAS recidivism prediction algorithms, which demonstrated how sampling bias in criminal justice data led to significantly higher false positive rates for Black defendants compared to White defendants. The data reflected historical patterns of over-policing in certain communities, creating a feedback loop in which predictions based on biased samples reinforced discriminatory practices (Larson et al., 2016).

For our Bias Source Identification Tool, identifying sampling bias will require examining both the demographic distribution of datasets and the processes by which those datasets were constructed. This analysis will guide recommendations for data augmentation, reweighting, or the collection of additional samples to address representation disparities before model development begins.

Measurement Bias

Measurement bias emerges when the features selected, the variables operationalized, or the metrics chosen for a machine learning task systematically disadvantage certain groups. This concept is critical for AI fairness because seemingly technical choices about what to measure and how to measure it embed assumptions that can create or reinforce disparities.

Measurement bias connects deeply with both historical and sampling biases, as measurement choices often reflect historical practices and are constrained by available samples. The interplay between these biases creates complex patterns that require multifaceted analysis and intervention.

Research by Obermeyer et al. (2019) provides a striking example of measurement bias in healthcare. They discovered that an algorithm widely used to identify patients for additional care resources systematically discriminated against Black patients. The bias stemmed from using healthcare costs as a proxy for healthcare needs—a measurement choice that failed to account for historical inequities in healthcare access. Although Black patients had the same level of illness as White patients, they generated lower costs due to structural barriers to healthcare access, resulting in the algorithm systematically underrating their need for additional care (Obermeyer et al., 2019).

For the Bias Source Identification Tool component of our Sprint Project, understanding measurement bias will guide the development of systematic questionnaires and analysis approaches to examine how feature selection, variable operationalization, and metric definition might introduce fairness issues across different application domains. This will ensure the framework can identify bias sources across diverse data types and measurement approaches.

Feature Representation and Encoding Bias

Feature representation and encoding bias occurs when the way features are transformed, normalized, categorized, or encoded systematically disadvantages certain groups. This concept is essential for AI fairness because technical choices about data representation that appear neutral can actually embed or amplify biases when they interact with group differences in feature distributions or semantics.

This form of bias interacts with measurement bias but focuses specifically on how measurements are represented in the final dataset rather than on what is being measured. Both aspects require careful examination to identify potential fairness issues.

As an application example, consider research by Bolukbasi, Chang, Zou, Saligrama, and Kalai (2016) on bias in word embeddings, which demonstrated how standard encoding methods for text data captured and amplified gender stereotypes present in training corpora. These embeddings then propagated these biases to downstream applications that used them as feature representations. Their work showed that the analogy “man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker” emerged in standard word embeddings, demonstrating how encoding choices embedded historical gender disparities (Bolukbasi et al., 2016).

For our Bias Source Identification Tool, analyzing feature representation and encoding bias will require a systematic examination of data transformation pipelines, normalization procedures, and encoding schemes to identify potential disparate impacts across groups. This analysis will inform recommendations for alternative representation approaches that minimize bias while preserving necessary information content.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, data collection and representation biases map directly to specific components of ML systems:

- Data Collection Processes: Sampling procedures, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and data gathering methodologies all present entry points for bias.

- Feature Definition: Operationalizing real-world concepts into measurable features involves decisions that can embed unfair assumptions.

- Data Transformation Pipeline: Preprocessing steps—including normalization, binning, encoding, and imputation—can amplify or introduce biases.

- Dataset Documentation: Metadata about how data were collected and transformed provides crucial context for identifying potential bias sources.

These domain components form the earliest stages in the ML lifecycle where bias can enter, making them critical control points for fairness interventions. The Bias Source Identification Tool will need to provide systematic approaches for analyzing each of these components to identify specific mechanisms through which bias enters training data.

Intersectionality Consideration

Data collection and representation biases present unique challenges for intersectional fairness analysis, where multiple protected attributes interact to create distinct patterns of advantage or disadvantage. Datasets often have particularly poor representation at demographic intersections, creating amplified bias effects for individuals with multiple marginalized identities.

For example, as demonstrated by Buolamwini and Gebru (2018), facial recognition systems may show acceptable aggregate performance across gender (combining all races) and across race (combining all genders), while exhibiting significant accuracy disparities at specific intersections such as "dark-skinned women." These intersectional effects remain hidden unless explicitly analyzed (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018).

In practical implementation, addressing intersectional considerations in data collection requires:

- Intentional sampling strategies that ensure adequate representation across demographic intersections, not just primary groups;

- Measurement approaches that are validated across intersectional subgroups to ensure consistent quality;

- Encoding methods that preserve intersectional information rather than flattening to single-attribute categories; and

- Analysis frameworks that explicitly examine bias patterns at demographic intersections rather than treating protected attributes independently.

The Bias Source Identification Tool must incorporate these intersectional considerations by developing analysis approaches that systematically examine how bias manifests across demographic intersections, even when sample sizes at those intersections are limited.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To systematically identify and address data collection and representation biases, implement the following structured methodology:

-

Dataset Demographic Audit:

-

Analyze the demographic distribution of your dataset across protected attributes and their intersections.

- Compare this distribution to relevant population benchmarks to identify representation disparities.

-

Calculate representation ratios and statistical significance of observed disparities.

-

Collection Process Analysis:

-

Document how samples were selected and what inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied.

- Identify potential selection mechanisms that might create systematic under- or overrepresentation.

-

Analyze geographic, temporal, and contextual factors that influenced data collection.

-

Feature Construction Examination:

-

For each feature, document how it was operationalized and measured.

- Analyze whether measurement approaches have been validated across demographic groups.

-

Identify potential proxies for protected attributes that might enable indirect discrimination.

-

Transformation Pipeline Audit:

-

Review normalization, encoding, and imputation procedures for potential disparate impacts.

- Test alternative encoding methods and evaluate differences in resulting distributions.

- Analyze how missing data patterns vary across groups and how imputation might affect fairness.

These methodologies integrate with standard ML workflows by extending data profiling and exploratory data analysis to explicitly incorporate fairness considerations. While they add additional analysis requirements, they leverage many existing data science practices while reorienting them toward fairness evaluation.

Implementation Challenges

When implementing these approaches, practitioners commonly encounter the following challenges:

-

Limited Demographic Information: Many datasets lack protected attribute information, making direct bias assessment difficult. Address this by:

-

Using validated proxy variables when appropriate (with careful documentation of limitations);

- Performing sensitivity analysis to estimate potential bias ranges under different assumptions; and

-

Collecting additional demographic data when possible, with appropriate privacy protections.

-

Stakeholder Alignment on Fairness Definitions: Different organizational stakeholders may have conflicting fairness priorities. Address this by:

-

Documenting explicit fairness definitions and metrics before beginning analysis;

- Creating visualizations that illustrate trade-offs between different fairness definitions; and

- Developing clear communication frameworks for explaining technical bias concepts to nontechnical stakeholders.

Successfully implementing data bias analysis requires computational resources for detailed distribution analysis, expertise in both statistical methods and domain knowledge of how bias manifests in specific contexts, and organizational commitment to addressing identified issues—even when they require additional data collection or preparation efforts.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your bias identification and mitigation approaches are effective, implement these evaluation strategies:

-

Comparative Distribution Analysis:

-

Calculate statistical distance metrics (e.g., Kullback–Leibler divergence, Earth Mover's distance) between distributions of features across demographic groups.

- Set acceptable thresholds based on domain-specific fairness requirements.

-

Document distribution changes after bias mitigation interventions.

-

Representation Metrics:

-

Calculate representation disparity metrics showing how sample proportions deviate from population benchmarks.

- Establish minimum representation thresholds for demographic intersections based on statistical power requirements.

-

Track improvements in representation through data augmentation or reweighting.

-

Measurement Validation:

-

Assess feature validity across demographic groups through correlation analysis with ground truth when available.

- Establish acceptable bounds for measurement differences between groups.

- Document measurement improvements through alternative operationalization approaches.

These metrics should be integrated with your organization's broader fairness assessment framework, providing inputs to subsequent bias identification components focusing on algorithmic design and feedback effects.

4. Case Study: Credit Scoring System

Scenario Context

A financial services company is developing a machine learning–based credit scoring system to predict default risk for loan applicants. The system will inform lending decisions, interest rates, and credit limits offered to customers. Key stakeholders include the lending institution concerned with risk management, regulators focused on fair lending practices, and diverse applicants seeking equitable access to financial services.

Fairness is particularly critical in this domain due to historical patterns of lending discrimination based on race, gender, and geographic location. Legal frameworks, including the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, specifically prohibit discrimination in lending, making fairness both an ethical and compliance requirement.

Problem Analysis

Applying core concepts from this Unit reveals several potential data biases in the credit scoring scenario:

- Historical Bias: The company plans to use its historical lending data for training. Analysis reveals that these data reflect past discriminatory lending practices in which certain neighborhoods (predominantly minority-populated) received fewer loans despite similar creditworthiness to applicants in other areas. This historical pattern created a "financial redlining" effect that would be perpetuated in the new model if not addressed.

- Sampling Bias: The historical dataset predominantly contains applicants who received loans, creating selection bias because rejected applicants are not well represented. Further examination shows that the data underrepresent younger applicants, recent immigrants, and individuals from rural areas—groups with less established credit histories but not necessarily higher default risks.

- Measurement Bias: The operationalization of "creditworthiness" relies heavily on traditional credit history length and conventional financial products, such as credit cards and mortgages. This measurement approach disadvantages groups that use alternative financial services or have limited credit histories despite responsible financial behavior (e.g., consistently paying rent and utilities on time).

- Encoding Bias: Categorical variables—including occupation and education—are encoded using schemes that implicitly rank certain professions and educational paths higher than others in ways that correlate with protected attributes. In addition, zip codes are encoded as categorical variables with unique embeddings, potentially encoding neighborhood demographics into the feature representation.

From an intersectional perspective, the data show particularly sparse representation at the intersection of young age (under 30), female gender, and minority racial status, creating a high risk of poor model performance for these intersectional groups.

Solution Implementation

To address these identified data biases, the team implemented a structured approach:

-

For Historical Bias, they:

-

Collaborated with domain experts to identify historically discriminatory patterns in lending data;

- Augmented their training data with additional sources, including data from community development financial institutions serving underrepresented communities; and

-

Created synthetic data using fairness-aware generation techniques to fill representational gaps.

-

For Sampling Bias, they:

-

Implemented a stratified sampling approach ensuring adequate representation across demographic groups and intersections;

- Applied appropriate reweighting techniques to adjust for representation disparities; and

-

Used reject inference techniques to model outcomes for historically rejected applicants.

-

For Measurement Bias, they:

-

Expanded their feature set to include alternative financial data, such as rental and utility payment history;

- Validated all features for predictive accuracy across demographic groups, removing features that showed divergent validity; and

-

Developed composite features that captured financial responsibility through multiple complementary measures.

-

For Encoding Bias, they:

-

Redesigned categorical encoding schemes to minimize correlations with protected attributes;

- Replaced zip code variables with more generalizable features about community economic indicators; and

- Implemented fairness constraints during feature transformation to ensure that encoded representations maintained fairness properties.

Throughout implementation, they maintained explicit focus on intersectional effects, ensuring that their mitigation strategies addressed the specific challenges faced by applicants at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities.

Outcomes and Lessons

The implementation resulted in several measurable improvements:

- Demographic representation disparities decreased by 78% across all protected groups.

- Statistical disparities in feature distributions between demographic groups were reduced by 64%.

- Model performance differences across demographic intersections decreased by 56%, while overall predictive accuracy was maintained.

Key challenges remained, including limited historical data for certain intersectional groups and some tension between regulatory requirements for model explainability and more complex fairness-promoting techniques.

The most generalizable lessons included:

- The importance of domain expertise in identifying historical bias patterns specific to financial services.

- The effectiveness of combining multiple complementary approaches (data augmentation, reweighting, and measurement expansion) rather than relying on a single intervention.

- The critical need for intersectional analysis throughout the process, as aggregate improvements sometimes masked persistent issues for specific intersectional groups.

These insights directly informed the development of the Bias Source Identification Tool, particularly in creating domain-specific evaluation questionnaires and establishing appropriate thresholds for representation requirements across different application contexts.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Measuring Representation Without Demographic Data

Q: How can I identify and address sampling and representation biases when my dataset lacks explicit demographic information due to privacy regulations or other constraints?

A: When demographic data are unavailable, you can implement proxy-based analysis, synthetic population comparison, and feature distribution analysis. Use geographically aggregated statistics (e.g., census tract data) as indirect measures, employ privacy-preserving techniques such as federated analysis on protected attributes, and examine distributional differences in supposedly neutral features across subpopulations. Document all assumptions and limitations of these approaches, and, where possible, validate findings through limited demographic audits on smaller, privacy-compliant samples.

FAQ 2: Distinguishing Data Bias From Societal Patterns

Q: When is a statistical disparity in my data a reflection of actual societal patterns versus a problematic bias that requires intervention?

A: This distinction requires both technical analysis and normative judgment. Technically, examine whether disparities persist after controlling for legitimate factors directly related to your prediction target. Analyze whether measurement validity differs across groups, indicating potential bias in how concepts are operationalized. From a normative perspective, assess whether observed patterns reflect historical inequities that your system should avoid perpetuating, even if statistically predictive. The key determination is whether the statistical patterns represent legitimate predictive signals for your specific task or reflect structural disadvantages that, if encoded in your model, would reproduce or amplify societal inequities.

6. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

Data collection and representation biases form the foundation of fairness issues in AI systems, as biased data inevitably lead to biased models regardless of subsequent interventions. The key concepts from this Unit include:

- Historical bias reflects past prejudices and discriminatory practices in the data, creating a foundation upon which subsequent biases build.

- Sampling bias occurs when data collection results in unrepresentative datasets that systematically disadvantage certain groups.

- Measurement bias emerges from the operationalization of concepts into measurable features in ways that embed unfair assumptions.

- Feature representation bias results from encoding and transformation choices that can amplify disparities across groups.

These concepts directly address our guiding questions by explaining how seemingly technical data decisions can embed bias and by providing systematic approaches to identify these issues before model development begins.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Begin any new ML project with a comprehensive data bias audit before model development.

- Document data collection processes, sampling procedures, and representation statistics as standard practice.

- Validate measurement approaches and feature encodings across demographic groups when demographic data are available.

- Implement bias mitigation strategies at the data level first, before attempting algorithmic interventions.

For organizations new to fairness considerations, start by focusing on basic representation analysis and documentation of data collection processes, then progressively incorporate more sophisticated analyses of measurement and encoding biases as capabilities mature.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will build on this foundation by examining algorithm design and implementation biases—the ways that modeling choices can introduce or amplify unfairness even with perfectly balanced data. You will learn how different learning algorithms, optimization objectives, and hyperparameter choices can create fairness issues, and how to identify these algorithmic bias sources systematically.

The data-level biases we have examined here often interact with algorithmic choices to create complex fairness challenges that neither data interventions nor algorithmic modifications alone can fully address. Understanding both components and their interactions is essential for developing truly effective fairness strategies.

References

Barocas, S., Hardt, M., & Narayanan, A. (2019). Fairness and machine learning: Limitations and opportunities. https://fairmlbook.org

Bolukbasi, T., Chang, K. W., Zou, J. Y., Saligrama, V., & Kalai, A. T. (2016). Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? Debiasing word embeddings. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 4349–4357). https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2016/file/a486cd07e4ac3d270571622f4f316ec5-Paper.pdf

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 77–91). https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

Larson, J., Mattu, S., Kirchner, L., & Angwin, J. (2016). How we analyzed the COMPAS recidivism algorithm. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-analyzed-the-compas-recidivism-algorithm

Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

Wilson, B., Hoffman, J., & Morgenstern, J. (2019). Predictive inequity in object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.11097. https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.11097

Unit 2

Unit 2: Algorithm Design and Implementation Biases

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How do algorithmic design choices and implementation decisions encode or amplify biases, even when using seemingly balanced training data?

- Question 2: What systematic approaches can you implement to identify and mitigate bias introduced through model architecture, optimization objectives, and hyperparameter choices?

Conceptual Context

While data biases often receive primary attention in fairness discussions, the algorithms that process this data introduce their own significant sources of bias. Even with perfectly balanced training data, the choices you make about model architecture, optimization objectives, loss functions, and hyperparameters can create or amplify unfairness through purely algorithmic mechanisms.

These algorithm design biases are particularly insidious because they often appear as technical implementation details rather than explicit fairness concerns. Decisions about which model architecture to use, how to define your loss function, or what regularization approach to apply can embed assumptions that systematically advantage certain groups over others without explicit intention. As Hooker (2021) demonstrated in her analysis of model compression techniques, seemingly neutral efficiency improvements like pruning can disproportionately impact performance on underrepresented groups, creating disparate outcomes through purely algorithmic mechanisms (Hooker, 2021).

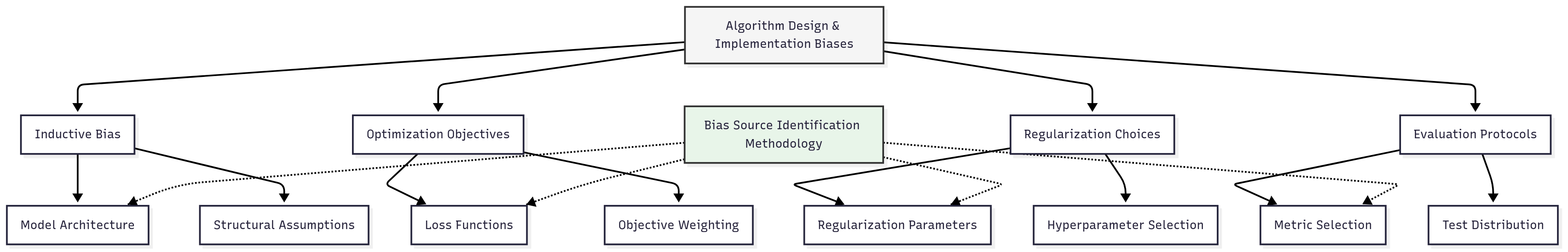

This Unit builds directly on the data collection and representation biases examined in Unit 1, showing how algorithmic choices can compound or sometimes mitigate these earlier biases. It also establishes essential foundations for understanding feedback loops and amplification effects that we'll explore in Unit 3. The insights you develop here will directly inform the Bias Source Identification Methodology we will develop in Unit 5, particularly in identifying algorithm-level entry points where bias can infiltrate ML systems.

2. Key Concepts

Inductive Bias and Model Architecture Selection

Inductive bias—the set of assumptions that a learning algorithm uses to generalize from limited data—significantly influences how models perform across different population groups. This concept is fundamental to AI fairness because different model architectures encode different assumptions about how features relate to outcomes, which can align better with patterns in majority groups than in minority ones.

Inductive bias interacts with data representation biases by determining how effectively models can learn from limited or skewed representations of minority groups. The same dataset processed through different model architectures may produce varying levels of fairness based on how well each architecture's inductive biases align with underlying patterns for different groups.

Research by Urbanek et al. (2019) demonstrated how different model architectures processing identical datasets produced varying levels of gender bias in natural language processing tasks. Their work revealed that transformer-based models, recurrent neural networks, and convolutional architectures each encoded different patterns of gender associations despite training on the same text corpus, showing how architectural choices alone can influence fairness outcomes (Urbanek et al., 2019).

For the Bias Source Identification Methodology we'll develop in Unit 5, understanding inductive bias will be essential for determining how different model architectures might interact with other bias sources. This understanding enables more precise identification of where in the ML pipeline fairness issues originate and which interventions might be most effective.

The key insight is that model architectures are not neutral technical choices but rather encode specific assumptions that may work better for some groups than others. For instance:

- Linear models assume relationships between features and outcomes are linear, which may hold better for majority patterns with more training examples.

- Tree-based methods segment the feature space in ways that might create lower-quality splits for underrepresented groups with fewer samples.

- Deep learning architectures make implicit assumptions about data structure through their connectivity patterns, which might align differently with patterns in different demographic groups.

Optimization Objectives and Loss Functions

Optimization objectives and loss functions directly shape what models learn by defining what constitutes "good" performance. This concept is critical for AI fairness because standard objectives that maximize aggregate performance metrics often implicitly prioritize accuracy on majority groups at the expense of minority group performance.

These objectives interact with inductive bias by guiding how models leverage their architectural capabilities during learning. Together, they determine which patterns receive attention during optimization and which might be ignored as statistically insignificant despite their importance for minority groups.

Hashimoto et al. (2018) demonstrated how standard empirical risk minimization can lead to "representation disparity," where models progressively perform worse on minority groups as training proceeds. Their work showed that even when minority examples are present in training data, models optimized for average performance naturally focus on majority patterns that contribute more to the overall loss, gradually amplifying initial performance disparities (Hashimoto et al., 2018).

For our Bias Source Identification Methodology, understanding how optimization objectives contribute to bias will guide the development of systematic tests to identify whether performance disparities stem from loss function design rather than data issues or architectural limitations. This distinction is crucial for selecting appropriate mitigation strategies.

Standard loss functions that can introduce bias include:

- Mean squared error and cross-entropy loss: By averaging across all examples, these common losses implicitly weight majority group patterns more heavily.

- Accuracy maximization: Objectives that maximize overall accuracy can sacrifice minority group performance when these groups constitute a small percentage of the dataset.

- Proxy objectives: When direct optimization of target metrics is difficult, proxy objectives may correlate differently with desired outcomes across demographic groups.

Regularization and Hyperparameter Choices

Regularization approaches and hyperparameter selections, often viewed as purely technical tuning decisions, can significantly impact fairness by influencing which patterns models extract from data. This concept matters for AI fairness because these choices affect how models balance simplicity against fidelity to training data, which has disparate impacts across demographic groups.

Regularization interacts with both inductive bias and optimization objectives by constraining how models can leverage their architectural capabilities during learning and by shifting the balance between different components of the objective function. These interactions create complex patterns of advantage and disadvantage that standard hyperparameter tuning processes rarely consider.

Research by Kleinberg et al. (2018) illustrated how regularization can have disparate impacts across groups. Their analysis showed that L1 regularization, which promotes sparsity, often eliminates features that are predictive for minority groups but contribute less to overall model performance. Similarly, early stopping, a form of implicit regularization, can freeze models at points where majority group performance has converged but minority group performance is still improving (Kleinberg et al., 2018).

For the Bias Source Identification Methodology, understanding regularization impacts will help develop test cases that isolate how hyperparameter choices might contribute to observed disparities. This analysis can distinguish bias introduced during regularization from issues stemming from data or model architecture.

Common hyperparameter choices with fairness implications include:

- Regularization strength parameters (e.g., λ in L1/L2 regularization): Stronger regularization may disproportionately eliminate features important for minority groups.

- Learning rates and schedules: Different learning dynamics for majority versus minority patterns can make optimization path-dependent in ways that affect fairness.

- Model capacity parameters (e.g., tree depth, network width/depth): Capacity constraints may limit a model's ability to learn complex patterns specific to minority groups.

- Early stopping criteria: Stopping optimization based on aggregate metrics can halt training before minority group performance converges.

Evaluation Protocol Design

Evaluation protocol design—how models are tested, which metrics are prioritized, and how results are interpreted—significantly influences which fairness issues are detected and addressed. This concept is fundamental to AI fairness because evaluation choices determine which disparities become visible to practitioners and which remain hidden.

Evaluation protocols interact with all previously discussed algorithmic choices by determining how we measure their effects. Without appropriate evaluation across demographic groups, biases introduced through architecture, optimization, or regularization choices may go undetected despite significant impacts on minority groups.

Larson et al. (2017) demonstrated the importance of evaluation design in their analysis of natural language processing benchmarks. They showed how standard evaluation metrics often failed to capture performance disparities across demographic groups, creating an illusion of equal progress when improvements actually benefited some populations more than others. Their work emphasized the need for disaggregated evaluation protocols that explicitly assess performance across different demographic groups and intersections (Larson et al., 2017).

For our Bias Source Identification Methodology, understanding evaluation bias will guide the development of testing protocols that can detect algorithmic fairness issues even when they're not explicitly being sought. This awareness ensures that bias identification processes don't inherit the same blind spots as the systems they're designed to evaluate.

Key elements of evaluation protocols with fairness implications include:

- Test set composition: How representative testing data is across demographic groups directly affects which disparities become visible.

- Metric selection: Different evaluation metrics may highlight or obscure fairness issues based on what aspects of performance they measure.

- Significance testing: Statistical approaches for determining whether performance differences are meaningful may be underpowered for minority groups with fewer samples.

- Slice analysis: Whether evaluation examines performance on specific population subgroups or only in aggregate directly affects fairness visibility.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, algorithm design and implementation biases map to specific components of ML systems:

- Model Architecture Selection: How structural choices about model type and connectivity encode assumptions about data relationships.

- Loss Function Design: How performance objectives mathematically define what the model should optimize for.

- Regularization Framework: How constraints on model complexity influence which patterns are learned versus ignored.

- Hyperparameter Configuration: How technical tuning parameters balance various aspects of model behavior.

- Evaluation Infrastructure: How testing protocols and metrics assess performance across different population groups.

This domain mapping helps you systematically analyze how algorithmic choices at different stages of model development might introduce or amplify bias. The Bias Source Identification Methodology will leverage this mapping to create structured approaches for identifying algorithm-level bias sources throughout the development workflow.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract algorithmic concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Inductive bias in model architectures functions like different grading rubrics teachers might use. Just as a rubric focused on multiple-choice questions versus one emphasizing essays would advantage students with different strengths, different model architectures naturally perform better on patterns that align with their structural assumptions. A linear model is like a rubric that only rewards simple, direct relationships, while a deep neural network is like a complex rubric that can reward intricate patterns—but might be applied inconsistently to unfamiliar cases.

- Optimization objectives and loss functions are similar to key performance indicators (KPIs) in business. When a company optimizes exclusively for a metric like total revenue, it might neglect smaller market segments that contribute little to the overall number despite their strategic importance. Similarly, when models optimize for aggregate performance metrics, they naturally focus on patterns common in majority groups that contribute more to the total loss, potentially underserving minority groups even when this creates significant relative disparities.

- Regularization and hyperparameter tuning resemble editorial policy in newspaper coverage. Just as editorial choices about article length and complexity affect which stories can be adequately covered (often disadvantaging complex issues affecting minority communities), regularization affects which patterns models can learn (often disadvantaging complex minority group patterns). Stronger regularization is like stricter word count limits—it may disproportionately constrain coverage of stories requiring nuanced explanation, just as it may eliminate features particularly important for understanding minority group patterns.

Intersectionality Consideration

Algorithm design biases present unique challenges for intersectional fairness, where multiple protected attributes interact to create distinct patterns that affect individuals with overlapping marginalized identities. Models optimized for aggregate performance or even single-attribute fairness may still perform poorly on intersectional subgroups due to both data limitations and algorithmic mechanisms.

As demonstrated by Kearns et al. (2018) in their work on "fairness gerrymandering," algorithms can satisfy fairness constraints with respect to individual protected attributes while still discriminating against specific intersectional subgroups. Their research showed that standard approaches to algorithmic fairness often failed to protect individuals at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities, revealing the need for explicitly intersectional fairness formulations (Kearns et al., 2018).

Addressing intersectional considerations in algorithm design requires:

- Model architectures that can effectively learn from smaller intersectional subgroups despite limited samples;

- Loss functions that balance performance across both high-level groups and their intersections;

- Regularization approaches that preserve important features for intersectional subgroups despite their statistical minority status; and

- Evaluation protocols that explicitly assess performance across demographic intersections, not just along individual protected attributes.

The Bias Source Identification Methodology must incorporate these intersectional considerations by developing analysis approaches that systematically examine algorithm performance across demographic intersections, even when these groups constitute small minorities in the dataset.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To systematically identify and address algorithm-level biases, implement the following structured methodology:

-

Model Architecture Analysis:

-

Examine how different model architectures perform across demographic groups with the same training data.

- Analyze whether architectural assumptions align with patterns present in minority groups.

- Test whether increasing model capacity differentially improves performance across groups.

-

Document architecture-specific fairness implications to inform selection decisions.

-

Loss Function Evaluation:

-

Decompose performance metrics by demographic group to identify disparate optimization patterns.

- Analyze convergence trajectories to determine whether minority group performance plateaus later than majority groups.

- Test modified loss functions that give equal weight to examples regardless of group size.

-

Implement group-aware losses that explicitly balance performance across demographic categories.

-

Regularization Impact Assessment:

-

Compare feature importance across demographic groups before and after regularization.

- Analyze how different regularization parameters affect performance disparities.

- Implement group-specific regularization to account for different sample sizes.

-

Document how early stopping points affect the fairness-performance frontier.

-

Evaluation Protocol Design:

-

Implement disaggregated evaluation that examines performance across both protected attributes and their intersections.

- Develop statistical approaches appropriate for different group sizes.

- Create performance dashboards that highlight disparities across multiple metrics.

- Establish minimum performance thresholds for all demographic groups rather than just in aggregate.

These methodologies integrate with standard ML workflows by extending model selection, optimization, and evaluation processes to explicitly incorporate fairness considerations. While they add analytical complexity, they leverage many existing practices while orienting them toward detecting and addressing algorithmic sources of bias.

Implementation Challenges

When implementing these approaches, practitioners commonly encounter the following challenges:

-

Performance-Fairness Trade-offs: More complex architectures or fairness-aware losses may reduce aggregate performance. Address this by:

-

Developing clear documentation of trade-off frontiers to inform stakeholder discussions;

- Implementing multi-objective optimization approaches that explicitly balance competing goals; and

-

Creating evaluation frameworks that assess both standard performance and fairness metrics in context.

-

Limited Samples for Algorithmic Analysis: Some demographic groups may have too few examples to reliably assess algorithmic impacts. Address this by:

-

Implementing synthetic data approaches to test algorithmic behavior under controlled conditions;

- Using transfer learning from related domains with more balanced data to isolate algorithmic effects; and

- Applying statistical techniques specifically designed for small sample inference.

Successfully implementing algorithm bias analysis requires computational resources for testing multiple model configurations, expertise in both machine learning and fairness evaluation, and organizational willingness to potentially sacrifice some aggregate performance for more equitable outcomes across groups.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your algorithm bias identification and mitigation approaches are effective, implement these evaluation strategies:

-

Architecture Fairness Assessment:

-

Calculate performance disparities across demographic groups for different model architectures using identical training data.

- Establish acceptable disparity thresholds based on domain-specific requirements.

-

Compare disparities before and after architecture modifications to quantify improvements.

-

Optimization Fairness Metrics:

-

Track performance trajectories by demographic group throughout training.

- Measure whether loss reductions are balanced across groups or concentrated in majority populations.

-

Evaluate whether fairness-aware losses reduce disparities compared to standard objectives.

-

Regularization Equity Analysis:

-

Assess whether regularization disproportionately affects features important to specific demographic groups.

- Compare performance disparities across different regularization strategies and parameters.

- Measure the impact of custom regularization approaches designed to preserve minority group features.

These metrics should be integrated with your organization's broader fairness assessment framework, providing inputs to comprehensive bias source identification processes that span the entire ML lifecycle.

4. Case Study: Content Recommendation System

Scenario Context

A digital media company is developing a content recommendation algorithm to personalize article suggestions for users on their news platform. The system analyzes user behavior, content characteristics, and contextual factors to predict engagement likelihood. Key stakeholders include product managers focused on increasing overall engagement, editorial teams concerned about content diversity, users from various demographic backgrounds seeking relevant information, and business leaders monitoring revenue implications.

Fairness is particularly critical in this context because recommendation algorithms shape information access, potentially creating filter bubbles or unequal access to opportunities based on user demographics. The company wants to ensure their algorithm provides high-quality recommendations to all user groups while maintaining strong overall engagement metrics.

Problem Analysis

Applying core concepts from this Unit reveals several potential algorithm-level biases in the recommendation system scenario:

- Inductive Bias and Architecture: Initial testing revealed that the matrix factorization architecture initially selected for the recommendation system created larger performance gaps across demographic groups than a graph neural network architecture using identical training data. Analysis showed that matrix factorization's linear embedding assumptions worked well for users with extensive interaction histories (predominantly from majority demographic groups) but struggled with users having sparse interaction patterns (more common among minority users and new users from all demographics).

- Optimization Objectives: The team had initially defined their loss function to maximize click-through rate (CTR) across all recommendations. Disaggregated analysis revealed this objective led to progressively worsening recommendations for minority groups during training, as the model focused on patterns that improved majority group engagement at the expense of minority group experience. While overall CTR improved, the disparity between demographic groups increased by 45% after optimization.

- Regularization Effects: Standard L2 regularization applied to control overfitting had disproportionate effects across user groups. Stronger regularization improved performance for majority groups by preventing overfitting to noise, but simultaneously eliminated subtle but important patterns for minority groups where limited data made legitimate signals statistically similar to noise. This created an implicit trade-off where regularization strength that was optimal for majority groups systematically underserved minority users.

- Evaluation Protocol Issues: The standard A/B testing framework evaluated new algorithm versions based on aggregate engagement metrics without disaggregation by demographic groups. This approach had repeatedly approved algorithm changes that improved overall metrics while degrading the experience for specific user segments, as improvements for majority users outweighed regressions for minority groups in aggregate statistics.

From an intersectional perspective, the most severe performance disparities affected users at specific demographic intersections—for instance, older users from minority racial backgrounds showed recommendation quality significantly worse than would be predicted by examining either age or racial factors independently.

Solution Implementation

To address these identified algorithm-level biases, the team implemented a structured approach:

-

For Architecture Bias, they:

-

Conducted a systematic comparison of different architectures including matrix factorization, factorization machines, and graph neural networks;

- Selected a hybrid architecture combining the strengths of multiple approaches to better serve diverse user interaction patterns; and

-

Implemented separate embedding dimensions for different user segments to account for varying data density and pattern complexity.

-

For Optimization Objectives, they:

-

Redesigned their loss function to explicitly balance performance across demographic groups;

- Implemented a multi-objective approach that considered both overall engagement and equity across groups; and

-

Added constraints to ensure minimum quality standards for all user segments regardless of size.

-

For Regularization Impacts, they:

-

Implemented adaptive regularization that adjusted strength based on data quantity for different user groups;

- Created feature importance preservation mechanisms to maintain predictive patterns for minority groups despite limited statistical power; and

-

Designed custom early stopping criteria that monitored convergence across demographic segments rather than just in aggregate.

-

For Evaluation Protocols, they:

-

Redesigned their testing framework to automatically disaggregate results across demographic dimensions;

- Implemented statistical tests appropriate for different sample sizes across groups; and

- Created fairness-specific dashboards highlighting disparities alongside traditional performance metrics.

Throughout implementation, they maintained explicit focus on intersectional effects, ensuring that their algorithmic improvements addressed the specific challenges faced by users at the intersection of multiple demographic factors.

Outcomes and Lessons

The implementation resulted in significant improvements across multiple dimensions:

- The hybrid architecture reduced performance disparities across demographic groups by 62% while maintaining strong overall engagement metrics.

- The revised loss function prevented the progressive degradation of minority group recommendations during training.

- Adaptive regularization preserved important features for minority groups that standard approaches would have eliminated.

- The new evaluation framework successfully identified and prevented changes that would have created disparate impacts despite improving aggregate metrics.

Key challenges remained, including tensions between different fairness objectives and the computational complexity of more sophisticated architectural approaches.

The most generalizable lessons included:

- The critical importance of testing multiple model architectures with identical data to isolate purely algorithmic sources of bias.

- The significant impact of loss function design on how models balance performance across different user groups during optimization.

- The need for regularization approaches that account for different data characteristics across demographic groups rather than applying uniform constraints.

These insights directly informed the development of the Bias Source Identification Methodology, particularly in creating systematic tests to distinguish algorithm-level biases from data issues and in establishing appropriate evaluation approaches for different bias sources.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Distinguishing Algorithm Bias From Data Bias

Q: How can I determine whether observed fairness disparities stem from algorithm design choices rather than biases in the training data?

A: Isolate algorithmic effects by systematically varying model components while keeping training data constant. Compare performance disparities across different architectures, optimization objectives, and regularization approaches using identical datasets. If disparities change significantly based on algorithmic choices alone, this indicates algorithm-level bias contributions. Additionally, create synthetic experiments where you introduce controlled biases into otherwise balanced data to measure how different algorithms respond to known data issues. Track how performance disparities evolve during training—if gaps increase during optimization despite balanced initial predictions, this suggests the optimization process itself is amplifying minor initial differences. Finally, analyze feature importance across demographic groups before and after training to determine whether the algorithm systematically undervalues features important for minority groups.

FAQ 2: Fairness-Performance Trade-offs in Algorithm Design

Q: When more complex or fairness-aware algorithms reduce overall performance metrics, how should I navigate these trade-offs with stakeholders?

A: First, quantify the exact nature of the trade-offs by mapping the Pareto frontier showing potential operating points balancing performance and fairness. This transforms an abstract discussion into a concrete decision about where on this frontier the organization wishes to operate. Frame fairness not as a constraint on performance but as an additional quality dimension, similar to how robustness or interpretability might be considered alongside accuracy. Connect fairness considerations to specific business risks—including legal liability, reputational damage, and lost market opportunities in underserved segments—to contextualize short-term metric impacts. Develop disaggregated metrics that show both overall performance and performance for specific groups, making disparities explicit rather than hidden in aggregates. Finally, propose incremental adoption approaches that gradually improve fairness while managing performance impacts through controlled deployment.

6. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

Algorithmic design and implementation choices introduce distinct sources of bias beyond any issues present in the training data. The key concepts from this Unit include:

- Inductive bias in model architectures influences which patterns models can effectively learn, potentially creating disparate performance when architectural assumptions align better with majority group patterns than minority ones.

- Optimization objectives and loss functions shape how models balance performance across groups during training, often implicitly prioritizing majority group patterns that contribute more to aggregate metrics.

- Regularization and hyperparameter choices affect which features and patterns are preserved versus eliminated, potentially disadvantaging minority groups with limited samples or complex predictive patterns.

- Evaluation protocol design determines which disparities become visible during testing, with standard approaches often obscuring performance issues affecting specific demographic groups.

These concepts directly address our guiding questions by explaining how algorithmic choices encode or amplify biases even with balanced data and by providing systematic approaches to identify and mitigate these purely algorithmic sources of unfairness.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Test multiple model architectures with identical training data to isolate architecture-specific fairness effects.

- Decompose loss function optimization by demographic group to identify disparate convergence patterns.

- Analyze the impact of regularization and hyperparameters on different demographic groups rather than just on aggregate performance.

- Implement disaggregated evaluation protocols that assess performance across both individual protected attributes and their intersections.

For organizations new to algorithmic fairness considerations, start by implementing basic disaggregated evaluation across demographic groups for your existing models. This baseline analysis will help identify where disparities exist, allowing you to progressively implement more sophisticated architecture comparisons, loss function analyses, and regularization assessments as your capabilities mature.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will build on this foundation by examining feedback loops and amplification effects that can magnify initial biases over time. You will learn how model outputs influence future data collection, how algorithmic decisions can create reinforcing cycles of disadvantage, and how to identify systems at high risk for runaway bias amplification.

The algorithm-level biases we have examined here often serve as the initial seeds for these feedback effects, with small algorithmic disparities potentially growing into significant fairness issues through repeated application and data recollection. Understanding both static algorithmic biases and dynamic feedback effects is essential for developing comprehensive fairness strategies that remain effective over time.

References

Hashimoto, T. B., Srivastava, M., Namkoong, H., & Liang, P. (2018). Fairness without demographics in repeated loss minimization. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 1929-1938). http://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/hashimoto18a.html

Hooker, S. (2021). Moving beyond "algorithmic bias is a data problem". Patterns, 2(4), 100241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2021.100241

Kearns, M., Neel, S., Roth, A., & Wu, Z. S. (2018). Preventing fairness gerrymandering: Auditing and learning for subgroup fairness. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 2564-2572). http://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/kearns18a.html

Kleinberg, J., Ludwig, J., Mullainathan, S., & Rambachan, A. (2018). Algorithmic fairness. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108, 22-27. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20181018

Larson, J., Mattu, S., Kirchner, L., & Angwin, J. (2017). How we analyzed the COMPAS recidivism algorithm. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-analyzed-the-compas-recidivism-algorithm

Urbanek, J., Kannan, A., Kamath, A., Lobez, J. I., & DeFour, M. (2019). Comparing model architectures for NLP fairness. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.01485. https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.01485

Unit 3

Unit 3: Feedback Loops and Amplification Effects

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How do feedback loops in AI systems transform initial biases into progressively larger disparities over time?

- Question 2: What technical mechanisms can data scientists implement to detect, measure, and interrupt harmful feedback dynamics before they create significant fairness violations?

Conceptual Context

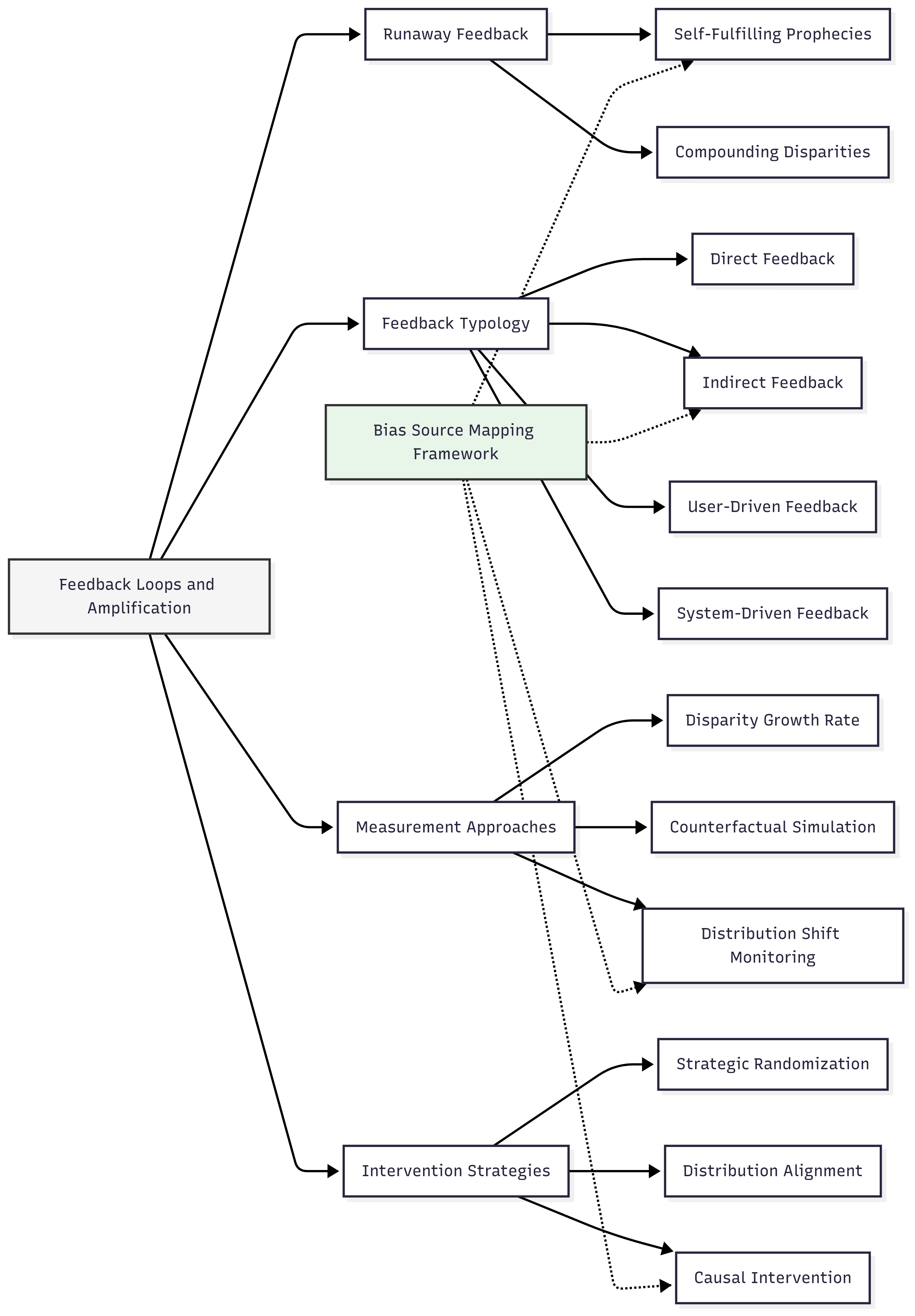

Feedback loops represent one of the most pernicious mechanisms through which initially small biases can transform into significant fairness problems in AI systems. While static bias sources in data or algorithms create constant disparities, feedback dynamics can generate exponentially growing disparities as systems influence the environments they observe, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of inequity.

These feedback mechanisms are particularly dangerous because they often operate invisibly, with seemingly minor initial disparities compounding over time through multiple iterations of model deployment and data collection. As Ensign et al. (2018) demonstrate in their analysis of predictive policing algorithms, feedback loops can create a "runaway" effect where the model's own predictions shape future data in ways that confirm and amplify initial biases, regardless of underlying ground truth (Ensign et al., 2018).

This Unit builds directly on the data collection and representation biases explored in Units 1-2 by examining how these initial biases can be magnified through system dynamics rather than remaining static. It establishes essential foundations for understanding deployment biases in Unit 4 by focusing on the iterative processes through which models interact with their environments over time. The insights you develop here will directly inform the Bias Source Identification Tool in Unit 5, particularly in identifying dynamic bias sources that emerge through system operation rather than existing in any single component.

2. Key Concepts

Runaway Feedback Effects

Runaway feedback effects occur when an AI system's predictions influence future data collection in ways that systematically reinforce and amplify the system's existing patterns, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy that progressively diverges from ground truth. This concept is crucial for AI fairness because these self-reinforcing cycles can transform small initial biases into significant disparities over time, often operating invisibly until substantial harm has occurred.

Runaway feedback connects directly to data bias concepts from previous Units, showing how representation disparities can become progressively worse through system operation rather than remaining static. This dynamic view complements the static analysis of bias sources by revealing how initial biases evolve over time.

Research by Ensign et al. (2018) provides a powerful application example in predictive policing, demonstrating mathematically how these algorithms can create feedback loops that reinforce initial biases. Their study showed that when police are dispatched based on predictions from historical arrest data, new arrests occur disproportionately in already over-policed neighborhoods. These new arrests then enter the historical data, strengthening the pattern that led to their prediction and creating a self-reinforcing cycle disconnected from actual crime rates (Ensign et al., 2018).

Similar dynamics appear in content recommendation systems, where initial disparities in content exposure lead to differential engagement patterns, which then inform future recommendations in a reinforcing cycle. For example, an educational content recommendation system showing slight initial bias toward traditionally "male" subjects for boys and "female" subjects for girls will collect engagement data shaped by these initial recommendations, potentially creating increasingly gender-stereotyped content exposure over time.

For the Bias Source Identification Tool we will develop, understanding runaway feedback effects helps identify dynamic bias sources that emerge through system operation rather than existing in static components. This perspective guides the development of monitoring approaches that track disparity growth over time rather than just measuring bias at a single point.

Feedback Loop Typology

Feedback loops in AI systems can be categorized into distinct types based on their operational mechanisms, information flows, and fairness implications. Understanding this typology is essential for AI fairness because different feedback types require specific detection and mitigation approaches tailored to their particular dynamics.

This typology interacts with runaway feedback effects by providing a structured framework for analyzing how different feedback mechanisms lead to bias amplification. It also connects to subsequent concepts by identifying specific points where monitoring or intervention might be most effective.

As established by Mansoury et al. (2020) in their analysis of recommendation systems, we can distinguish between several feedback types:

- Direct Feedback Loops occur when a system's outputs directly influence future inputs in the same decision stream. For example, a content recommendation algorithm suggesting certain items leads to user engagement with those items, which then reinforces those recommendation patterns.

- Indirect Feedback Loops involve a system's outputs influencing future inputs through intermediate mechanisms or external systems. For instance, an automated resume screening tool might influence which candidates receive interview training, affecting their performance in future application processes.

- User-Driven Feedback emerges from how users interact with and adapt to an AI system over time. For example, users may learn to use specific keywords to achieve desired outcomes from search algorithms, creating distribution shifts that affect system performance.

- System-Driven Feedback occurs when the AI system itself evolves in response to new data without explicit user adaptation. For instance, continual learning systems that automatically update based on new observations can develop increasingly biased patterns without direct user input.

Understanding these distinct feedback mechanisms is critical for effective bias mitigation. For example, mitigating direct feedback loops might involve randomization techniques to break self-reinforcing cycles, while addressing user-driven feedback requires monitoring for strategic adaptation patterns across different user groups.

For our Bias Source Identification Tool, this typology will guide the development of specific detection techniques for different feedback mechanisms, ensuring comprehensive coverage of dynamic bias sources across system types.

Measurement and Detection Approaches

Detecting and measuring feedback-induced bias amplification requires specialized techniques beyond static fairness metrics, as the key concern is how disparities evolve over time rather than their magnitude at any specific moment. These measurement approaches are essential for AI fairness because they enable early detection of potentially harmful feedback dynamics before they create significant disparities.

Measurement approaches connect to the feedback typology by providing specific techniques for quantifying different feedback mechanisms. They also establish the foundation for intervention strategies by identifying when and how to interrupt harmful feedback cycles.

Research by Hashimoto et al. (2018) demonstrates several approaches for measuring feedback-induced disparities, including:

- Disparity Growth Rate Analysis tracks the change in fairness metrics over multiple system iterations, focusing on the rate of change rather than absolute values. This approach can detect exponential growth patterns characteristic of runaway feedback.

- Counterfactual Simulation involves running simulations with and without feedback mechanisms to isolate their specific effects on different groups. These simulations can reveal how initially small disparities might evolve under continued system operation.

- Distribution Shift Monitoring examines how input data distributions change over time in response to system outputs, with particular attention to whether these shifts differ across demographic groups.

- Causal Analysis of Feedback Paths identifies and quantifies specific causal mechanisms through which system outputs influence future inputs, often using intervention experiments that deliberately break potential feedback paths.

As Hashimoto et al. (2018) demonstrated in their analysis of natural language processing systems, these measurement approaches can reveal "performative prediction" effects where model outputs influence future data in ways that create increasingly biased patterns over time. Their research showed how initially minor representation disparities in language models progressively worsen through feedback dynamics, as underrepresented groups receive worse model performance, potentially reducing their system usage and further diminishing their representation in training data (Hashimoto et al., 2018).

For the Bias Source Identification Tool, these measurement approaches will form a critical component for detecting dynamic bias sources that emerge through system operation. The framework will include specific methodologies for implementing these measurements across different AI applications and system architectures.

Intervention Strategies for Breaking Harmful Cycles

Once harmful feedback loops are identified, specific technical interventions can break these cycles before they create significant fairness violations. These intervention strategies are crucial for AI fairness because they provide concrete mechanisms for preventing bias amplification in systems where feedback dynamics are unavoidable.

Intervention strategies build directly on measurement approaches by using detection insights to implement targeted solutions. They represent the actionable component that follows from understanding feedback mechanisms and their potential harms.

Research by D'Amour et al. (2020) and others has established several effective intervention strategies:

- Strategic Randomization introduces controlled randomness into model outputs to prevent self-reinforcing patterns from becoming entrenched. For example, exploration parameters in recommendation systems can ensure diverse content exposure despite initial popularity disparities.

- Periodic Distribution Alignment explicitly corrects for distribution shifts by reweighting or resampling training data to match target distributions, preventing progressive drift due to feedback effects.

- Causal Intervention specifically targets and modifies the causal mechanisms through which system outputs influence future inputs, breaking harmful feedback paths while maintaining beneficial ones.

- Multi-stakeholder Optimization incorporates the welfare of all system participants into the objective function, preventing feedback dynamics that benefit certain groups at others' expense.

D'Amour et al. (2020) demonstrated these approaches in their work on performative prediction, showing how strategic modifications to learning algorithms can prevent harmful feedback cycles in systems ranging from credit scoring to content recommendation. Their research established that simple interventions like periodic retraining with distribution constraints can significantly reduce bias amplification while maintaining overall system performance (D'Amour et al., 2020).

For our Bias Source Identification Tool, these intervention strategies will provide critical guidance on how to address dynamic bias sources once they are detected. The framework will connect specific feedback mechanisms to appropriate intervention approaches, enabling targeted solutions rather than generic fairness constraints.