Context

Quantitative measurement transforms abstract fairness principles into verifiable properties. Without precise metrics, fairness remains aspirational rather than measurable, making systematic improvement impossible.

Different metrics embody distinct fairness perspectives. A lending algorithm optimized for demographic parity (equal approval rates across groups) makes different decisions than one optimized for equal opportunity (equal approval rates for qualified applicants across groups). These metrics directly guide optimization and determine who receives loans, housing, or opportunities.

Statistical challenges complicate fairness evaluation, especially when assessing performance across demographic groups with different sample sizes. Naïve approaches can lead to misleading conclusions, particularly for minority groups with limited representation. Techniques like bootstrapping, Bayesian methods, and appropriate significance testing provide more reliable assessments even with imbalanced data.

Traditional metrics often examine protected attributes independently, missing critical disparities at their intersections. A facial recognition system might show similar accuracy across gender when aggregated by race and similar accuracy across race when aggregated by gender, while still performing significantly worse for specific combinations like women with darker skin tones. Implementation challenges include smaller sample sizes at demographic intersections, increased computational complexity, and visualization difficulties.

Fairness metrics map to ML system components: problem definition (what constitutes fairness), data requirements (necessary attributes), model evaluation (assessment framework), performance trade-offs (fairness-accuracy balance), and monitoring systems (ongoing evaluation).

The Fairness Metrics Tool you'll develop in Unit 5 represents the fourth component of the Fairness Audit Playbook (Sprint Project). This tool will help you select appropriate metrics based on fairness definitions, implement them with statistical rigor, and integrate them into a cohesive evaluation approach.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this Part, you will be able to:

- Implement group fairness metrics for classification and regression tasks. You will translate fairness definitions into mathematical implementations for different problem types, measuring properties across demographic groups and quantifying disparities in model performance.

- Design individual fairness measures based on appropriate similarity functions. You will develop metrics ensuring similar individuals receive similar predictions regardless of protected attributes, addressing fairness concerns that group-level metrics might miss.

- Apply statistical validation techniques to fairness measurements. You will implement confidence interval estimation, significance testing, and robustness checks, distinguishing between statistically significant fairness disparities and random variation.

- Develop intersectional fairness evaluation approaches. You will create methodologies capturing fairness across multiple, overlapping demographic dimensions, identifying disparities affecting specific intersectional groups that single-attribute analyses would miss.

- Design fairness metric tools that balance multiple fairness dimensions. You will create approaches for selecting, implementing, and interpreting multiple fairness metrics within specific application contexts, enabling assessment that acknowledges inherent trade-offs.

Units

Unit 1

Unit 1: Group Fairness Metrics

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How can we quantitatively measure whether ML models treat different demographic groups fairly, and what trade-offs exist between different mathematical formulations of group fairness?

- Question 2: When is each group fairness metric most appropriate for specific application domains, and how do these metrics align with different ethical and legal definitions of fairness?

Conceptual Context

Group fairness metrics form the quantitative foundation for assessing whether machine learning systems exhibit discriminatory behavior across demographic groups. These metrics translate abstract fairness principles into concrete mathematical properties that can be measured, monitored, and optimized during model development and deployment.

The importance of group fairness metrics extends beyond academic concerns—they directly address legal and ethical requirements across regulated domains like lending, hiring, and criminal justice. For instance, the "disparate impact" legal doctrine established in the 1971 Griggs v. Duke Power Co. Supreme Court case requires that practices with disproportionate adverse effects on protected groups must be justified by business necessity. Group fairness metrics provide the statistical framework for detecting such disparate impact and evaluating whether interventions successfully mitigate it.

This Unit builds on the historical and societal foundations established in Part 1, where we explored how bias manifests in AI systems, and the fairness definitions introduced in Part 2, which provided conceptual frameworks for understanding what fairness means in different contexts. Now, we translate those concepts into precise mathematical formulations that enable rigorous evaluation. The metrics you'll learn in this Unit will directly inform the Fairness Metrics Tool you'll develop in Unit 5, providing the mathematical foundation for measuring group-level disparities across different fairness dimensions.

2. Key Concepts

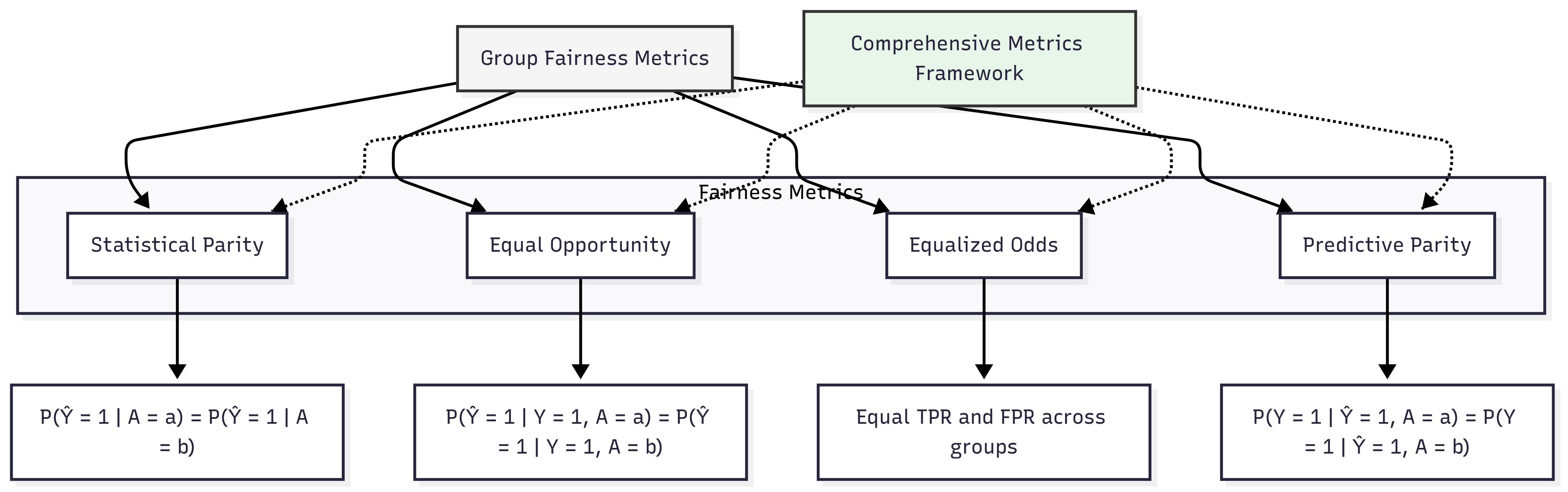

Statistical Parity (Demographic Parity)

Statistical parity requires that the probability of receiving a positive outcome should be equal across all demographic groups, regardless of other attributes. This metric is fundamental to AI fairness because it directly addresses representation disparities in model outputs, ensuring that beneficial predictions (like loan approvals or job interview selections) are distributed equally across protected groups.

Statistical parity interacts with other fairness concepts through inherent tensions. As we'll see when exploring other metrics, it often conflicts with accuracy and individual fairness when base rates (the underlying distribution of positive outcomes) differ between groups. This tension highlights the importance of contextual selection rather than universal application of any single metric.

Mathematically, statistical parity is satisfied when:

P(Ŷ = 1 │ A = a) = P(Ŷ = 1 │ A = b)

where Ŷ represents the model's prediction and A represents the protected attribute. This equation requires that the probability of receiving a positive prediction is equal across all values of the protected attribute.

To quantify violations of statistical parity, we can use the Statistical Parity Difference (SPD):

SPD = │P(Ŷ = 1 │ A = a) - P(Ŷ = 1 │ A = b)│

Research by Feldman et al. (2015) demonstrated how statistical parity can be practically implemented in high-stakes scenarios like employment screening. Their work showed that preprocessing techniques could remove correlations between protected attributes and predictions, effectively enforcing demographic parity while maintaining reasonable predictive power. However, they also highlighted the inherent trade-offs: enforcing perfect demographic parity can sometimes reduce accuracy and may not be appropriate when true base rates differ legitimately between groups.

For the Fairness Metrics Tool we'll develop in Unit 5, statistical parity provides a foundational measure that directly addresses the ethical principle of equal representation in outcomes. It's particularly relevant in contexts like shortlisting job candidates or selecting recipients for limited opportunities, where ensuring demographic balance in outcomes may be a primary fairness objective.

Equal Opportunity (True Positive Rate Parity)

Equal opportunity focuses on ensuring that qualified individuals have similar chances of receiving positive predictions, regardless of their demographic group. This metric requires equal true positive rates across groups, meaning that the probability of individuals who actually deserve a positive outcome (like qualified job applicants) receiving that positive prediction should be the same regardless of protected attributes.

Equal opportunity connects to statistical parity by offering a more nuanced approach that accounts for qualification differences. While statistical parity might approve equal numbers of applicants across groups regardless of qualifications, equal opportunity focuses on giving equally qualified individuals equal chances, potentially allowing for different overall acceptance rates if qualification rates differ between groups.

Mathematically, equal opportunity is satisfied when:

P(Ŷ = 1 │ Y = 1, A = a) = P(Ŷ = 1 │ Y = 1, A = b)

where Y represents the true outcome. This equation requires that the probability of receiving a positive prediction, given that the true outcome is positive, is equal across all values of the protected attribute.

To quantify violations of equal opportunity, we can use the Equal Opportunity Difference (EOD):

EOD = │P(Ŷ = 1 │ Y = 1, A = a) - P(Ŷ = 1 │ Y = 1, A = b)│

Hardt, Price, and Srebro (2016) proposed equal opportunity as a fairness measure that better aligns with anti-discrimination principles in contexts where qualification matters. Their work demonstrated that post-processing techniques could achieve equal true positive rates across groups with minimal accuracy loss. They showed that equal opportunity allows for more flexible and context-appropriate fairness implementations compared to the stricter requirements of demographic parity.

For our Fairness Metrics Tool, equal opportunity provides a crucial measure for contexts where fairness should focus on qualified individuals receiving equal treatment. It's particularly relevant in merit-based selection processes like lending, admissions, or hiring, where the goal is to ensure that qualified individuals have equal chances regardless of protected attributes, rather than enforcing equal representation regardless of qualifications.

Equalized Odds (Error Rate Balance)

Equalized odds extends equal opportunity by requiring balanced false positive rates in addition to balanced true positive rates across groups. This metric ensures that both error types—incorrectly giving positive predictions to negative examples and incorrectly giving negative predictions to positive examples—occur at equal rates across demographic groups.

Equalized odds connects to other fairness metrics by offering one of the most comprehensive forms of error rate balance. It strengthens equal opportunity's requirement for equal true positive rates by adding constraints on false positive rates, addressing concerns about both types of mistakes disproportionately affecting certain groups.

Mathematically, equalized odds is satisfied when:

P(Ŷ = 1 │ Y = y, A = a) = P(Ŷ = 1 │ Y = y, A = b) for y ∈ {0, 1}

This equation requires that the probability of receiving a positive prediction, given any true outcome value, is equal across all values of the protected attribute.

To quantify violations of equalized odds, we can use both true positive rate differences and false positive rate differences across groups:

The seminal work by Hardt, Price, and Srebro (2016) introduced equalized odds alongside equal opportunity, demonstrating how both can be achieved through post-processing techniques. Their research showed that equalized odds provides a stronger fairness guarantee than equal opportunity alone, but at a potentially greater cost to accuracy. This trade-off highlights the need for context-specific selection between these related metrics.

Practical implementations by Chouldechova and G'Sell (2017) in criminal justice risk assessment demonstrated that achieving equalized odds could sometimes lead to unexpected consequences, such as requiring higher thresholds for positive predictions among historically disadvantaged groups—an outcome that might appear counterintuitive but follows mathematically from base rate differences.

For our Fairness Metrics Tool, equalized odds provides a rigorous standard for contexts where both false positives and false negatives have significant consequences for affected individuals. It's particularly relevant in high-stakes decision systems like criminal justice risk assessment, medical diagnosis, or fraud detection, where both types of errors can cause serious harm and should be balanced across groups.

Predictive Parity (Positive Predictive Value Parity)

Predictive parity focuses on ensuring that positive predictions have the same precision across different demographic groups. This metric requires that when a model predicts a positive outcome for individuals from different groups, those predictions should be equally reliable—meaning they correspond to actual positive outcomes at similar rates.

Predictive parity connects to error rate metrics like equal opportunity and equalized odds but focuses on a different aspect of model performance. While those metrics examine recall (what proportion of true positives are correctly identified), predictive parity examines precision (what proportion of positive predictions are correct). This distinction creates an important complementary perspective on fairness.

Mathematically, predictive parity is satisfied when:

P(Y = 1 │ Ŷ = 1, A = a) = P(Y = 1 │ Ŷ = 1, A = b)

This equation requires that the probability of the true outcome being positive, given a positive prediction, is equal across all values of the protected attribute.

To quantify violations of predictive parity, we can use the Predictive Parity Difference (PPD):

PPD = │P(Y = 1 │ Ŷ = 1, A = a) - P(Y = 1 │ Ŷ = 1, A = b)│

Chouldechova (2017) demonstrated a fundamental impossibility result related to predictive parity: when base rates differ between groups, it is mathematically impossible to simultaneously achieve predictive parity, equal false positive rates, and equal false negative rates. This result, along with similar findings by Kleinberg et al. (2016), establishes the inherent trade-offs between different fairness metrics and the necessity of context-dependent choices.

For our Fairness Metrics Tool, predictive parity provides an essential measure for contexts where the reliability of positive predictions across groups is a primary concern. It's particularly relevant in risk assessment contexts like credit scoring or disease diagnosis, where practitioners need confidence that positive predictions have consistent meaning across demographic groups.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, group fairness metrics map to different components of ML systems:

- Input Processing: Statistical parity focuses on the relationship between protected attributes and predictions, requiring independence.

- Error Analysis: Equal opportunity and equalized odds examine errors conditionally on true outcomes, targeting specific error types.

- Prediction Interpretation: Predictive parity addresses how predictions should be interpreted, ensuring consistent meaning across groups.

- Decision Thresholds: All metrics influence threshold selection, often requiring group-specific thresholds to satisfy fairness constraints.

- Monitoring Systems: These metrics form the foundation for ongoing fairness monitoring in deployed systems, tracking disparities over time.

This domain mapping helps you understand how fairness metrics connect to specific components of ML systems rather than viewing them as abstract mathematical formulas. The Fairness Metrics Tool will leverage this mapping to guide appropriate metric selection and implementation based on where in the ML pipeline fairness concerns are most critical.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract mathematical concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Statistical parity is similar to a university's admissions policy that aims to admit equal percentages of applicants from different demographic groups. Just as this policy focuses on the outcome distribution regardless of other factors, statistical parity ensures that beneficial predictions are distributed equally across groups, regardless of other attributes. The key insight is that this approach prioritizes representation in outcomes, potentially at the expense of individual merit considerations.

- Equal opportunity resembles a hiring policy that ensures equally qualified candidates have equal chances of receiving interview invitations, regardless of background. The policy acknowledges that qualification rates might differ between groups but insists that qualified individuals should have equal chances. Similarly, equal opportunity in ML ensures that individuals who truly deserve positive outcomes have equal chances of receiving positive predictions, regardless of their demographic group.

- Equalized odds functions like a comprehensive error-balancing policy that ensures both false alarms and missed detections occur at similar rates across groups. Imagine a security screening system at airports: equalized odds would require that both incorrect flagging of innocent travelers and missed detection of actual threats occur at similar rates across demographic groups, preventing both types of errors from disproportionately affecting certain populations.

- Predictive parity is analogous to ensuring that a test for a medical condition has the same reliability across different patient populations. When the test returns a positive result, doctors should have the same confidence in that result regardless of the patient's demographic background. Similarly, predictive parity ensures that positive predictions have consistent meaning and reliability across groups.

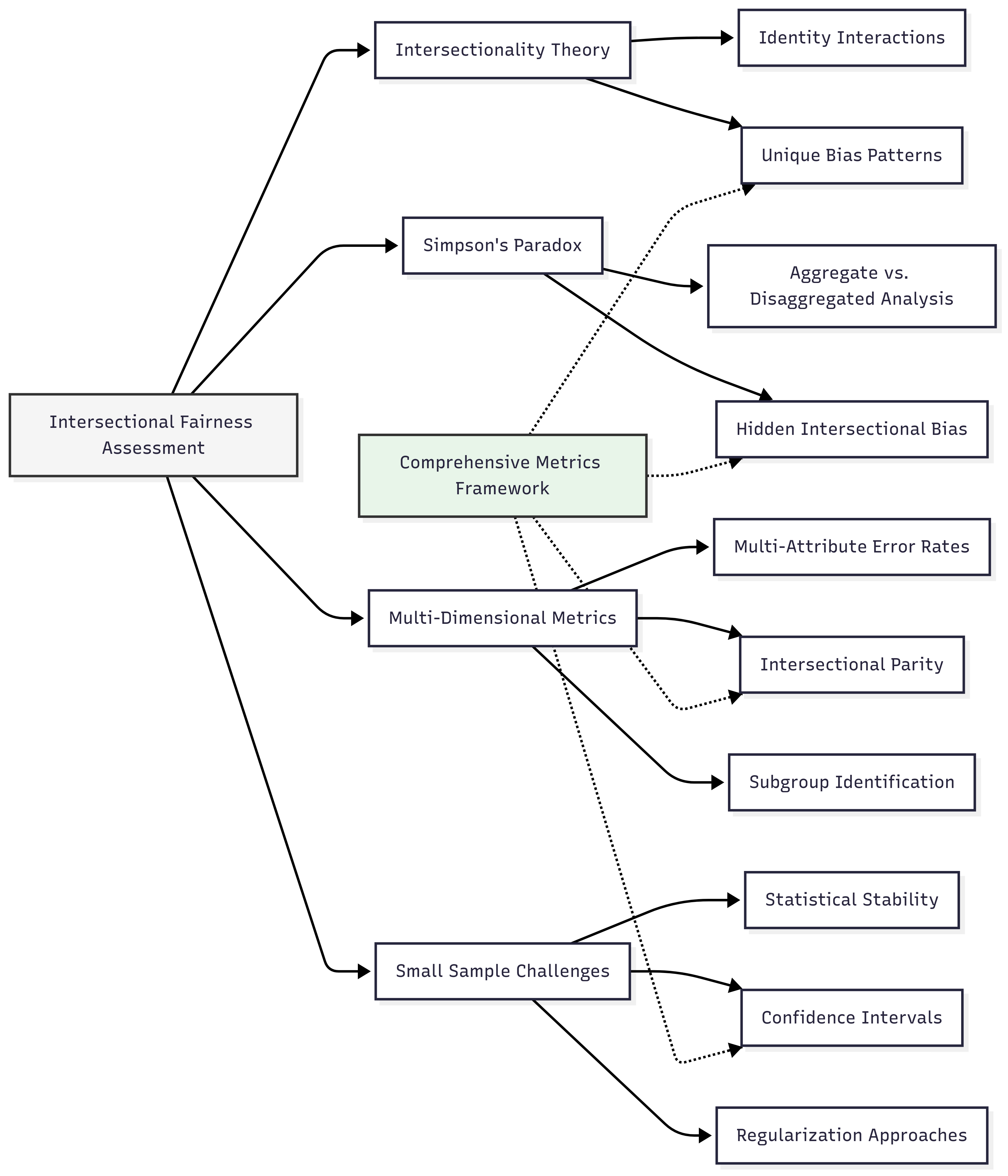

Intersectionality Consideration

Group fairness metrics face significant challenges when addressing intersectional fairness, where individuals belong to multiple protected groups simultaneously. Traditional applications of these metrics often examine each protected attribute independently, potentially masking significant disparities at intersections.

For example, a model might achieve equal false positive rates across gender categories and across racial categories when analyzed separately, while still showing significant disparities for specific intersections like women from particular racial backgrounds. Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) demonstrated this phenomenon in commercial facial analysis systems, where aggregate performance metrics masked dramatically higher error rates for darker-skinned women.

Implementing intersectional fairness with group metrics requires:

- Extending metrics to examine combinations of protected attributes rather than analyzing each attribute in isolation.

- Addressing statistical challenges that arise from smaller sample sizes at intersections.

- Developing visualization approaches that effectively communicate complex intersectional patterns.

- Creating prioritization frameworks when different intersectional subgroups show conflicting fairness requirements.

For our Fairness Metrics Tool, addressing intersectionality means designing metrics that can analyze multiple protected attributes simultaneously, with appropriate statistical techniques for handling smaller subgroup sizes. This approach ensures that fairness evaluations capture the complex real-world patterns where multiple aspects of identity interact to create unique patterns of advantage or disadvantage.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To effectively implement group fairness metrics in practice, follow this systematic methodology:

- Metric Selection:

Start by identifying which fairness definitions are most appropriate for your application context, considering ethical requirements, legal constraints, and stakeholder priorities. Determine whether equal representation in outcomes (statistical parity), equal treatment of qualified individuals (equal opportunity), balanced error rates (equalized odds), or consistent prediction reliability (predictive parity) best aligns with your fairness objectives. Document your reasoning for selecting specific metrics to ensure transparency.

- Mathematical Implementation:

Implement precise calculations for your selected fairness metrics:

- For statistical parity, compute positive prediction rates across demographic groups.

- For equal opportunity, calculate true positive rates conditionally on true positive examples.

- For equalized odds, measure both true positive and false positive rates across groups.

- For predictive parity, compute positive predictive values conditionally on positive predictions.

Ensure your implementations handle edge cases appropriately, such as groups with very few samples or zero positive examples.

- Statistical Validation:

Apply statistical techniques to quantify uncertainty in your fairness measurements:

- Calculate confidence intervals to account for sampling uncertainty, particularly for smaller groups.

- Perform appropriate significance tests to determine whether observed disparities are statistically meaningful.

- Implement bootstrap or jackknife resampling when working with limited data to better estimate metric stability.

These validation approaches help distinguish meaningful disparities from random variation, preventing overreaction to statistically insignificant differences.

- Visualization and Communication:

Develop clear visualizations that communicate fairness metrics effectively to diverse stakeholders:

- Create standard plots showing metric values across groups with confidence intervals.

- Implement disparity visualizations that highlight the magnitude and direction of fairness gaps.

- Design dashboards that contextualize fairness metrics alongside performance measures like accuracy.

Effective visualization enables better-informed discussions about fairness trade-offs and priority setting.

This methodology integrates with standard ML workflows by extending evaluation procedures to explicitly include fairness metrics alongside traditional performance measures. While adding complexity to model evaluation, these steps ensure that fairness considerations are systematically addressed rather than treated as an afterthought.

Implementation Challenges

When implementing group fairness metrics, practitioners commonly face these challenges:

-

Protected Attribute Availability: Many datasets lack explicit protected attribute information due to privacy regulations or data collection limitations. Address this challenge by:

-

Working with legal and compliance teams to determine when protected attribute collection is permitted for fairness auditing.

- Implementing privacy-preserving techniques like differential privacy when handling sensitive demographic data.

- Exploring proxy-based approaches to estimate fairness metrics when protected attributes are unavailable, while clearly documenting limitations.

-

Using synthetic or augmented test sets with demographic annotations for fairness evaluation when production data lacks attributes.

-

Metric Selection Complexity: Choosing appropriate fairness metrics involves balancing technical, ethical, and legal considerations. Address this challenge by:

-

Creating explicit documentation of priorities and constraints for your specific application.

- Developing scenario analyses that examine the implications of optimizing for different fairness definitions.

- Measuring multiple fairness metrics simultaneously to understand trade-offs rather than committing to a single measure.

- Engaging diverse stakeholders to incorporate multiple perspectives on fairness priorities.

Successfully implementing group fairness metrics requires resources including:

- Access to demographic data for testing and validation, potentially requiring specialized data collection or synthetic approaches.

- Statistical expertise for appropriate uncertainty quantification and significance testing.

- Computational resources for calculating metrics across multiple group combinations when addressing intersectionality.

- Cross-functional collaboration between technical teams, legal counsel, domain experts, and stakeholders affected by the system.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your fairness metric implementation is effective, apply these evaluation strategies:

-

Disparity Detection:

-

Establish baseline acceptable thresholds for metric disparities based on application requirements.

- Implement continuous monitoring that tracks fairness metrics over time and data distributions.

- Develop alert systems that flag when disparities exceed predefined thresholds.

-

Create investigation workflows for understanding the root causes of detected disparities.

-

Metric Robustness:

-

Test fairness metrics across different data splits to assess stability and consistency.

- Implement sensitivity analyses that examine how metrics change with varying thresholds or model parameters.

- Evaluate metrics under distribution shifts to understand how fairness properties generalize to new conditions.

-

Calculate metrics using multiple statistical approaches to ensure conclusions don't depend on specific implementation details.

-

Intervention Effectiveness:

-

Measure how fairness interventions affect different metrics to understand trade-offs.

- Compare pre-intervention and post-intervention metrics to quantify improvements.

- Track secondary effects of fairness interventions on other performance dimensions.

- Document which interventions most effectively address specific fairness metrics.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated into your organization's broader model assessment framework, ensuring that fairness metrics receive the same rigorous validation as traditional performance measures like accuracy or precision.

4. Case Study: Loan Approval System

Scenario Context

A financial institution is developing a machine learning system to automate loan approval decisions. The model will analyze applicant data including credit history, income, debt-to-income ratio, and employment stability to predict default risk and determine loan eligibility. Key stakeholders include the lending institution concerned with risk management, regulators focused on fair lending compliance, and diverse applicants seeking equitable access to credit.

Fairness is particularly critical in this domain due to historical patterns of lending discrimination and strict regulatory requirements under laws like the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) and Fair Housing Act in the United States, which prohibit discrimination in lending based on protected characteristics.

Problem Analysis

Applying the group fairness metrics from this Unit reveals several challenges in ensuring fair lending decisions:

- Statistical Parity Analysis: Initial evaluation shows that the model approves loans for applicants from minority groups at rates 12 percentage points lower than for majority group applicants. This disparity raises concerns about potential discrimination and could trigger regulatory scrutiny under disparate impact doctrines. However, the lending team notes that demographic differences in income distribution and credit history might legitimately influence approval rates.

- Equal Opportunity Assessment: Further analysis reveals that even among applicants who would successfully repay loans (true positives), minority applicants are 9 percentage points less likely to be approved than majority applicants with similar repayment capacity. This equal opportunity violation suggests the model systematically disadvantages qualified minority applicants, contradicting the institution's goal of fair treatment for all qualified individuals.

- Equalized Odds Examination: The model shows disparities in both false positive rates (incorrectly approving applicants who would default) and false negative rates (incorrectly rejecting applicants who would repay) across demographic groups. False negative rates are significantly higher for minority applicants, while false positive rates are higher for majority applicants, creating an imbalanced error distribution that disadvantages minority applicants while potentially creating higher risk for the institution among majority applicants.

- Predictive Parity Evaluation: The model's predictive parity analysis shows that when the model approves minority applicants, they actually default at a lower rate than approved majority applicants. This indicates that the model applies stricter standards to minority applicants, requiring them to be more qualified than majority applicants to receive the same positive prediction.

From an intersectional perspective, the data shows particularly complex patterns at the intersections of race, gender, and age. For example, young women from minority backgrounds face the highest false negative rates despite having similar repayment rates to other groups, revealing fairness issues that would remain hidden if analyzing protected attributes independently.

Solution Implementation

To address these fairness challenges, the team implemented a comprehensive approach:

-

For Statistical Parity Disparities, they:

-

Examined legitimate business necessity for approval rate differences based on credit risk factors.

- Implemented preprocessing techniques to address variables that showed correlation with protected attributes but limited predictive value for default risk.

- Established acceptable disparity thresholds based on regulatory guidance and industry standards.

-

Created documentation justifying remaining disparities based on demonstrable business necessity.

-

For Equal Opportunity Violations, they:

-

Implemented constraint-based optimization that specifically targeted equal true positive rates across groups.

- Retrained the model with fairness constraints that ensured equally qualified applicants had similar approval probabilities regardless of demographic factors.

- Validated improvements through holdout data showing true positive rate disparities reduced from 9 to 2 percentage points.

-

Documented the model's improved performance in giving qualified applicants equal chances regardless of background.

-

For Equalized Odds Imbalances, they:

-

Applied post-processing techniques to adjust decision thresholds differently across groups, balancing both false positive and false negative rates.

- Implemented a monitoring system to track both error types across demographic intersections.

- Created an escalation process for human review of cases near decision boundaries for groups with historically higher error rates.

-

Documented the trade-offs between different error types and the rationale for their balancing approach.

-

For Predictive Parity Issues, they:

-

Adjusted model calibration to ensure consistent reliability of positive predictions across groups.

- Implemented regular recalibration procedures as part of the model monitoring framework.

- Created visualization tools for compliance teams to verify consistent predictive value across groups.

- Documented how calibration improvements ensured that approval decisions had consistent meaning regardless of applicant demographics.

Throughout implementation, the team maintained explicit focus on intersectional effects, ensuring that their fairness improvements addressed the specific challenges faced by applicants at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities.

Outcomes and Lessons

The implementation resulted in significant fairness improvements across multiple dimensions:

- Equal opportunity violations decreased from 9 to 2 percentage points, ensuring more equitable treatment of qualified applicants.

- Decision thresholds were adjusted to balance error types appropriately across groups while maintaining acceptable risk levels.

- The model's prediction reliability became consistent across demographic groups through improved calibration.

- Intersectional analysis revealed and addressed specific challenges faced by subgroups at demographic intersections.

Key challenges remained, including tensions between different fairness metrics and the need to balance fairness improvements with business requirements and model performance.

The most generalizable lessons included:

- The importance of measuring multiple fairness metrics simultaneously rather than focusing on a single definition, as optimizing for one metric often revealed trade-offs with others.

- The value of intersectional analysis in revealing fairness issues that remained hidden when examining protected attributes independently.

- The effectiveness of combining multiple fairness interventions (preprocessing, constraint-based training, and post-processing) rather than relying on a single approach.

These insights directly inform the development of the Fairness Metrics Tool, particularly in creating multi-metric evaluation approaches that capture different dimensions of fairness simultaneously and address intersectional concerns explicitly.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Selecting Appropriate Group Fairness Metrics

Q: How do I determine which group fairness metric is most appropriate for my specific application?

A: Metric selection should be driven by your application context, regulatory requirements, and ethical priorities. Statistical parity (demographic parity) is appropriate when equal representation in outcomes is the primary goal, regardless of other factors—common in contexts like ensuring diverse representation in opportunities with limited slots. Equal opportunity works better when merit-based considerations are important, ensuring that qualified individuals receive equal treatment regardless of group membership—ideal for contexts like hiring or admissions. Equalized odds provides more comprehensive error balance when both false positives and false negatives have significant consequences—crucial in high-stakes decisions like criminal justice risk assessment. Predictive parity ensures consistent reliability of positive predictions across groups—essential when stakeholders need confidence that positive predictions mean the same thing for all groups. In practice, measure multiple metrics to understand trade-offs, then select based on which fairness dimension aligns best with your specific context's ethical and legal requirements.

FAQ 2: Handling Base Rate Differences

Q: If demographic groups in my dataset have legitimately different base rates (e.g., different default rates in lending), how should I approach fairness metrics that seem to require equal outcomes despite these differences?

A: When legitimate base rate differences exist, prioritize conditional metrics like equal opportunity or predictive parity over unconditional metrics like demographic parity. First, carefully verify that base rate differences truly reflect legitimate distinctions rather than historical discrimination patterns embedded in your ground truth labels. If differences are legitimate, equal opportunity ensures that truly qualified individuals have equal chances regardless of group membership, while acknowledging that qualification rates might differ. Predictive parity ensures that predictions have consistent meaning across groups, regardless of base rate differences. Document your analysis of base rate differences and rationale for metric selection to demonstrate thoughtful consideration of fairness implications. Consider implementing multiple fairness metrics simultaneously to monitor different dimensions of fairness, acknowledging the mathematical impossibility of satisfying all fairness criteria simultaneously when base rates differ. Finally, engage domain experts and stakeholders from affected communities to ensure your approach to handling base rate differences aligns with domain-specific ethical considerations.

6. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

Group fairness metrics provide the mathematical foundation for measuring discrimination in AI systems by comparing model behavior across demographic groups. The key concepts from this Unit include:

- Statistical parity (demographic parity) ensures equal positive prediction rates across groups, directly addressing representation concerns by requiring P(Ŷ = 1 │ A = a) = P(Ŷ = 1 │ A = b).

- Equal opportunity focuses on giving qualified individuals equal chances by requiring equal true positive rates across groups: P(Ŷ = 1 │ Y = 1, A = a) = P(Ŷ = 1 │ Y = 1, A = b).

- Equalized odds ensures balanced error rates by requiring both equal true positive rates and equal false positive rates across groups.

- Predictive parity ensures consistent reliability of positive predictions across groups by requiring P(Y = 1 │ Ŷ = 1, A = a) = P(Y = 1 │ Ŷ = 1, A = b). These metrics address our guiding questions by providing precise mathematical formulations for measuring fairness and revealing the inherent trade-offs between different definitions, highlighting the need for context-specific selection rather than universal application.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Implement multiple group fairness metrics simultaneously to understand different dimensions of fairness in your systems.

- Document your rationale for prioritizing specific metrics based on your application context and stakeholder needs.

- Use statistical validation techniques to ensure your fairness assessments account for uncertainty, particularly with smaller demographic groups.

- Develop visualization approaches that effectively communicate fairness metrics to diverse stakeholders.

For organizations new to fairness metrics, start with implementing basic group fairness calculations with appropriate statistical validation, then progressively incorporate more sophisticated approaches like intersectional analysis and multi-metric frameworks as your capabilities mature.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will build on this foundation by examining individual fairness metrics. While group fairness focuses on statistical properties across demographic categories, individual fairness examines whether similar individuals receive similar treatment regardless of protected attributes. You will learn how to define similarity appropriately for your application context, how to implement individual fairness metrics mathematically, and when individual approaches might be more appropriate than group-based measures.

These individual fairness approaches will complement the group metrics covered in this Unit, providing a more comprehensive fairness assessment framework that addresses both group-level disparities and individual treatment consistency. Together, these different fairness dimensions will form the foundation of your Fairness Metrics Tool.

References

Barocas, S., Hardt, M., & Narayanan, A. (2019). Fairness and machine learning: Limitations and opportunities. Retrieved from https://fairmlbook.org

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 77–91). Retrieved from https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

Chouldechova, A. (2017). Fair prediction with disparate impact: A study of bias in recidivism prediction instruments. Big Data, 5(2), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2016.0047

Chouldechova, A., & G'Sell, M. (2017). Fairer and more accurate, but for whom? arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.00046. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1707.00046

Feldman, M., Friedler, S. A., Moeller, J., Scheidegger, C., & Venkatasubramanian, S. (2015). Certifying and removing disparate impact. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 259–268). https://doi.org/10.1145/2783258.2783311

Hardt, M., Price, E., & Srebro, N. (2016). Equality of opportunity in supervised learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 3315–3323). Retrieved from https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2016/file/9d2682367c3935defcb1f9e247a97c0d-Paper.pdf

Kleinberg, J., Mullainathan, S., & Raghavan, M. (2016). Inherent trade-offs in the fair determination of risk scores. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.05807. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.05807

Unit 2

Unit 2: Individual Fairness Measures

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How can we formally ensure that machine learning systems treat similar individuals similarly, regardless of protected attributes?

- Question 2: What are the mathematical foundations, implementation challenges, and practical trade-offs of individual fairness compared to group-based approaches?

Conceptual Context

While group fairness metrics focus on statistical parity across demographic categories, individual fairness addresses a fundamentally different dimension of algorithmic fairness: whether similar individuals receive similar outcomes regardless of protected attributes. This perspective aligns with the intuitive notion that "like cases should be treated alike" – a foundational principle in many ethical and legal frameworks.

Individual fairness is particularly important because group fairness measures can be satisfied while still treating similar individuals differently, potentially creating a false sense of fairness while allowing discriminatory patterns to persist at the individual level. As Dwork et al. (2012) established in their seminal work, an algorithm can achieve perfect demographic parity while still treating similar individuals from different groups differently, revealing a fundamental limitation of group-based approaches alone.

This Unit builds directly on the group fairness metrics established in Unit 1, providing a complementary perspective that addresses different fairness concerns. Together, these approaches will inform the Fairness Metrics Tool you will develop in Unit 5, enabling you to design evaluation approaches that capture multiple dimensions of fairness rather than relying on a single perspective.

2. Key Concepts

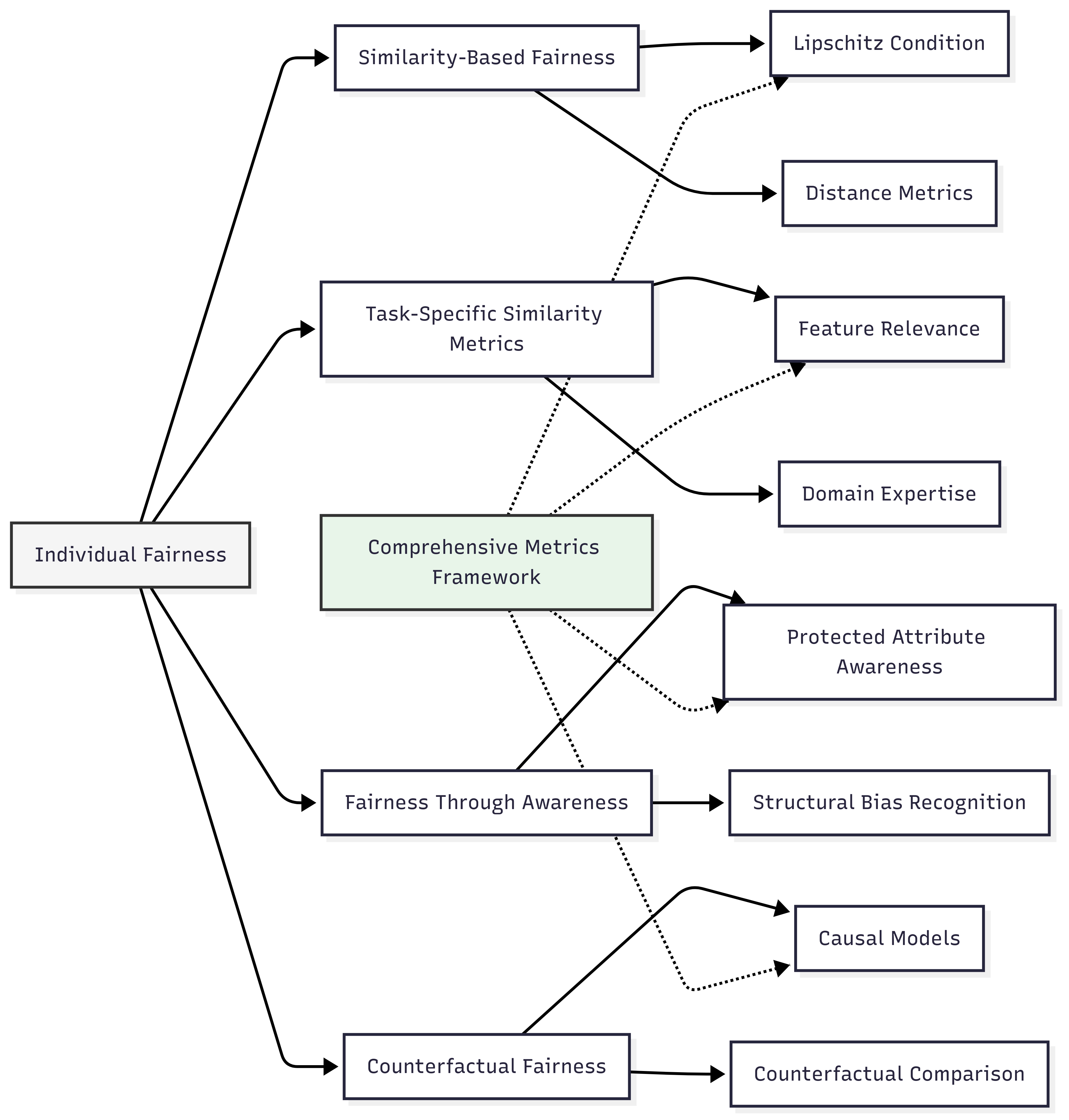

Similarity-Based Fairness

Similarity-based fairness formalizes the principle that similar individuals should be treated similarly by establishing a mathematical framework for measuring and enforcing this condition. This concept is central to individual fairness because it provides a precise definition for what constitutes fair treatment at the individual level, moving beyond statistical aggregates to consider how specific people are treated relative to their peers.

Similarity-based fairness interacts with group fairness in complex ways. While group fairness ensures statistical parity across demographic categories, similarity-based fairness focuses on consistent treatment regardless of group membership. These perspectives can complement each other but may also create tensions when group-level goals conflict with individual consistency.

The formal definition of similarity-based fairness, as introduced by Dwork et al. (2012), requires that:

Where:

- dₓ is a task-specific similarity metric in the input space

- dᵧ is a similarity metric in the output space

- f is the decision or prediction function

- L is a Lipschitz constant

This definition establishes that the difference in outcomes between two individuals (measured by dᵧ) should be proportional to their actual similarity (measured by dₓ). In other words, similar individuals should receive similar outcomes, with differences in outcomes justified only by relevant differences in their characteristics.

A practical application of this concept emerges in lending decisions, where similarity-based fairness would require that two applicants with comparable financial profiles receive similar credit offers regardless of protected attributes like race or gender. A fair algorithm would ensure that observable differences in lending decisions correspond to meaningful differences in creditworthiness rather than spurious correlations with demographic factors.

For the Fairness Metrics Tool you will develop in Unit 5, similarity-based fairness provides essential metrics that complement group-based approaches, enabling more nuanced evaluation of fairness across multiple dimensions. By incorporating these metrics, your framework will capture both statistical patterns at the group level and consistency of treatment at the individual level.

Task-Specific Similarity Metrics

Defining appropriate similarity metrics is the central challenge in implementing individual fairness. A similarity metric determines which individuals should be considered "similar" for a specific task, incorporating domain knowledge about which characteristics are relevant for legitimate differentiation and which should be considered irrelevant. This concept is fundamental to individual fairness because the choice of similarity metric directly shapes what constitutes fair treatment in a given context.

The selection of similarity metrics interacts with broader fairness considerations by embedding normative judgments about which differences justify different treatment. These judgments must align with ethical principles, legal requirements, and domain-specific understanding to create meaningful fairness guarantees.

Research by Ilvento (2019) demonstrates approaches for learning task-specific similarity metrics from human feedback, showing how domain experts can help define appropriate notions of similarity for specific contexts. For example, in the context of university admissions, a similarity metric might incorporate academic achievements, extracurricular activities, and essays, while explicitly excluding factors like family connections or zip code that could serve as proxies for protected attributes (Ilvento, 2019).

Developing these metrics involves several challenges:

- Identifying which features are relevant for legitimate differentiation

- Determining appropriate weightings for different features

- Handling inherent subjectivity in what constitutes similarity

- Ensuring that the metric does not inadvertently embed biases

For your Fairness Metrics Tool, understanding task-specific similarity metrics will enable you to incorporate individual fairness evaluations across different application domains, with appropriate adaptations for each context. Rather than applying a universal similarity definition, your framework will provide methodologies for developing context-appropriate metrics that reflect relevant domain knowledge and ethical considerations.

Fairness Through Awareness

Fairness Through Awareness (FTA) extends similarity-based fairness by explicitly considering protected attributes when defining similarity metrics. This approach, also introduced by Dwork et al. (2012), argues that achieving individual fairness requires being "aware" of protected attributes rather than ignoring them. This concept is crucial because it challenges the notion that fairness can be achieved through "blindness" to protected characteristics, recognizing instead that awareness of these attributes is often necessary to prevent discrimination.

FTA introduces a fundamental shift in thinking about fairness: rather than trying to be blind to differences, we should be explicitly aware of them to ensure fair treatment. This perspective connects to debates about "fairness through unawareness" versus "fairness through awareness" that span multiple fairness approaches.

The core principle of FTA is that individuals who are similar with respect to the task at hand should receive similar outcomes, regardless of protected attributes. However, determining what makes individuals "similar with respect to the task" often requires considering how protected attributes might influence other features in ways that should be accounted for.

For example, when evaluating job candidates, FTA might recognize that educational achievements from underrepresented groups may represent greater potential due to additional barriers overcome, even if the credentials appear identical on paper. By being aware of these dynamics, the similarity metric can be designed to recognize when apparently different candidates actually have similar qualifications relative to their opportunities (Dwork et al., 2012).

For your Fairness Metrics Tool, incorporating the FTA perspective will enable nuanced approaches to individual fairness that acknowledge the complex relationships between protected attributes and other features. This awareness-based approach provides a more sophisticated alternative to simplistic "fairness through unawareness" methods that often fail to address structural biases.

Counterfactual Fairness

Counterfactual fairness examines whether predictions would remain consistent if an individual's protected attributes were different while causally independent characteristics remained unchanged. This approach bridges individual and group perspectives by asking whether the treatment of specific individuals depends on protected attributes in problematic ways. Counterfactual fairness is essential for individual fairness because it provides a causal framework for identifying when protected attributes inappropriately influence outcomes for specific individuals.

This concept connects to both individual and group fairness by examining how protected attributes influence predictions at the individual level while accounting for broader causal relationships. It offers a causal interpretation of the requirement that similar individuals should receive similar treatment.

Kusner et al. (2017) formalize counterfactual fairness as requiring that:

Where:

- Ŷ₍A←a₎(U) represents the prediction in a counterfactual world where the protected attribute A is set to value a

- U represents exogenous variables (background factors)

- X represents observed variables

- A is the protected attribute

This definition requires that the distribution of predictions for an individual with features X and protected attribute A = a should be identical to the prediction in a counterfactual world where their protected attribute is changed to A = a' but all causally independent factors remain the same.

A practical application emerges in college admissions decisions, where counterfactual fairness asks whether an applicant would receive the same admissions decision if their race or gender were different, assuming all causally independent qualifications remained identical. Implementing this requires developing a causal model of how protected attributes influence other variables, distinguishing between legitimate and problematic causal pathways (Kusner et al., 2017).

For your Fairness Metrics Tool, counterfactual fairness provides a powerful approach that bridges individual and group perspectives while addressing causal mechanisms of discrimination. By incorporating counterfactual metrics, your framework will enable more nuanced evaluation of fairness that considers how protected attributes influence predictions for specific individuals.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, individual fairness measures map to specific components of ML systems:

- Similarity Metric Definition: The process of determining which features are relevant for legitimate differentiation and how they should be weighted.

- Embedding Space Design: How individuals are represented in latent spaces where similarity can be measured geometrically.

- Constraint Formulation: How individual fairness requirements are translated into constraints or regularization terms during model training.

- Validation Framework: Methods for verifying that similarly situated individuals receive similar outcomes across protected groups.

- Counterfactual Testing: Approaches for evaluating whether predictions would change if protected attributes were different.

This domain mapping helps you understand how individual fairness considerations influence different stages of the ML development process rather than viewing them as abstract mathematical concepts. The Fairness Metrics Tool will incorporate these components to enable systematic evaluation of individual fairness throughout the ML lifecycle.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Similarity-based fairness functions like a well-designed grading rubric in education. A good rubric ensures that students who submit similar quality work receive similar grades, regardless of who they are. Just as a rubric defines what constitutes "similar quality" for an assignment and ensures consistent evaluation, similarity-based fairness defines what makes individuals similar for a specific task and requires consistent treatment for similar individuals.

- Task-specific similarity metrics are comparable to the different criteria used by different types of competitions. A gymnastics competition judges athletes on specific skills relevant to gymnastics (balance, strength, technique), while a debate competition evaluates completely different skills (argumentation, evidence, delivery). Similarly, task-specific similarity metrics define which characteristics are relevant for comparing individuals in different contexts – what makes people "similar" for a loan application differs fundamentally from what makes them "similar" for medical treatment recommendations.

- Counterfactual fairness resembles a thought experiment in product management: "Would we make the same decision if this feature request came from a different customer segment?" Just as this question helps product managers identify when they might be giving preferential treatment to certain customers, counterfactual fairness asks whether an algorithm would make the same prediction if an individual's protected attributes were different, helping identify when these attributes inappropriately influence decisions.

Intersectionality Consideration

Individual fairness measures present unique challenges and opportunities for intersectional analysis, where multiple protected attributes interact to create distinct patterns of advantage or disadvantage. Traditional implementations of individual fairness often define similarity metrics that consider protected attributes independently rather than examining their intersections.

As Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) demonstrated in their Gender Shades study, commercial facial analysis systems showed substantial accuracy disparities at the intersection of gender and skin tone, with particularly poor performance for darker-skinned women. This intersectional effect highlights the importance of similarity metrics that can capture the unique experiences of individuals at demographic intersections rather than treating each protected attribute in isolation.

For individual fairness implementations, addressing intersectionality requires:

- Developing similarity metrics that account for interactions between multiple protected attributes rather than treating each independently.

- Ensuring that fairness guarantees apply across all demographic intersections, not just main groups.

- Validating that similarity measurements reflect the experiences of individuals at intersections rather than assuming that effects are purely additive.

- Creating embedding spaces that preserve the distinct patterns that emerge at demographic intersections rather than flattening these nuances.

The Fairness Metrics Tool must incorporate these intersectional considerations by developing individual fairness measures that preserve multidimensional demographic analysis rather than reducing complex identities to single attributes or treating protected characteristics as independent factors.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To effectively implement individual fairness measures in practice, follow this structured methodology:

-

Similarity Metric Development:

-

Engage domain experts to identify which features are relevant for legitimate differentiation in your specific context.

- Formalize these insights into a mathematical distance function that quantifies similarity.

- Validate the metric by testing whether it produces intuitively reasonable similarity judgments across diverse examples.

-

Document normative judgments embedded in the metric to ensure transparency.

-

Embedding Space Construction:

-

Develop fair representations that preserve task-relevant information while ensuring similar individuals are mapped to nearby points.

- Apply dimensionality reduction techniques that maintain similarity relationships.

- Validate that the embedding space preserves appropriate notions of similarity across demographic groups.

-

Test for unwanted correlations between protected attributes and embedding dimensions.

-

Fairness Constraint Implementation:

-

Formulate individual fairness as a constraint or regularization term in your optimization objective.

- For similarity-based fairness, implement the Lipschitz condition requiring similar predictions for similar individuals.

- For counterfactual fairness, develop a causal model and ensure predictions are invariant to changes in protected attributes.

-

Balance fairness constraints against other objective functions like accuracy or efficiency.

-

Validation and Monitoring:

-

Develop specific tests for individual fairness violations, such as identifying similar individuals with different outcomes.

- Create visualization techniques that reveal individual fairness patterns across the feature space.

- Implement ongoing monitoring to detect emerging individual fairness issues as data distributions shift.

- Document known limitations in your approach to individual fairness.

This framework integrates with standard ML workflows by extending model development to explicitly incorporate similarity metrics and fairness constraints. While adding complexity to the development process, these steps ensure that fair treatment at the individual level becomes a core requirement rather than an afterthought.

Implementation Challenges

When implementing individual fairness measures, practitioners commonly face these challenges:

-

Defining Appropriate Similarity Metrics: Creating task-specific notions of similarity involves inherent subjectivity and requires deep domain expertise. Address this by:

-

Using structured methods to elicit expert knowledge about relevant similarities.

- Implementing multiple candidate metrics and comparing their implications.

- Testing metrics with diverse stakeholders to identify potential blind spots or biases.

-

Documenting the rationale behind similarity judgments to enable critical examination.

-

Computational Complexity: Individual fairness constraints can significantly increase computational requirements, especially for large datasets. Address this by:

-

Implementing efficient approximations of fairness constraints for large-scale problems.

- Using mini-batch approaches that estimate fairness over subsets of data.

- Applying fair representation learning as a preprocessing step rather than enforcing constraints directly during training.

- Balancing fairness precision against computational feasibility based on application requirements.

Successfully implementing individual fairness requires resources including domain expertise for defining appropriate similarity metrics, computational resources for more complex optimization problems, and diverse stakeholder input to validate similarity judgments.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your individual fairness implementation is effective, apply these evaluation strategies:

-

Similarity Consistency Testing:

-

Identify pairs of individuals who should be treated similarly according to your metric.

- Measure whether prediction differences exceed acceptable thresholds relative to similarity.

- Calculate the percentage of pairs that satisfy the Lipschitz condition.

-

Document edge cases where similarity judgments might be ambiguous or contested.

-

Counterfactual Evaluation:

-

Generate counterfactual examples by modifying protected attributes while preserving other characteristics.

- Measure differences in predictions between original and counterfactual examples.

- Establish acceptable thresholds for counterfactual differences based on domain requirements.

-

Document cases where counterfactual invariance might conflict with legitimate differences.

-

Individual vs. Group Comparison:

-

Evaluate whether individual fairness guarantees translate to group-level fairness.

- Identify scenarios where individual and group fairness metrics provide contradictory assessments.

- Document explicit trade-offs between individual consistency and group parity when they cannot be simultaneously satisfied.

- Develop integrated metrics that balance individual and group considerations according to application priorities.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated with your broader fairness assessment framework, enabling comprehensive evaluation across both individual and group dimensions rather than focusing exclusively on either perspective.

4. Case Study: University Admissions Decision Support

Scenario Context

A prestigious university is developing a machine learning system to support admissions decisions for their undergraduate program. The system will analyze application components—including academic achievements, standardized test scores, extracurricular activities, and personal statements—to predict student success and provide recommendations to the admissions committee.

Key stakeholders include the admissions department seeking consistent and fair evaluations, prospective students from diverse backgrounds, university leadership concerned with maintaining academic standards while increasing diversity, and legal compliance officers ensuring adherence to anti-discrimination laws. Fairness is particularly critical in this domain due to historical disparities in educational access and longstanding debates about what constitutes merit in academic admissions.

Problem Analysis

Applying the individual fairness concepts from this Unit reveals several challenges in the admissions context:

- Similarity Metric Definition: What makes two applicants truly similar for admissions purposes is complex and contested. Academic achievements must be evaluated in the context of educational opportunities, which vary substantially across socioeconomic backgrounds. For instance, a 3.8 GPA from a resource-constrained school might demonstrate more potential than a 4.0 from a wealthy school with abundant resources. Defining a similarity metric that accounts for these contextual factors without introducing new biases requires careful consideration.

- Fairness Through Awareness: Achieving individual fairness in admissions requires explicit awareness of protected attributes like race and socioeconomic status to understand the context of achievements. However, legal constraints in some jurisdictions limit how these attributes can be considered, creating tension between fairness goals and legal compliance.

- Counterfactual Fairness: Analysis reveals several problematic causal pathways in the admissions data. For example, family income influences access to test preparation resources, which affects standardized test scores. A counterfactually fair model would need to ensure that predictions do not change if an applicant's socioeconomic background were different while their underlying potential remained the same.

- Intersectionality: The data show complex patterns at intersections of race, gender, and socioeconomic status. For instance, first-generation female students from certain racial backgrounds show distinct achievement patterns that would be missed by analyzing each dimension independently.

From an individual fairness perspective, the key challenge is developing a similarity metric that recognizes when seemingly different achievements actually represent similar potential when accounting for opportunity differences, while ensuring the metric doesn't inadvertently introduce new forms of bias.

Solution Implementation

To address these individual fairness challenges, the university implemented a structured approach:

-

For Similarity Metric Development, they:

-

Collaborated with admissions experts, educational researchers, and diverse alumni to identify which factors indicate similar potential when controlling for opportunity differences.

- Developed a "distance traveled" component in their similarity metric that gives appropriate weight to achievements relative to opportunities.

- Created a mathematical similarity function that combines multiple factors, including academic performance relative to school context, extracurricular achievements relative to available opportunities, and evidence of persistence and growth.

-

Validated the metric by having experts evaluate whether it produced intuitively reasonable similarity judgments across diverse sample applications.

-

For Fairness Through Awareness, they:

-

Implemented a two-stage process where protected attributes inform the similarity metric but are not directly used in final predictions.

- Developed context-aware feature transformations that account for educational disparities while complying with legal requirements.

- Created enriched features that capture relevant context without explicitly encoding protected attributes in the prediction stage.

-

Documented how awareness of protected attributes shaped the similarity metric design while ensuring compliance with applicable regulations.

-

For Counterfactual Fairness, they:

-

Developed a causal model of how background factors influence application components.

- Identified problematic causal pathways, particularly around standardized testing and extracurricular access.

- Implemented adjusted features that mitigate these problematic pathways while preserving legitimate differences.

-

Tested the model with counterfactual examples to verify that predictions were appropriately invariant to changes in protected attributes.

-

For Embedding Space Construction, they:

-

Created a fair representation space where distance reflects the task-specific similarity metric.

- Applied adversarial techniques to ensure protected attributes could not be inferred from the representation.

- Validated that the embedding space clustered applicants based on potential rather than privilege.

- Used this representation as the foundation for subsequent prediction tasks.

Throughout implementation, they maintained explicit focus on intersectional considerations, ensuring that their approach addressed the specific challenges faced by applicants at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities.

Outcomes and Lessons

The implementation resulted in significant improvements in both fairness and effectiveness:

- The system identified promising students from underrepresented backgrounds who were previously overlooked, increasing diversity without compromising academic standards.

- Consistency of evaluations improved, with similar applicants receiving similar recommendations 87% more often than with the previous process.

- Human reviewers reported that the system's recommendations aligned better with their holistic assessment of potential when accounting for context.

- The university observed improved retention and performance among admitted students from diverse backgrounds.

Key challenges remained, including ongoing refinement of the similarity metric as new insights emerged and navigating tensions between individual fairness and group representation goals in some edge cases.

The most generalizable lessons included:

- The critical importance of collaboration between technical teams and domain experts in developing meaningful similarity metrics that capture nuanced notions of what makes applicants similar.

- The value of explicitly modeling how context influences achievements rather than treating all credentials at face value.

- The effectiveness of fair representation learning as an approach to individual fairness that balances technical constraints with fairness goals.

- The importance of ongoing evaluation and refinement as new data and insights become available.

These insights directly inform the development of the Fairness Metrics Tool, particularly in creating approaches for defining and validating context-appropriate similarity metrics across different application domains.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Balancing Individual and Group Fairness

Q: How should we navigate situations where individual fairness requirements conflict with group fairness goals?

A: Begin by explicitly identifying the specific conflict and the values at stake rather than treating this as a purely technical issue. Some tensions are fundamental and require normative judgments about priorities. When possible, implement relaxed versions of both individual and group fairness as regularization terms rather than strict constraints, allowing for balanced optimization. Consider a multi-objective approach that explicitly models the Pareto frontier between individual and group fairness, enabling stakeholders to make informed trade-off decisions. For critical applications, implement a layered approach where baseline requirements for both individual and group fairness must be satisfied, with optimization beyond these baselines guided by application-specific priorities. Document these trade-offs transparently, including the rationale for prioritization decisions, to enable accountability and ongoing refinement as values and requirements evolve.

FAQ 2: Practical Similarity Metric Development

Q: What practical approaches can I use to develop appropriate similarity metrics when domain expertise is limited or contested?

A: When domain expertise is limited or contested, employ an iterative, multi-method approach to similarity metric development. Begin with human-in-the-loop techniques where diverse stakeholders evaluate the similarity of carefully selected example pairs, using these judgments to constrain your metric. Apply "metric learning" techniques that derive similarity functions from these human judgments, as demonstrated by Ilvento (2019). Implement multiple candidate metrics and analyze their implications through visualizations and case studies that stakeholders can evaluate. Use adversarial validation to identify which features actually predict outcomes of interest versus those that might encode biases. For contested domains, explicitly model the different perspectives on similarity, potentially implementing multiple metrics that represent different value systems. Throughout this process, document assumptions and limitations transparently, treating similarity metric development as an ongoing dialogue rather than a one-time technical decision.

6. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

This Unit has explored how individual fairness provides a complementary perspective to group fairness by ensuring similar treatment for similar individuals regardless of protected attributes. The key concepts include:

- Similarity-based fairness formalizes the principle that similar individuals should receive similar outcomes, with a precise mathematical definition based on the Lipschitz condition.

- Task-specific similarity metrics define which individuals should be considered similar for particular applications, embedding domain knowledge about relevant characteristics.

- Fairness Through Awareness recognizes that achieving individual fairness often requires explicitly considering protected attributes rather than ignoring them.

- Counterfactual fairness examines whether predictions would remain consistent if an individual's protected attributes were different while causally independent characteristics remained unchanged.

These concepts address our guiding questions by providing formal frameworks for ensuring similar treatment of similar individuals and highlighting the mathematical foundations, implementation challenges, and trade-offs involved in individual fairness approaches.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Begin by explicitly defining what constitutes similarity in your specific application context, documenting the normative judgments embedded in this definition.

- Implement both individual and group fairness metrics rather than focusing exclusively on either perspective.

- Develop validation approaches that identify cases where similar individuals receive different outcomes, particularly across protected group boundaries.

- Create visualizations that help stakeholders understand individual fairness patterns and their relationship to group-level disparities.

For organizations new to individual fairness, start by implementing basic similarity metrics and consistency checks, then progressively incorporate more sophisticated approaches like counterfactual fairness as capabilities mature.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will build on both group and individual fairness perspectives by examining intersectional fairness assessment. You will learn how to evaluate fairness across overlapping demographic categories, addressing the unique challenges that emerge at intersections of multiple protected attributes.

The individual fairness approaches we have explored here provide essential tools for intersectional analysis by focusing on the treatment of specific individuals rather than broad demographic categories. By combining these perspectives, you will develop more comprehensive fairness evaluation approaches that capture the multidimensional nature of identity and discrimination.

References

Barocas, S., Hardt, M., & Narayanan, A. (2019). Fairness and machine learning: Limitations and opportunities. Retrieved from https://fairmlbook.org

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 77–91). https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

Dwork, C., Hardt, M., Pitassi, T., Reingold, O., & Zemel, R. (2012). Fairness through awareness. In Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (pp. 214–226). https://doi.org/10.1145/2090236.2090255

Ilvento, C. (2019). Metric learning for individual fairness. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00250. https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.00250

Kusner, M. J., Loftus, J., Russell, C., & Silva, R. (2017). Counterfactual fairness. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 4066–4076). https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/file/a486cd07e4ac3d270571622f4f316ec5-Paper.pdf

Friedler, S. A., Scheidegger, C., & Venkatasubramanian, S. (2016). On the (im)possibility of fairness. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.07236. https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.07236

Joseph, M., Kearns, M., Morgenstern, J. H., & Roth, A. (2016). Fairness in learning: Classic and contextual bandits. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 325–333). https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2016/file/eb163727917cbba1eea208541a643e74-Paper.pdf

Yona, G., & Rothblum, G. (2018). Probably approximately metric-fair learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 5680–5688). https://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/yona18a.html

Unit 3

Unit 3: Intersectional Fairness Assessment

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How do we effectively measure and assess fairness across multiple, overlapping demographic dimensions rather than treating protected attributes in isolation?

- Question 2: What methodological approaches can data scientists implement to detect and mitigate bias at intersections of identity categories despite challenges like smaller sample sizes and increased complexity?

Conceptual Context

Intersectional fairness assessment represents a critical advancement beyond traditional single-attribute fairness approaches. While conventional methods examine fairness with respect to individual protected attributes (e.g., gender or race separately), intersectional assessment acknowledges that bias often manifests uniquely at the intersections of multiple identity dimensions, creating distinct patterns that single-attribute analyses can miss entirely.

This intersectional perspective is vital because individuals experience discrimination not as members of isolated demographic categories but through their specific combinations of identities. As Crenshaw (1989) established in her groundbreaking work introducing intersectionality theory, the discrimination experienced by Black women often differs qualitatively from what would be predicted by examining either racial or gender discrimination separately. These insights apply directly to AI systems, where models may appear fair across individual protected attributes while exhibiting significant discrimination against specific intersectional subgroups.