Sprint 2: Technical Approaches to Fairness

Introduction

How do you translate fairness principles into concrete interventions within machine learning systems? This Sprint tackles this critical challenge. Without systematic bias mitigation approaches, fairness remains conceptual rather than operational.

This Sprint builds directly on Sprint 1's Fairness Audit Playbook. You now move from identifying bias to eliminating it. Think of Sprint 1 as diagnosis and Sprint 2 as treatment. First you located the problem; now you'll fix it. The Sprint Project adopts a domain-driven approach, working backwards from our desired outcome—a practical framework for selecting and implementing fairness interventions.

By the end of this Sprint, you will:

- Analyze causal mechanisms of bias by mapping relationships between protected attributes, features, and outcomes.

- Design pre-processing interventions by transforming, reweighting, and resampling your data.

- Implement fairness-aware modeling by incorporating constraints, adversarial techniques, and regularization.

- Apply post-processing techniques by optimizing thresholds and calibrating outputs.

- Create integrated intervention strategies by combining techniques across the ML pipeline.

Sprint Project Overview

Project Description

In this Sprint, you will develop a Fairness Intervention Playbook—a decision-making methodology for selecting, configuring, and evaluating technical fairness interventions. This playbook transforms diagnosis into treatment, connecting issues identified in your Fairness Audit Playbook to specific technical solutions.

The Fairness Intervention Playbook helps you select optimal intervention points, match techniques to specific bias patterns, and integrate multiple approaches. Rather than prescribing universal solutions, it guides you through systematic selection based on your fairness definitions, bias sources, and technical constraints. Consider it your fairness treatment plan—a customized approach to addressing the specific issues you've diagnosed.

Project Structure

The project builds across five Parts, with each Part's Unit 5 developing a critical component:

- Part 1: Causal Fairness Toolkit—identifies intervention points through causal analysis.

- Part 2: Pre-Processing Fairness Toolkit—provides data-level interventions targeting representation issues.

- Part 3: In-Processing Fairness Toolkit—integrates fairness directly into model training.

- Part 4: Post-Processing Fairness Toolkit—adjusts model outputs after training.

- Part 5: Fairness Intervention Playbook—synthesizes these components into a cohesive methodology.

Each component builds on the previous ones. Causal analysis reveals where intervention will be most effective. This guides your selection of data, model, or output interventions. All components combine through a pipeline integration strategy in Part 5 that creates coordinated, multi-stage fairness solutions.

Key Questions and Topics

How do we translate conceptual fairness definitions into effective technical interventions?

Fairness definitions must transform into implementable techniques to create real impact. Different definitions require distinct approaches—demographic parity demands different interventions than equal opportunity. The Causal Fairness Toolkit connects abstract definitions to specific causal pathways requiring intervention. The Fairness Intervention Playbook then maps these pathways to appropriate technical solutions. Your choice of intervention shapes who receives loans, housing, or employment opportunities.

Where in the machine learning pipeline should we intervene for maximum impact?

Intervention points span from data preparation through model training to prediction adjustment. Some biases demand data transformation while others require model constraints. The optimal intervention depends on causal understanding—addressing symptoms without targeting causes often fails or creates new problems. The Causal Fairness Toolkit helps you identify whether unfairness stems from data representation, learning algorithms, or decision rules, directing your efforts to the root cause rather than surface manifestations.

What technical approaches best address different types of bias?

Technical interventions fall into three categories: pre-processing (reweighting, transformation), in-processing (constraint optimization, adversarial debiasing), and post-processing (threshold optimization, calibration). Each approach suits different bias patterns and constraints. The Pre-Processing, In-Processing, and Post-Processing Toolkits match techniques to contexts based on empirical effectiveness and theoretical guarantees. This targeted approach replaces the common one-size-fits-all implementations that often fail in practice.

How do we balance fairness improvements against performance trade-offs?

Fairness improvements often require compromises. The interventions frequently decrease accuracy or hurt calibration. The Intervention Playbook's evaluation framework helps you assess trade-offs across fairness metrics, predictive performance, and business objectives. This explicit assessment replaces the common implicit assumption that fairness automatically hurts performance, helping you find the optimal balance for your specific context.

Part Overviews

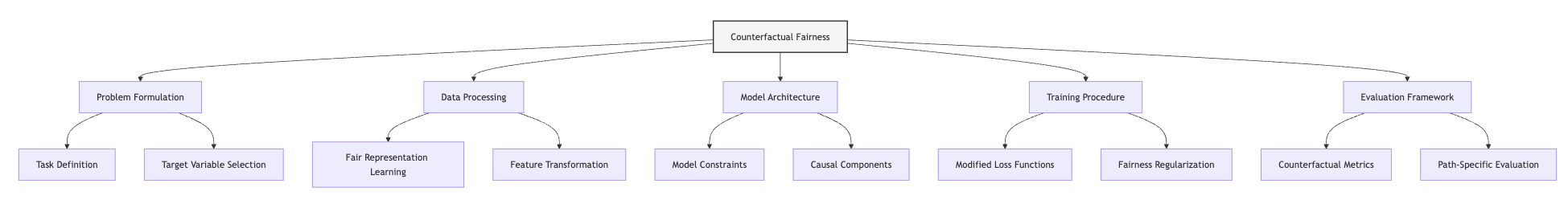

Part 1: Causal Approaches to Fairness examines how causal understanding transforms fairness work. You will analyze unfairness mechanisms, distinguish legitimate predictive relationships from problematic patterns, and develop counterfactual frameworks. This Part culminates in the Causal Fairness Toolkit—a methodology for mapping causal paths between protected attributes and outcomes, identifying optimal intervention points based on causal structure rather than correlations.

Part 2: Data-Level Interventions (Pre-processing) explores addressing bias before model training. You will examine reweighting techniques that adjust sample importance, transformation methods that reduce problematic correlations, and generative approaches that augment underrepresented groups. The Pre-Processing Fairness Toolkit provides decision frameworks for selecting and configuring data-level interventions based on specific bias patterns, helping you fix issues at their source.

Part 3: Model-Level Interventions (In-processing) investigates embedding fairness directly into model training. You will develop constraint optimization techniques, adversarial approaches, and regularization methods. The In-Processing Fairness Toolkit guides selection and implementation of algorithm-level fairness, adapting approaches to different model architectures and training paradigms to create fair learning processes.

Part 4: Prediction-Level Interventions (Post-processing) focuses on adjusting model outputs. You will learn threshold optimization for different fairness criteria, calibration for consistent prediction interpretation, and rejection learning for uncertain predictions. The Post-Processing Fairness Toolkit provides strategies for adjusting predictions without retraining, offering solutions for deployed models where retraining proves impractical or costly.

Part 5: Fairness Intervention Playbook synthesizes previous components into a cohesive methodology. You will integrate pipeline intervention strategies, develop evaluation frameworks, create case studies, and address practical deployment considerations. The complete Fairness Intervention Playbook enables systematic selection and implementation of technical fairness solutions across the ML lifecycle, connecting diagnosis to effective treatment through a principled decision-making process.

Part 1: Causal Approaches to Fairness

Context

Causality transforms fairness work by revealing bias mechanisms that correlational approaches miss.

This Part establishes the foundation for effective bias mitigation. You'll learn to identify root causes of unfairness rather than treating surface symptoms that mislead interventions.

Protected attributes connect to outcomes through multiple causal pathways. Gender might affect loan approvals directly (explicit bias) or indirectly through income differences (structural bias). A credit algorithm showing gender disparities demands causal analysis: Does gender directly influence decisions? Do proxy variables encode discrimination? Or do legitimate risk factors happen to correlate with gender? Causality distinguishes these cases.

Historical patterns embed in data, propagating past discrimination. A hiring algorithm trained on past decisions might penalize career gaps that disproportionately affect women. Causal analysis reveals these patterns, mapping how seemingly neutral variables transmit bias across generations of decisions.

Causal approaches reshape ML systems from data collection through deployment. They guide which variables to collect, how to transform features, which model architectures preserve wanted pathways while blocking unwanted ones, and how to evaluate whether interventions actually improved fairness.

The Causal Fairness Toolkit you'll develop in Unit 5 represents the first component of the Fairness Intervention Playbook. This tool will help you map bias mechanisms to optimal intervention points, ensuring you target causes rather than symptoms.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this Part, you will be able to:

- Analyze causal mechanisms of unfairness in ML systems. You will distinguish direct discrimination from proxy discrimination and spurious correlations, enabling precise diagnosis of how bias enters algorithms.

- Build causal models for algorithmic fairness scenarios. You will construct graphical models depicting relationships between protected attributes and outcomes, moving from vague fairness concerns to testable hypotheses.

- Apply counterfactual fairness principles to ML systems. You will evaluate whether predictions remain consistent in worlds where protected attributes differ, addressing individual fairness beyond group-level metrics.

- Implement practical causal inference techniques despite data limitations. You will extract causal insights from observational data without randomized experiments, addressing the reality that perfect causal knowledge rarely exists.

- Translate causal insights into targeted interventions. You will map causal structures to appropriate technical solutions, selecting interventions that address root causes rather than statistical patterns.

Units

Unit 1

Unit 1: From Correlation to Causation in Fairness

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: Why do traditional statistical fairness metrics often fail to capture genuine discrimination, and how does causality provide a more principled foundation for fairness?

- Question 2: How can causal reasoning help us distinguish between legitimate predictive relationships and problematic patterns that perpetuate historical biases?

Conceptual Context

When working with fairness in AI systems, a fundamental limitation quickly emerges: standard statistical fairness approaches primarily focus on correlations between variables without addressing the underlying causal mechanisms that generate unfair outcomes. This distinction between correlation and causation is not merely a theoretical concern but a critical factor that determines whether your fairness interventions will effectively address the root causes of discrimination or merely treat superficial symptoms.

Consider a hiring algorithm that shows a statistical disparity against female applicants. A correlation-based approach might simply enforce equal selection rates across genders. However, without understanding the causal structure—whether gender directly influences decisions, acts through proxy variables, or shares common causes with qualifications—such interventions may be ineffective or even harmful. As Pearl (2019) notes, "behind every serious attempt to achieve fairness lies a causal model, even if it is not articulated explicitly."

This Unit establishes the foundational understanding of why causality matters for fairness, setting the stage for the more technical causal modeling approaches you'll explore in Units 2-4. By contrasting correlation-based and causal approaches to fairness, you'll develop the conceptual framework necessary to move beyond statistical parity metrics toward interventions that address the genuine causal mechanisms of unfairness. This causal perspective will directly inform the Causal Analysis Methodology you'll develop in Unit 5, enabling you to identify appropriate intervention points based on causal understanding rather than statistical associations.

2. Key Concepts

The Limitations of Correlation-Based Fairness

Traditional fairness metrics in machine learning predominantly focus on statistical correlations between protected attributes and outcomes. This approach, while computationally straightforward, fundamentally limits our ability to identify and address the true sources of discrimination in AI systems. Understanding these limitations is crucial for developing more effective fairness interventions.

Correlation-based fairness metrics like demographic parity, equal opportunity, and equalized odds implicitly treat all statistical associations between protected attributes and outcomes as problematic, without distinguishing between legitimate relationships and discriminatory patterns. This lack of nuance can lead to interventions that "break the thermometer" rather than addressing the underlying "fever" of discrimination.

This concept directly connects to causal fairness approaches by highlighting why we need to move beyond purely statistical associations to understand the generative mechanisms of unfairness. It interacts with other fairness concepts by demonstrating why enforcing statistical constraints without causal understanding can lead to suboptimal or even harmful interventions.

Several researchers have demonstrated the limitations of correlation-based approaches. Hardt et al. (2016) note that enforcing statistical parity without considering causality can harm the very groups we aim to protect by ignoring legitimate predictive differences. Kusner et al. (2017) provide concrete examples where models with identical statistical properties have fundamentally different fairness implications when analyzed through a causal lens.

For example, consider two lending scenarios with identical statistical disparities in approval rates across racial groups:

- In Scenario A, race affects educational opportunities, which legitimately influences credit risk.

- In Scenario B, race directly influences lending decisions independent of credit risk.

These scenarios have identical statistical properties but vastly different fairness implications. Correlation-based metrics cannot distinguish between them, while causal approaches can identify the specific pathways through which discrimination occurs.

For the Causal Analysis Methodology we'll develop in Unit 5, understanding these limitations is essential because it establishes why causal reasoning is necessary for meaningful fairness assessment and intervention. This understanding will guide the development of analysis approaches that look beyond statistical associations to the underlying causal mechanisms.

Causal Models of Discrimination

Causal models provide explicit representations of how discrimination operates through specific mechanisms or pathways in AI systems. This framework is essential for AI fairness because it enables us to distinguish between different types of discrimination that appear statistically identical but require different interventions.

This concept builds on the limitations of correlation-based approaches by providing an alternative framework that explicitly represents how protected attributes influence outcomes through various causal pathways. It interacts with fairness interventions by helping determine where in the ML pipeline to intervene and what type of intervention would most effectively address the specific causal mechanisms present.

Drawing on Pearl's (2009) causal framework, researchers have identified several distinct causal mechanisms of discrimination:

- Direct discrimination occurs when protected attributes directly influence decisions, represented as a direct path from the protected attribute to the outcome in a causal graph.

- Indirect discrimination happens when protected attributes influence decisions through legitimate intermediate variables (e.g., qualification measures that are causally affected by historical discrimination).

- Proxy discrimination arises when decisions depend on variables that are not causally affected by protected attributes but are statistically associated with them due to unmeasured common causes.

Kilbertus et al. (2017) formalized these concepts in their landmark paper, demonstrating how different causal structures necessitate different fairness interventions. For example, proxy discrimination might require removing problematic features, while indirect discrimination could demand more complex interventions that preserve legitimate causal pathways while removing problematic ones.

For our Causal Analysis Methodology, these causal discrimination models provide the foundational framework for identifying what type of discrimination is present in a specific application and selecting appropriate interventions based on these causal structures.

Counterfactual Reasoning for Fairness

Counterfactual reasoning provides a formal framework for asking "what if" questions that capture our intuitive understanding of fairness: would this individual have received the same decision if they belonged to a different demographic group, with all causally unrelated characteristics remaining the same? This approach is central to AI fairness because it directly addresses the core question of whether a system treats people differently based on protected attributes in a causally meaningful way.

This counterfactual perspective builds directly on causal models of discrimination by using them to define precise fairness criteria. It interacts with fairness interventions by providing a clear objective—making model predictions invariant to counterfactual changes in protected attributes along problematic pathways.

Kusner et al. (2017) formalized this approach as "counterfactual fairness," defining a prediction as counterfactually fair if it remains unchanged in counterfactual worlds where an individual's protected attribute is different but all non-descendant variables remain the same. This definition captures the intuition that individuals should not be treated differently based on protected attributes in ways that constitute discrimination.

To illustrate, consider a college admissions example where a qualified female applicant is rejected from a computer science program. Counterfactual fairness asks: would this same applicant have been rejected if they were male, holding constant all characteristics not causally dependent on gender? If the answer is no, the decision exhibits counterfactual unfairness.

The key insight from counterfactual fairness is that not all influences of protected attributes constitute discrimination. As Kusner et al. (2017) argue, only some causal pathways from protected attributes to outcomes represent unfair influence, while others may represent legitimate relationships that should be preserved.

For our Causal Analysis Methodology, counterfactual reasoning provides both a formal fairness criterion that can guide intervention selection and a framework for evaluating whether existing systems exhibit causal forms of discrimination.

Intervention Points From a Causal Perspective

Causal reasoning enables the identification of optimal intervention points throughout the ML pipeline based on understanding the specific mechanisms that generate unfairness. This concept is crucial for AI fairness because different causal structures demand different intervention strategies—interventions that work for one type of discrimination may be ineffective or harmful for others.

This intervention perspective builds on causal models and counterfactual reasoning by translating causal understanding into concrete decisions about where and how to intervene in the ML pipeline. It connects directly to the pre-processing, in-processing, and post-processing techniques you'll explore in subsequent Parts by providing a principled basis for choosing between them.

Research by Zhang and Bareinboim (2018) demonstrates how different causal structures necessitate different intervention approaches. For direct discrimination, removing protected attributes or applying constraints during model training might be appropriate. For proxy discrimination, transforming features that serve as proxies might be needed. For selection bias, addressing data collection processes could be essential.

For example, in a hiring scenario where gender affects career gaps which affect hiring decisions:

- If we determine career gaps are legitimate predictors of job performance, we might focus on addressing underlying societal factors while preserving the feature.

- If career gaps are not causally related to performance but merely associated with gender, we might remove or transform this feature.

- If career gaps sometimes matter for performance (in some jobs but not others), we might need more nuanced interventions that preserve some pathways while blocking others.

These intervention decisions cannot be made based on statistical associations alone—they require causal understanding of how different variables relate to each other and to the outcome of interest.

For our Causal Analysis Methodology, this intervention perspective will provide the bridge between causal analysis and specific intervention techniques, helping practitioners select appropriate fairness approaches based on the causal structures identified in their specific applications.

Domain Modeling Perspective

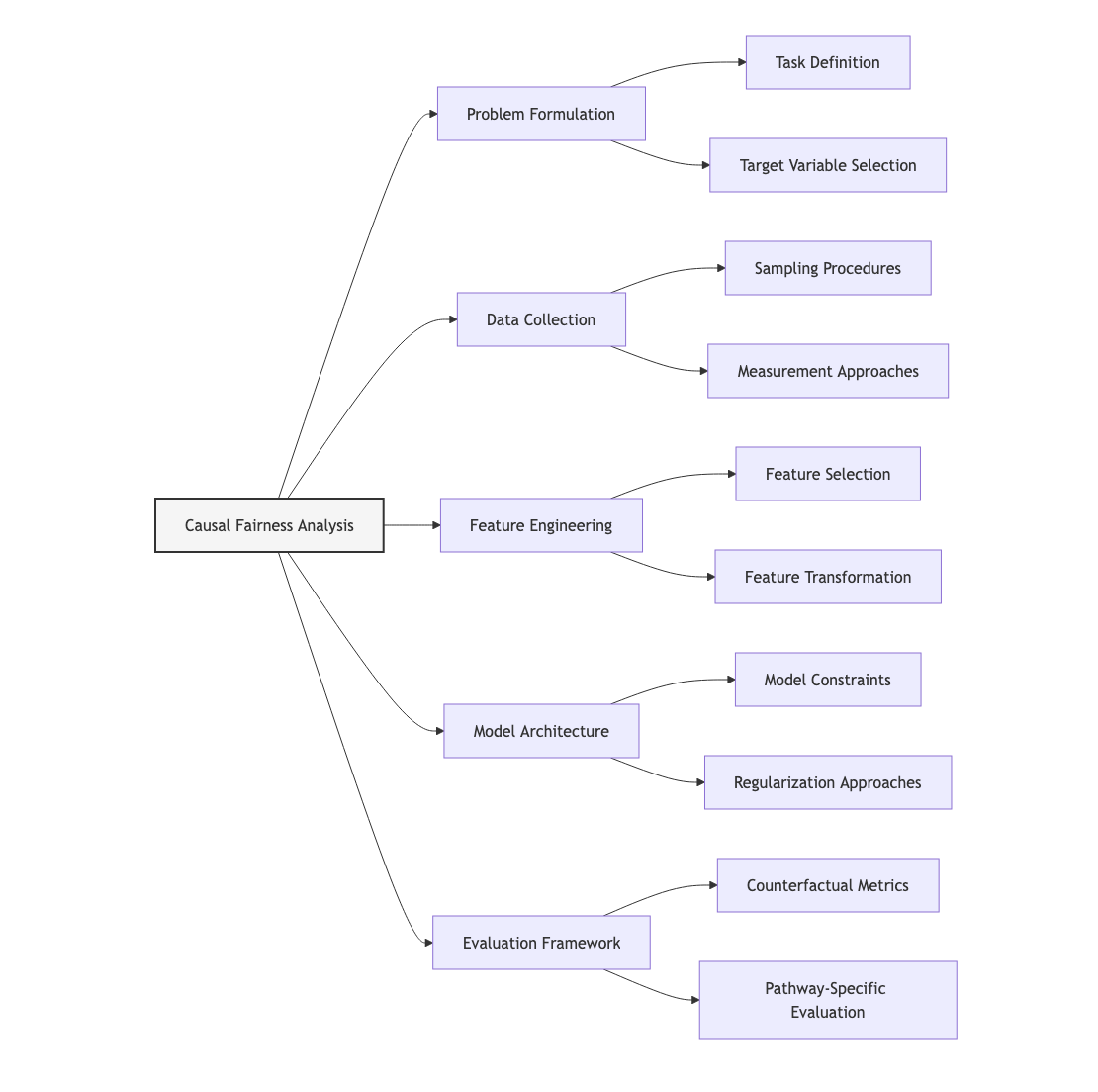

From a domain modeling perspective, causal approaches to fairness map to specific components of ML systems:

- Problem Formulation: Causal analysis reveals how the very definition of the prediction task may embed discriminatory assumptions, potentially suggesting reformulation of the problem itself.

- Data Collection: Causal understanding highlights how sampling procedures and measurement approaches may introduce biases through selection or collider effects.

- Feature Engineering: Causal models distinguish between features that serve as legitimate predictors versus problematic proxies for protected attributes.

- Model Architecture: Causal structures inform which model constraints or regularization approaches might effectively address the specific discrimination mechanisms present.

- Evaluation Framework: Counterfactual fairness provides evaluation criteria that align with causal understanding rather than purely statistical associations.

This domain mapping helps you understand how causal considerations influence different stages of the ML lifecycle rather than viewing them as abstract theoretical frameworks. The Causal Analysis Methodology you'll develop in Unit 5 will leverage this mapping to create structured approaches for identifying causal discrimination and determining appropriate interventions throughout the ML pipeline.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract causal concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Correlation vs. causation in fairness is similar to the difference between treating symptoms versus curing a disease in medicine. A physician who only addresses symptoms (fever, pain) without understanding the underlying disease mechanism might provide temporary relief but fail to cure the patient. Similarly, fairness interventions that only address statistical disparities without understanding causal mechanisms might temporarily improve metrics but fail to address the root causes of discrimination.

- Causal models of discrimination function like architectural blueprints that reveal the internal structure of a building. Just as blueprints show which walls are load-bearing (critical) versus decorative (non-essential), causal models reveal which connections between variables represent fundamental mechanisms of discrimination versus mere correlations. This distinction matters because modifying load-bearing walls without proper support could collapse the structure, while interventions that ignore causal structure might compromise model performance or fail to address fundamental sources of bias.

- Counterfactual reasoning resembles a controlled scientific experiment where researchers change exactly one variable while keeping others constant. When scientists test a new drug, they create identical test groups and change only the treatment variable—this allows them to conclude that differences in outcomes are caused by the treatment rather than other factors. Similarly, counterfactual fairness examines what would happen if only a person's protected attribute changed while everything causally independent remained constant, isolating whether protected attributes unfairly influence decisions.

- Intervention points from a causal perspective can be compared to water quality management for a city. Water quality issues can arise at different points—contamination at the source, problems in the treatment plant, or issues in the distribution network. Each requires different interventions: watershed protection at the source, chemical treatment at the plant, or pipe replacement in the distribution system. Similarly, fairness issues can originate at different points in the ML pipeline—data collection, feature engineering, or model training—each requiring different intervention strategies.

Intersectionality Consideration

Causal approaches to fairness must explicitly address how multiple protected attributes interact to create unique causal mechanisms that affect individuals with overlapping marginalized identities. Traditional causal models often examine protected attributes in isolation, potentially missing critical intersectional effects where multiple attributes combine to create distinct causal pathways.

As Crenshaw (1989) established in her foundational work on intersectionality, discrimination often operates differently at the intersections of multiple marginalized identities, creating unique challenges that single-attribute analyses miss. For AI systems, this means causal fairness approaches must examine how multiple protected attributes jointly influence outcomes through various causal pathways.

Recent work by Yang et al. (2020) demonstrates how causal modeling can be extended to capture intersectional effects by explicitly representing interaction terms in structural equations and examining path-specific effects across demographic intersections. Their approach enables more nuanced analysis of how multiple attributes jointly influence outcomes through various causal pathways.

For instance, a recommendation algorithm for academic opportunities might exhibit a unique causal pattern of discrimination against Black women that differs from patterns affecting either Black men or white women. Standard causal models examining race and gender separately would miss this intersectional effect, while an intersectional causal approach would reveal the specific pathways through which this discrimination operates.

For our Causal Analysis Methodology, addressing intersectionality requires:

- Explicitly modeling interactions between protected attributes in causal graphs.

- Examining counterfactual fairness across demographic intersections rather than for single attributes in isolation.

- Identifying causal pathways that specifically affect intersectional groups.

- Designing intervention strategies that address the unique causal mechanisms operating at demographic intersections.

By incorporating these intersectional considerations, our methodology will enable more comprehensive causal analysis that captures the complex ways in which multiple forms of discrimination interact rather than treating protected attributes as independent factors.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To effectively apply causal reasoning to fairness in practice, follow this structured methodology:

-

Discrimination Mechanism Identification:

-

Examine potential direct discrimination paths: Does the protected attribute directly influence decisions?

- Analyze indirect discrimination through mediators: Do protected attributes affect legitimate intermediate factors?

- Investigate proxy discrimination: Do decisions depend on variables that correlate with protected attributes due to unmeasured common causes?

-

Document potential discrimination mechanisms with accompanying evidence and reasoning.

-

Causal Fairness Criteria Selection:

-

Determine whether the application calls for group-level or individual-level causal fairness.

- Select appropriate counterfactual fairness definitions based on application context and stakeholder requirements.

- Identify which causal pathways should be considered fair versus unfair based on domain knowledge and ethical principles.

-

Document fairness criteria selection and justification, including ethical reasoning.

-

Preliminary Causal Analysis:

-

Draw on domain expertise to sketch initial causal graphs representing relationships between protected attributes, features, and outcomes.

- Identify potential confounders and mediators in these relationships.

- Formulate testable implications of these causal structures.

- Document assumptions and uncertainties in the causal model.

These methodologies integrate with standard ML workflows by informing initial problem formulation, data collection strategies, feature engineering decisions, and modeling approaches before technical implementation begins. While they add complexity to the development process, they establish a more solid foundation for effective fairness interventions.

Implementation Challenges

When applying causal reasoning to fairness, practitioners commonly face these challenges:

-

Limited Causal Knowledge: Most applications lack perfect understanding of the true causal structures. Address this by:

-

Starting with multiple plausible causal models based on domain expertise.

- Performing sensitivity analysis to determine how conclusions change under different causal assumptions.

- Adopting an iterative approach that refines causal understanding over time based on observed outcomes.

-

Being transparent about causal assumptions and their limitations.

-

Tension Between Causal Fairness and Model Performance: Eliminating problematic causal pathways may reduce predictive accuracy. Address this by:

-

Making explicit the trade-offs between different objectives.

- Exploring interventions that specifically target problematic pathways while preserving legitimate predictive relationships.

- Communicating performance implications to stakeholders and establishing acceptable trade-off thresholds.

- Considering whether the prediction task itself needs reframing if fairness and performance seem fundamentally at odds.

Successfully implementing causal fairness approaches requires resources including domain expertise to inform causal models, stakeholder engagement to establish which causal pathways are considered fair versus unfair, and organizational willingness to potentially sacrifice some predictive performance for improved fairness properties.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your causal fairness analysis is effective, implement these evaluation strategies:

-

Causal Assumption Validation:

-

Test implied conditional independencies in your causal model against observed data.

- Perform sensitivity analysis to determine how robust your conclusions are to variations in causal assumptions.

- Seek expert review of causal models to validate their plausibility from domain perspectives.

-

Document the evidence supporting key causal relationships in your model.

-

Counterfactual Fairness Assessment:

-

Evaluate whether predictions remain consistent under counterfactual changes to protected attributes.

- Measure the magnitude of counterfactual unfairness when present.

- Assess counterfactual fairness across different demographic subgroups and intersections.

- Compare counterfactual fairness with traditional statistical fairness metrics to identify discrepancies.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated with your organization's broader fairness assessment framework, providing deeper insights than purely statistical metrics while acknowledging the limitations of causal knowledge in practical applications.

4. Case Study: College Admissions Algorithm

Scenario Context

A university is developing a machine learning algorithm to help predict which applicants are likely to succeed in its computer science program, hoping to streamline the admissions process. The algorithm analyzes high school performance, standardized test scores, extracurricular activities, recommendation letters, and demographic information to predict first-year GPA and graduation likelihood.

Initial evaluation revealed concerning disparities: the algorithm recommends male applicants at significantly higher rates than female applicants with seemingly similar qualifications. The university's data science team must determine whether this disparity represents genuine discrimination and, if so, how to address it effectively.

This scenario involves multiple stakeholders with different priorities: admissions officers seeking to identify successful students, faculty concerned about maintaining academic standards, university leadership focused on diversity goals, and prospective students hoping for fair evaluation. The fairness implications are significant given the potential impact on educational opportunities and career trajectories.

Problem Analysis

Applying a causal perspective reveals several potential mechanisms behind the observed gender disparity:

- Direct Discrimination: The model might be directly using gender as a feature, creating a direct causal path from gender to admissions decisions. However, the team verified that gender was explicitly excluded from the model's features, making this explanation unlikely.

- Proxy Discrimination: Several features might serve as proxies for gender, creating indirect paths from gender to admissions decisions. For example, the model heavily weights participation in competitive programming contests, which historically have much higher male participation due to societal factors unrelated to CS aptitude. Similarly, it values certain technical hobbies that have been culturally associated with males, creating statistical associations between these activities and gender through unmeasured common causes like social expectations.

- Indirect Discrimination through Legitimate Pathways: Gender might influence certain legitimate predictors of CS success. For example, research suggests that due to stereotype threat, female students might underperform on standardized technical tests despite having equivalent underlying abilities. This creates a causal path from gender to test scores to admissions decisions that represents a form of indirect discrimination.

- Selection Bias in Training Data: The historical admissions data used to train the model reflects past discriminatory practices, creating a biased sample that doesn't represent the true relationship between qualifications and academic success across genders.

A correlation-based approach might simply enforce equal selection rates across genders, potentially admitting less-qualified applicants or rejecting qualified ones. In contrast, a causal approach would identify the specific mechanisms creating discrimination and target interventions accordingly.

From an intersectional perspective, the analysis becomes more complex. The team discovered that the disparity was particularly pronounced for women from underrepresented racial backgrounds and lower socioeconomic status, suggesting unique causal mechanisms affecting these intersections that would not be captured by examining gender alone.

Solution Implementation

To address these issues through a causal approach, the university implemented a structured analysis:

- Causal Modeling: The team collaborated with domain experts to develop a causal graph representing relationships between applicant characteristics, connecting variables like gender, socioeconomic background, educational opportunities, extracurricular activities, test performance, and predicted academic success. This model explicitly represented both legitimate predictive relationships and potentially problematic pathways.

- Counterfactual Analysis: Using this causal model, they performed counterfactual analysis asking: "Would this applicant receive the same prediction if they were a different gender, with all causally unrelated characteristics held constant?" This analysis revealed significant counterfactual unfairness, confirming that the model treated otherwise identical applicants differently based on gender.

-

Pathway Identification: Further analysis identified specific problematic pathways in the model:

-

Heavy reliance on participation in specific extracurricular activities that are culturally associated with gender

- Emphasis on recommendation letter language that differs systematically across genders due to writer biases

-

Overweighting of standardized test components where stereotype threat affects performance

-

Intervention Planning: Based on this causal understanding, the team planned targeted interventions:

-

Rather than simply enforcing demographic parity or removing gender from the dataset, they identified specific features serving as problematic proxies

- For legitimate predictors affected by gender through unfair mechanisms, they developed adjustments based on causal understanding

- They redesigned the prediction task itself to focus on variables less susceptible to discriminatory influences

This causal approach allowed the university to maintain predictive accuracy for academic success while addressing the specific mechanisms creating gender discrimination, rather than implementing crude statistical adjustments that might have undermined the algorithm's effectiveness.

Outcomes and Lessons

The causal approach yielded several key benefits compared to a purely statistical intervention:

- It preserved legitimate predictive relationships while addressing specific discriminatory pathways, maintaining model performance while improving fairness.

- It revealed unique challenges at intersections of gender, race, and socioeconomic status that would have been missed by single-attribute analysis.

- It provided an explainable foundation for fairness interventions that stakeholders could understand and accept based on causal reasoning rather than abstract statistical properties.

Key challenges included the difficulty of validating causal assumptions with limited experimental data and navigating disagreements about which causal pathways represented legitimate versus problematic influences.

The most generalizable lessons included:

- The importance of distinguishing between different causal mechanisms of discrimination rather than treating all statistical disparities as equally problematic.

- The value of counterfactual reasoning in providing an intuitive and principled definition of fairness that stakeholders could understand and support.

- The necessity of pathway-specific interventions that target problematic causal mechanisms while preserving legitimate predictive relationships.

These insights directly inform the development of the Causal Analysis Methodology in Unit 5, demonstrating how causal understanding enables more targeted and effective fairness interventions compared to purely statistical approaches.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Correlation Vs. Causation in Practice

Q: How does the distinction between correlation and causation practically impact my fairness interventions?

A: The correlation-causation distinction fundamentally changes which interventions will effectively address unfairness. Consider a lending algorithm showing racial disparities in approval rates. A correlation-based approach might enforce demographic parity by adjusting approval thresholds across races, potentially approving underqualified applicants or rejecting qualified ones. In contrast, a causal approach first identifies why the disparity exists: Is it direct discrimination? Proxy discrimination through seemingly neutral variables like zip codes? Indirect discrimination through legitimately predictive variables affected by historical inequities? Or selection bias in training data? Each causal mechanism requires different interventions: removing problematic features for proxy discrimination, collecting more representative data for selection bias, or developing more nuanced approaches for indirect discrimination. Without causal understanding, your interventions might inadvertently harm the groups you're trying to protect or create new fairness problems while addressing surface symptoms. Simply put, treating fairness as a purely statistical property is like prescribing medication without diagnosing the disease—you might temporarily relieve symptoms while failing to address the underlying condition.

FAQ 2: Causal Knowledge Requirements

Q: Do I need perfect causal knowledge to apply these approaches, and if not, how can I handle uncertainty about the true causal structure?

A: Perfect causal knowledge is rarely available in practice, but this doesn't prevent you from applying causal reasoning to fairness. Instead, adopt a systematic approach to handling causal uncertainty: First, develop multiple plausible causal models based on domain expertise, existing research, and stakeholder input rather than assuming a single "true" model. Second, perform sensitivity analysis to understand how your conclusions change under different causal assumptions—if several plausible models lead to similar intervention recommendations, you can proceed with greater confidence. Third, implement conservative interventions that address fairness issues under multiple causal scenarios rather than optimizing for a single assumed structure. Fourth, design your system for continuous learning, incorporating new evidence to refine causal understanding over time. Finally, maintain transparency about causal assumptions and their limitations in documentation and communications. This approach acknowledges uncertainty while still leveraging the considerable benefits of causal reasoning compared to purely associational approaches. Remember that even imperfect causal models often provide better guidance for fairness interventions than no causal reasoning at all.

6. Project Component Development

Component Description

In Unit 5, you will develop the preliminary causal analysis section of the Causal Analysis Methodology. This component will provide a structured approach for identifying potential causal mechanisms of discrimination and performing initial counterfactual analysis before developing formal causal models in subsequent Units.

The deliverable will take the form of an analysis template with guided questions, documentation formats, and initial causal assessment frameworks that will be expanded through the modeling techniques you'll learn in Units 2-4.

Development Steps

- Create a Discrimination Mechanism Identification Framework: Develop a structured questionnaire that guides users through identifying potential direct, indirect, and proxy discrimination mechanisms in their specific application domain. Include prompts about how protected attributes might influence decisions through various causal pathways.

- Build a Counterfactual Formulation Template: Design a template for formulating relevant counterfactual questions that assess whether prediction outcomes would change under different protected attribute values. Include guidance on documenting counterfactual scenarios and their fairness implications.

- Develop an Initial Causal Diagram Approach: Create guidelines for sketching preliminary causal diagrams representing relationships between protected attributes, features, and outcomes based on domain knowledge. Include annotation conventions for documenting assumptions, uncertainties, and potential discrimination pathways.

Integration Approach

This preliminary component will interface with other parts of the Causal Analysis Methodology by:

- Providing the initial discrimination mechanism identification that will be formalized through the causal modeling in Unit 2.

- Establishing the counterfactual questions that will be analyzed using the formal framework from Unit 3.

- Creating preliminary causal diagrams that will be refined through the inference techniques from Unit 4.

To enable successful integration, document assumptions explicitly, use consistent terminology across components, and create clear connections between the preliminary analysis and the more formal techniques that will be applied in subsequent Units.

7. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

This Unit has established the fundamental distinction between correlation-based and causal approaches to fairness. Key insights include:

- Statistical fairness metrics have inherent limitations because they operate purely on correlations without distinguishing between different mechanisms of discrimination. This limitation often leads to interventions that address symptoms rather than root causes of unfairness.

- Causal models of discrimination provide a more principled framework by explicitly representing how protected attributes influence outcomes through various pathways. This causal perspective enables us to distinguish between direct, indirect, and proxy discrimination—distinctions that are invisible to purely statistical approaches.

- Counterfactual reasoning offers an intuitive and powerful approach to fairness by asking whether predictions would change if protected attributes were different while holding causally unrelated characteristics constant. This approach captures our ethical intuitions about discrimination more effectively than statistical parity metrics.

- Intervention selection should be guided by causal understanding, with different discrimination mechanisms requiring different mitigation strategies. This targeted approach enables more effective interventions with fewer negative side effects compared to blanket statistical constraints.

These concepts directly address our guiding questions by explaining why causal reasoning provides a more principled foundation for fairness and how it helps distinguish between legitimate predictive relationships and problematic patterns that perpetuate bias.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Begin by questioning whether observed disparities represent genuine discrimination or legitimate predictive relationships, rather than automatically treating all statistical associations as problematic.

- Draw on domain knowledge to identify potential causal pathways through which protected attributes might influence outcomes, distinguishing between direct, indirect, and proxy discrimination.

- Formulate relevant counterfactual questions to assess whether your system would treat individuals differently based on protected attributes with all else causally equal.

- Use causal understanding to guide intervention selection, targeting the specific mechanisms creating unfairness rather than applying generic statistical constraints.

If you're new to causal reasoning, start with simple causal diagrams representing your domain knowledge about how variables relate to each other. Even basic causal sketches can provide valuable insights beyond purely correlational approaches. As your causal understanding develops, you can incorporate more sophisticated techniques.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will build on this conceptual foundation by exploring formal techniques for constructing causal models to represent discrimination mechanisms. You will learn to translate domain knowledge into explicit causal graphs and structural equations that systematically represent how bias enters and propagates through AI systems.

The conceptual understanding you've developed in this Unit will provide the foundation for these more technical modeling approaches. By understanding why causality matters for fairness, you're now prepared to learn how to construct and analyze formal causal models that can guide concrete fairness interventions.

References

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167.

Hardt, M., Price, E., & Srebro, N. (2016). Equality of opportunity in supervised learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 3315-3323).

Kilbertus, N., Carulla, M. R., Parascandolo, G., Hardt, M., Janzing, D., & Schölkopf, B. (2017). Avoiding discrimination through causal reasoning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 656-666).

Kusner, M. J., Loftus, J., Russell, C., & Silva, R. (2017). Counterfactual fairness. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 4066-4076).

Pearl, J. (2009). Causality: Models, reasoning and inference (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Pearl, J. (2019). The seven tools of causal inference, with reflections on machine learning. Communications of the ACM, 62(3), 54-60.

Yang, K., Loftus, J. R., & Stoyanovich, J. (2020). Causal intersectionality for fair ranking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.08688.

Zhang, J., & Bareinboim, E. (2018). Fairness in decision-making – the causal explanation formula. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 32, No. 1).

Unit 2

Unit 2: Building Causal Models for Bias Detection

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How can we systematically translate domain knowledge into formal causal models that accurately represent the mechanisms through which bias enters and propagates in AI systems?

- Question 2: What practical approaches enable us to identify and validate critical causal pathways between protected attributes and outcomes that may generate unfairness in machine learning models?

Conceptual Context

Understanding the causal mechanisms that generate bias in AI systems is essential for effective intervention. While Unit 1 established why causal reasoning matters for fairness, this Unit focuses on how to construct explicit causal models that represent these mechanisms. Without formal causal representations, fairness efforts may target symptoms rather than root causes, leading to interventions that fail to address fundamental sources of bias or inadvertently create new fairness problems.

Causal models provide the structural foundation for fairness analysis by explicitly representing how protected attributes influence outcomes through various pathways. As Pearl (2009) notes, "behind every serious claim of discrimination lies a causal model, and behind every successful policy to correct discrimination lies a causal understanding that recognizes which pathways need to be altered and which are best left unaltered." When you build explicit causal models for bias detection, you transform implicit assumptions about discrimination into testable structures that can guide targeted interventions.

This Unit builds directly on the conceptual understanding of causality from Unit 1, providing you with concrete techniques for constructing causal graphs and structural equation models that represent bias mechanisms. These modeling approaches will enable you to distinguish between different types of discrimination, identify appropriate intervention points, and evaluate counterfactual scenarios in Units 3 and 4. The formal causal models you learn to build here will directly inform the Causal Analysis Methodology you'll develop in Unit 5, providing the structural foundation for detecting and addressing bias throughout the ML lifecycle.

2. Key Concepts

Causal Graph Construction

Causal graphs provide a formal representation of how variables in an AI system influence one another, enabling systematic analysis of the mechanisms through which bias enters and propagates. This concept is crucial for AI fairness because graphs make explicit the pathways through which protected attributes affect outcomes, allowing you to distinguish between legitimate predictive relationships and problematic discrimination patterns.

A causal graph is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) where nodes represent variables and edges represent direct causal relationships between them. In the fairness context, these graphs typically include protected attributes (e.g., race, gender), features used by the model, outcome variables, and potential confounders or mediators. By depicting the causal structure explicitly, these graphs enable you to identify direct discrimination (paths directly from protected attributes to outcomes), indirect discrimination (paths through mediators), and proxy discrimination (relationships through shared ancestors).

Causal graph construction interacts with the fairness definitions explored in previous Units by providing the structural foundation for counterfactual fairness analysis. These graphs directly inform which intervention approaches might be most effective by revealing where in the causal structure bias enters the system.

Pearl's causal framework provides a formal basis for constructing these graphs (Pearl, 2009), while recent work by Plečko and Bareinboim (2022) has extended this approach specifically for fairness analysis. Their research demonstrates how different graph structures correspond to different types of fairness violations and appropriate intervention strategies, providing a comprehensive framework for causal fairness analysis based on graph properties.

For example, consider a hiring algorithm where gender might influence hiring decisions. A causal graph would explicitly represent whether gender directly affects decisions (direct discrimination), influences intermediate variables like employment gaps that affect decisions (indirect discrimination), or is merely correlated with decisions through common causes like field of study (proxy discrimination). Each of these structures has different implications for what constitutes an appropriate fairness intervention.

For the Causal Analysis Methodology we'll develop in Unit 5, causal graphs provide the essential structural representation that enables systematic identification of bias sources and appropriate intervention points. By learning to construct these graphs, you'll gain the fundamental skill needed for all subsequent causal fairness analysis.

Identifying Causal Variables and Relationships

Constructing effective causal models requires systematic approaches for identifying relevant variables and determining the causal relationships between them. This concept is essential for AI fairness because the variables you include in your model and the relationships you specify directly determine which bias mechanisms the model can represent and which remain invisible.

This variable and relationship identification builds on causal graph construction by providing concrete methodologies for populating those graphs with appropriate nodes and edges. It interacts with the fairness definitions from previous Units by determining which pathways of influence can be represented and analyzed in your causal model.

The process involves several key steps: identifying protected attributes relevant to your fairness concerns; determining outcome variables that represent decision points where fairness matters; specifying mediators through which protected attributes might influence outcomes; and including confounders that affect both protected attributes and outcomes, potentially creating spurious correlations.

Loftus et al. (2018) provide a framework for this process in their work on causal reasoning for algorithmic fairness. They demonstrate techniques for variable identification based on domain knowledge, data analysis, and fairness requirements. Their approach emphasizes the importance of including variables that might reveal indirect discrimination or proxy effects, not just those directly used in the model.

For example, in a lending algorithm, relevant variables might include protected attributes (race, gender), outcomes (loan approval), mediators (credit score, income), and confounders (neighborhood characteristics, economic conditions). Relationships between these variables would be determined through domain expertise, existing research, and potentially causal discovery techniques applied to data.

For our Causal Analysis Methodology, systematic variable and relationship identification is essential because it determines the scope and accuracy of the resulting causal model. A model missing critical variables or relationships might fail to detect important bias mechanisms, while one including irrelevant elements might become unnecessarily complex or misleading.

Structural Equation Models for Bias Representation

Structural equation models (SEMs) provide a mathematical formalization of causal relationships that enable precise specification and analysis of bias mechanisms. This concept is vital for AI fairness because SEMs go beyond graphical representations to quantify how variables influence each other, allowing for more detailed analysis and precise intervention design.

SEMs build on causal graphs by adding mathematical equations that specify the functional relationships between variables, transforming qualitative causal structures into quantitative models. They interact with counterfactual fairness by providing the mathematical foundation for generating and evaluating counterfactual scenarios.

A structural equation model consists of equations defining how each variable is determined by its direct causes (parents in the causal graph) plus an error term representing unmeasured factors. In the fairness context, these equations allow you to model how protected attributes influence other variables through various pathways and with different strengths.

Kusner et al. (2017) employ SEMs as the foundation for counterfactual fairness in their landmark paper. They demonstrate how these models enable precise definition of counterfactual scenarios by showing how interventions on protected attributes would propagate through the system according to the specified causal structure.

For example, a SEM for a college admissions scenario might include equations specifying how gender influences standardized test scores through stereotype threat, how socioeconomic background affects educational opportunities, and how these factors collectively determine admission outcomes. These equations would quantify the strength of each relationship, enabling precise analysis of how bias propagates through the system.

For our Causal Analysis Methodology, SEMs provide the mathematical precision needed to move beyond qualitative causal reasoning to quantitative analysis and intervention design. By learning to develop these models, you'll gain the ability to specify exactly how bias operates in your system and design precisely targeted interventions.

Validating Causal Models in Fairness Contexts

Validating causal models is essential to ensure they accurately represent the actual mechanisms generating bias in AI systems. This concept is critical for AI fairness because interventions based on incorrect causal models may fail to address the real sources of bias or might inadvertently introduce new fairness problems.

Validation builds on causal graph construction and SEM development by providing approaches to assess whether these models accurately represent reality. It interacts with intervention design by determining how much confidence we can place in the causal understanding guiding our fairness strategies.

Validation approaches include testing implied conditional independencies (relationships that should be statistically independent according to the causal structure), comparing model predictions against experimental or observational data, sensitivity analysis to assess how robust conclusions are to violations of causal assumptions, and leveraging domain expertise to evaluate model plausibility.

Kilbertus et al. (2020) demonstrate the importance of causal model validation in their work on causal fairness analysis. They show how incorrect causal assumptions can lead to interventions that fail to address discrimination or inadvertently create new fairness problems, emphasizing the need for rigorous validation practices.

For example, if your causal model implies that education level and zip code should be conditionally independent given income, you can test this implication against your data. Significant deviation from this expected independence might suggest your causal structure needs revision. Similarly, if your model predicts certain effects from interventions, you might validate these predictions against historical outcomes from similar interventions.

For our Causal Analysis Methodology, validation techniques provide essential quality control, ensuring that the causal understanding guiding fairness interventions is well-founded. By incorporating these approaches, you'll be able to develop more reliable causal models and have greater confidence in the resulting fairness strategies.

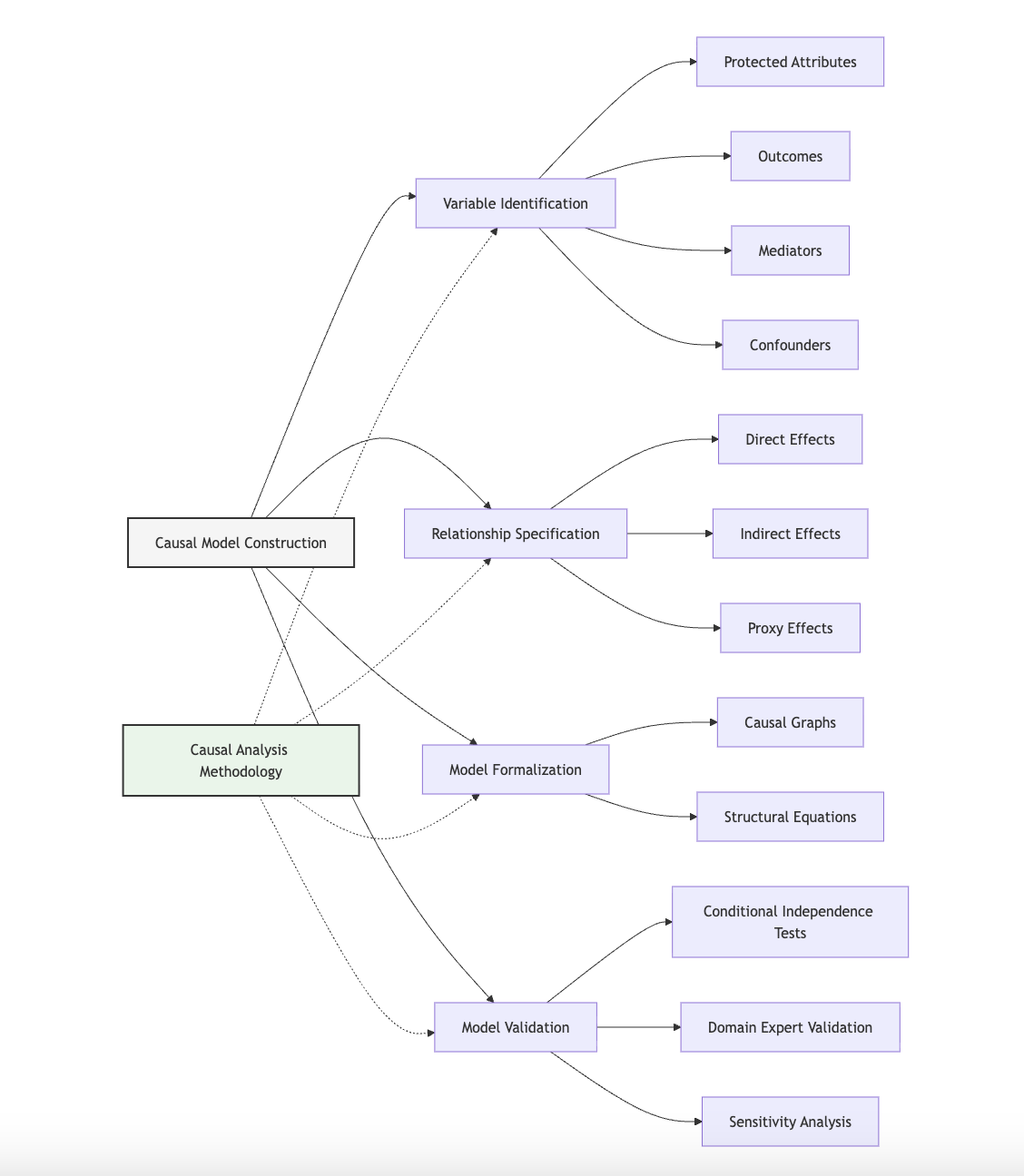

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, causal model construction maps to specific components of ML systems:

- Data Collection and Selection: Causal models reveal which variables are necessary to measure for comprehensive bias analysis, identifying potential selection biases or missing confounders.

- Feature Engineering: Causal structures distinguish between features that serve as legitimate predictors versus proxies for protected attributes, informing feature selection and transformation.

- Model Architecture: Causal understanding guides which relationships should be learned versus which should be constrained, informing model design decisions.

- Evaluation Framework: Causal models provide the foundation for counterfactual evaluation approaches that assess fairness based on causal understanding.

- Intervention Design: Causal structures identify where in the ML pipeline interventions should be targeted to effectively address bias mechanisms.

This domain mapping helps you connect abstract causal modeling concepts to concrete ML system components. The Causal Analysis Methodology you'll develop in Unit 5 will leverage this mapping to guide where and how to implement fairness interventions based on causal understanding.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract causal modeling concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Causal graph construction is similar to creating architectural blueprints before building a house. Just as blueprints specify how rooms connect and where utilities flow, causal graphs specify how variables influence each other and where bias might propagate. Without proper blueprints, construction proceeds haphazardly, potentially creating structural problems that are expensive to fix later. Similarly, without proper causal graphs, fairness interventions proceed without clear understanding of bias mechanisms, potentially creating new problems or failing to address root causes. Just as blueprints evolve through multiple drafts based on function, constraints, and expert feedback, causal graphs evolve through iterative refinement based on data, domain knowledge, and fairness requirements.

- Variable and relationship identification resembles diagnosing a complex medical condition, where physicians must determine which symptoms, risk factors, and test results are relevant and how they relate to each other. A doctor who overlooks key symptoms or misunderstands their relationships might miss the correct diagnosis or prescribe ineffective treatments. Similarly, causal modeling that omits critical variables or misspecifies their relationships might fail to identify important bias mechanisms or lead to misguided interventions. Just as medical diagnosis integrates patient history, current symptoms, test results, and medical knowledge, causal modeling integrates historical patterns, current data, statistical analysis, and domain expertise.

- Structural equation models function like recipe instructions that specify not just what ingredients are needed (variables) but exactly how they combine and in what proportions (functional relationships). A recipe that lists ingredients without specific measurements or mixing instructions leaves too much ambiguity for reliable results. Similarly, causal graphs without structural equations show which variables influence each other but not how strongly or in what functional form, limiting their utility for precise analysis or intervention design. Just as detailed recipes enable you to predict how changes to ingredients will affect the final dish, SEMs enable you to predict how interventions on certain variables will affect outcomes throughout the system.

- Causal model validation resembles stress-testing a bridge design before construction begins. Engineers don't simply trust that their blueprints will produce a safe bridge; they subject the design to various tests and scenarios to verify its structural integrity. Similarly, causal models shouldn't be accepted based solely on their theoretical plausibility; they should be validated against data, tested for robustness to assumption violations, and evaluated by domain experts. Just as bridge stress-testing identifies potential failure points before they become dangerous, causal model validation identifies potential inaccuracies before they lead to misguided fairness interventions.

Intersectionality Consideration

Causal modeling for bias detection must explicitly address intersectionality – how multiple protected attributes interact to create unique causal mechanisms affecting individuals with overlapping marginalized identities. Standard causal models that examine protected attributes in isolation may miss critical intersectional effects where multiple dimensions of identity create distinct causal pathways.

Traditional causal graphs typically represent protected attributes as separate nodes with independent causal relationships. This approach fails to capture how the intersection of multiple attributes might create unique mechanisms that differ from those affecting any single attribute in isolation. For example, bias against Black women in facial recognition systems might operate through causal pathways distinct from those affecting either Black men or white women.

Recent work by Yang et al. (2020) proposes approaches for constructing "intersectional causal graphs" that explicitly model how multiple protected attributes jointly influence outcomes. Their research demonstrates techniques for representing interaction effects between protected attributes in causal models, enabling more nuanced analysis of bias mechanisms that specifically affect intersectional groups.

For the Causal Analysis Methodology, addressing intersectionality in causal modeling requires:

- Explicitly representing intersectional categories as distinct nodes in causal graphs when appropriate

- Modeling interaction terms between protected attributes in structural equations

- Testing for path-specific effects that uniquely affect intersectional subgroups

- Validating causal models with specific attention to their performance for intersectional categories

By incorporating these intersectional considerations into causal model construction, you'll develop more comprehensive representations of bias mechanisms that capture the complex ways multiple forms of discrimination interact rather than treating protected attributes as independent factors.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To systematically construct causal models for bias detection, follow this structured methodology:

-

Variable Identification and Classification:

-

Identify protected attributes relevant to your fairness concerns (e.g., race, gender, age).

- Specify outcome variables representing decisions where fairness matters (e.g., loan approval, hiring recommendation).

- Identify potential mediators through which protected attributes might influence outcomes (e.g., education, test scores).

- Determine possible confounders that affect both protected attributes and outcomes (e.g., neighborhood characteristics, socioeconomic factors).

-

Categorize each variable according to its role in the causal structure and document your reasoning.

-

Causal Relationship Mapping:

-

Draw on domain knowledge to determine direct causal relationships between variables.

- Consult with subject matter experts to validate proposed relationships.

- Review relevant literature and research findings supporting causal connections.

- Consider temporal ordering to ensure causality (causes must precede effects).

-

Document evidence supporting each proposed causal relationship.

-

Formal Model Development:

-

Create a directed acyclic graph (DAG) representing the causal structure.

- Specify structural equations for each variable based on its direct causes.

- Determine functional forms for relationships based on domain knowledge.

- Implement the model using appropriate causal modeling tools.

-

Document model assumptions and limitations clearly.

-

Model Validation:

-

Test implied conditional independencies against observational data.

- Perform sensitivity analysis to assess robustness to assumption violations.

- Compare model predictions with established findings in the domain.

- Seek expert review of model structure and assumptions.

- Iteratively refine the model based on validation results.

These methodologies integrate with standard ML workflows by informing data collection, feature engineering, model selection, and evaluation approaches. While they add complexity to the development process, they establish a solid foundation for effective fairness interventions based on causal understanding.

Implementation Challenges

When constructing causal models for bias detection, practitioners commonly face these challenges:

-

Limited Domain Knowledge: Accurate causal modeling requires substantial domain expertise, which might be incomplete or evolving. Address this by:

-

Adopting an iterative approach that evolves the causal model as knowledge improves.

- Constructing multiple candidate models representing different causal hypotheses.

- Collaborating with diverse domain experts to capture different perspectives.

-

Being explicit about uncertainty in the model and conducting sensitivity analysis.

-

Unobserved Confounders: Critical confounding variables might be unmeasured in available data. Address this by:

-

Conducting sensitivity analysis to assess how unobserved confounding might affect conclusions.

- Using domain knowledge to identify potential unmeasured confounders.

- Leveraging techniques like instrumental variables or proxy variables when appropriate.

- Explicitly documenting potential unobserved confounders and their implications for model validity.

Successfully implementing causal modeling for bias detection requires resources including domain expertise to inform model construction, data to test implied relationships, technical knowledge of causal modeling techniques, and organizational commitment to addressing bias based on causal understanding.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your causal models effectively represent bias mechanisms, implement these evaluation strategies:

-

Structural Validation:

-

Test implied conditional independencies (d-separation properties) derived from the causal graph.

- Measure the strength of associations along different causal pathways.

- Assess whether temporal sequences in data align with the proposed causal ordering.

-

Document validation evidence for key causal relationships in the model.

-

Functional Validation:

-

Evaluate whether structural equations accurately predict relationships observed in data.

- Measure goodness-of-fit for equations representing key relationships.

- Assess sensitivity of model predictions to parameter variations.

- Test whether interventions produce expected downstream effects according to the model.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated with your organization's broader fairness assessment framework, providing deeper insights than purely statistical metrics while acknowledging the limitations of causal knowledge in practical applications.

4. Case Study: Loan Approval Algorithm

Scenario Context

A financial institution is developing a machine learning algorithm to predict default risk and automate loan approval decisions. After initial testing, the data science team discovered concerning disparities: applicants from minority racial groups were being approved at significantly lower rates than white applicants with seemingly similar financial profiles.

The institution's leadership wants to understand whether these disparities represent discrimination that should be addressed or legitimate risk assessment based on relevant predictive factors. The team must determine the causal mechanisms driving these disparities to design appropriate interventions.

This scenario involves multiple stakeholders with diverse concerns: risk managers focused on accurate default prediction, compliance officers concerned about regulatory requirements, business leaders interested in expanding customer base, and applicants seeking fair access to financial resources. The fairness implications are substantial given the impact on financial inclusion and wealth-building opportunities across demographic groups.

Problem Analysis

To understand the causal mechanisms behind the observed disparities, the team constructed a causal model of the loan approval process, drawing on domain expertise, research literature, and analysis of historical lending data.

The initial causal graph revealed several potential pathways through which race might influence loan approval decisions:

- Proxy Discrimination Pathways: The model relied heavily on zip code as a predictive feature, which serves as a proxy for race due to historical residential segregation patterns. The causal graph showed no direct causal relationship between zip code and default risk when controlling for individual financial factors, suggesting this created a problematic pathway from race to loan decisions through a proxy variable.

- Indirect Discrimination Pathways: Race influences educational opportunities and employment patterns due to historical discrimination, which legitimately affect income stability and credit history, which in turn predict default risk. This represents an indirect pathway from race to loan decisions through mediators that are causally related to default risk.

- Selection Bias in Training Data: Historical lending practices created selection bias in the training data, where minority applicants who received loans represented a non-random subset of all minority applicants (typically those with exceptionally strong applications), creating biased estimates of default risk across racial groups.

The team formalized these relationships in a structural equation model that quantified how race influenced various factors in the lending process. This SEM revealed that approximately 60% of the observed approval disparity operated through proxy variables like zip code, 25% through indirect effects on legitimate predictors like credit history, and 15% through selection bias in the training data.

A correlation-based approach might have simply enforced demographic parity or removed race from the dataset, potentially approving higher-risk loans or rejecting qualified applicants. The causal approach enabled a more nuanced understanding of different bias mechanisms requiring different interventions.

From an intersectional perspective, the analysis revealed that the causal mechanisms operated differently for specific subgroups. For example, the zip code proxy effect was particularly pronounced for Black women, while selection bias in the training data most significantly affected Hispanic men, reflecting unique historical patterns of discrimination affecting these intersections differently.

Solution Implementation

Based on their causal analysis, the team implemented a structured approach to address the identified bias mechanisms:

-

Causal Variable Identification: The team systematically identified and classified variables in their lending process:

-

Protected attributes: race, gender, age

- Outcome variables: loan approval decision, interest rate

- Mediator variables: credit score, income, debt-to-income ratio, employment history

-

Confounding variables: neighborhood economic conditions, local housing markets, generational wealth

-

Causal Graph Construction: Working with domain experts in lending and fair housing, they developed a causal graph representing relationships between these variables. This graph explicitly represented both legitimate predictive pathways (e.g., income stability → default risk) and potentially problematic ones (e.g., zip code as a proxy for race).