Part 3: Model-Level Interventions (In-Processing)

Context

In-processing interventions embed fairness directly into model training, addressing bias that persists despite data-level fixes.

This Part equips you with algorithms that optimize for both accuracy and fairness simultaneously. You'll learn to reshape how models learn rather than just modifying inputs or outputs. Too many practitioners treat fairness as an afterthought rather than a core optimization criterion.

Constraint-based methods enforce fairness during training. A hiring algorithm might include constraints ensuring similar acceptance rates across demographic groups, preventing it from learning historical biases while still capturing legitimate predictive signals. These constraints reshape the solution space, guiding models toward regions where fairness and performance coexist.

Adversarial approaches leverage competing objectives to neutralize bias. By pitting a predictor against a discriminator that tries to infer protected attributes, models learn representations that preserve predictive power while becoming "blind" to sensitive features. This mirrors how GANs work, but with fairness as the goal.

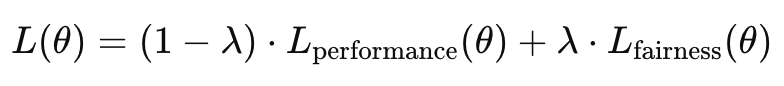

These interventions transform how you build models—from loss function formulation through hyperparameter selection to evaluation strategies. Techniques range from simple regularization terms to sophisticated multi-objective optimization frameworks that navigate fairness-performance trade-offs.

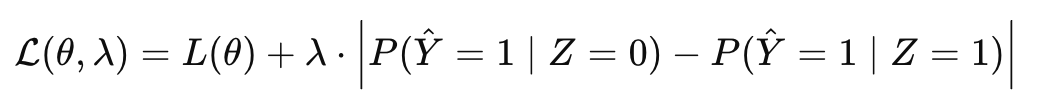

The In-Processing Fairness Toolkit you'll develop in Unit 5 represents the third component of the Fairness Intervention Playbook. This tool will help you select and implement appropriate algorithmic interventions for different model architectures, ensuring fairness becomes intrinsic to how your models learn.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this Part, you will be able to:

- Implement fairness constraints within model optimization objectives. You will formulate mathematical constraints that enforce group fairness criteria during training, enabling models that natively satisfy fairness definitions rather than requiring post-hoc corrections.

- Design adversarial debiasing approaches for neural networks. You will create model architectures where adversarial components remove protected information from learned representations, preventing discrimination while preserving useful predictive patterns.

- Apply regularization techniques that promote fair learning. You will integrate fairness-specific regularization terms into objective functions, guiding models away from discriminatory solutions through penalization rather than hard constraints.

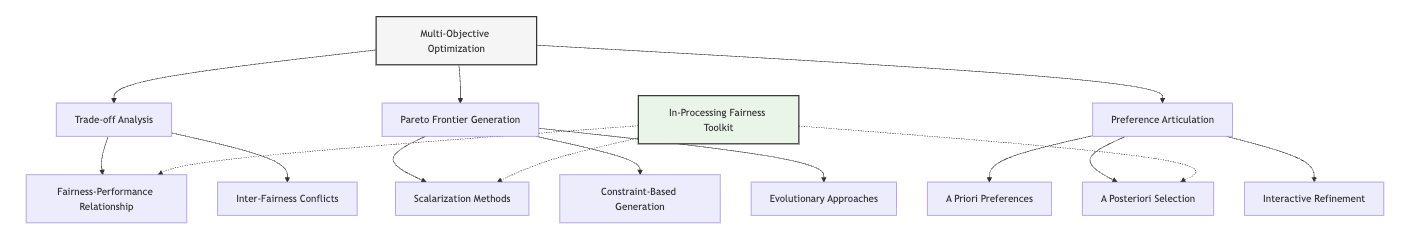

- Develop multi-objective optimization strategies for balancing fairness and performance. You will implement training procedures that navigate the Pareto frontier between competing objectives, creating models that achieve optimal trade-offs rather than sacrificing either fairness or accuracy.

- Adapt in-processing techniques to different model architectures. You will modify fairness interventions to work across diverse model types from linear classifiers to deep networks, ensuring fairness remains achievable regardless of your modeling approach.

Units

Unit 1

Unit 1: Fairness Objectives and Constraints

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How can abstract fairness definitions be translated into concrete optimization objectives and constraints that algorithms can directly optimize during training?

- Question 2: What are the mathematical and computational implications of incorporating fairness constraints into model optimization, and how do these affect model performance?

Conceptual Context

When developing machine learning models that make consequential decisions, fairness cannot be an afterthought. While pre-processing approaches modify training data before model development, in-processing techniques directly integrate fairness into the learning algorithm itself. This integration creates models that are inherently fair by design rather than attempting to correct unfairness after training.

Constraints and objectives form the mathematical core of machine learning optimization. Standard algorithms typically optimize a single objective (such as accuracy or log-likelihood) without explicit fairness considerations. By reformulating these optimization problems to include fairness definitions as explicit constraints or additional objectives, you can develop models that balance traditional performance metrics with fairness requirements during the training process itself.

This approach is particularly valuable because it addresses fairness directly in the model's decision boundary rather than through indirect data modifications. As Dwork et al. (2012) noted, "Solutions that rely exclusively on data pre-processing cannot guarantee fair decisions if the underlying algorithm can still construct biased decision boundaries." In contrast, in-processing approaches provide mathematical guarantees about the fairness properties of the resulting model.

This Unit establishes the foundation for all subsequent in-processing techniques by showing how fairness definitions can be translated into the language of mathematical optimization. You'll learn how to formulate constrained optimization problems that enforce fairness requirements while maintaining predictive performance. This understanding will directly inform the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit you'll develop in Unit 5, enabling you to select and implement appropriate in-processing techniques for specific fairness challenges.

2. Key Concepts

Translating Fairness Definitions to Mathematical Constraints

Fairness definitions provide conceptual criteria for equitable treatment, but to incorporate them into model training, you must translate these definitions into precise mathematical formulations that algorithms can optimize. This translation process is fundamental for in-processing techniques because it transforms abstract fairness goals into concrete computational objectives.

Different fairness definitions require different mathematical formulations. For example, demographic parity can be expressed as equality constraints on prediction rates across groups, while equalized odds requires conditional constraints that consider both predictions and ground truth labels.

This concept intersects with optimization theory by extending standard machine learning objectives to incorporate fairness. It connects to algorithmic implementation by requiring modifications to training procedures that can handle these additional constraints.

Zafar et al. (2017) pioneered this approach by showing how fairness constraints could be incorporated into logistic regression through convex relaxations. For demographic parity, they formulated a constraint that equalizes the mean prediction across protected groups:

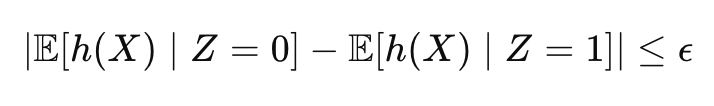

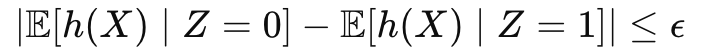

Where h(X) is the model's prediction, Z is the protected attribute, and ε is a small tolerance. This constraint ensures that the average prediction for different groups differs by no more than ε, directly enforcing the demographic parity criterion during training.

For the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit you'll develop, understanding these translations is essential for implementing fairness constraints across different model types and fairness definitions. This knowledge enables you to select appropriate constraint formulations for specific fairness requirements and model architectures.

Constrained Optimization Approaches

Once fairness definitions are translated into mathematical constraints, you must integrate these constraints into the learning process through constrained optimization techniques. This integration is essential for in-processing because it determines how the algorithm will navigate the trade-off between its original objective and the fairness constraints.

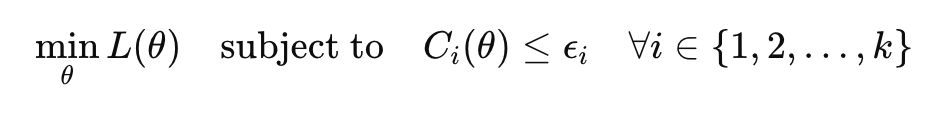

Standard machine learning models typically minimize an unconstrained loss function: min₍θ₎ L(θ)

Where L(θ) represents the loss function (e.g., cross-entropy loss) and θ represents the model parameters. To incorporate fairness, this problem is reformulated with constraints:

Where Cᵢ(θ) represents fairness constraint functions and εᵢ represents tolerance levels for each constraint.

This concept interacts with fairness definitions by determining how strictly different fairness criteria will be enforced. It connects to practical implementation by influencing both algorithm selection and computational requirements, as constrained optimization is generally more complex than unconstrained approaches.

Agarwal et al. (2018) demonstrated how constrained optimization for fairness could be implemented through a reduction approach that converts constrained problems into a sequence of unconstrained ones. Their method enables the application of fairness constraints to any model class with standard training procedures, making constrained fairness more broadly applicable.

For the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit, understanding these optimization approaches is crucial for implementing fairness constraints across different model architectures. This knowledge helps you select appropriate algorithms based on the mathematical properties of your constraints and the computational resources available for training.

Lagrangian Methods and Duality

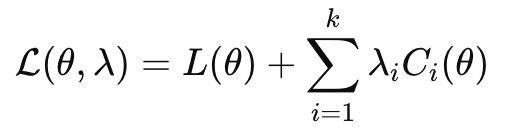

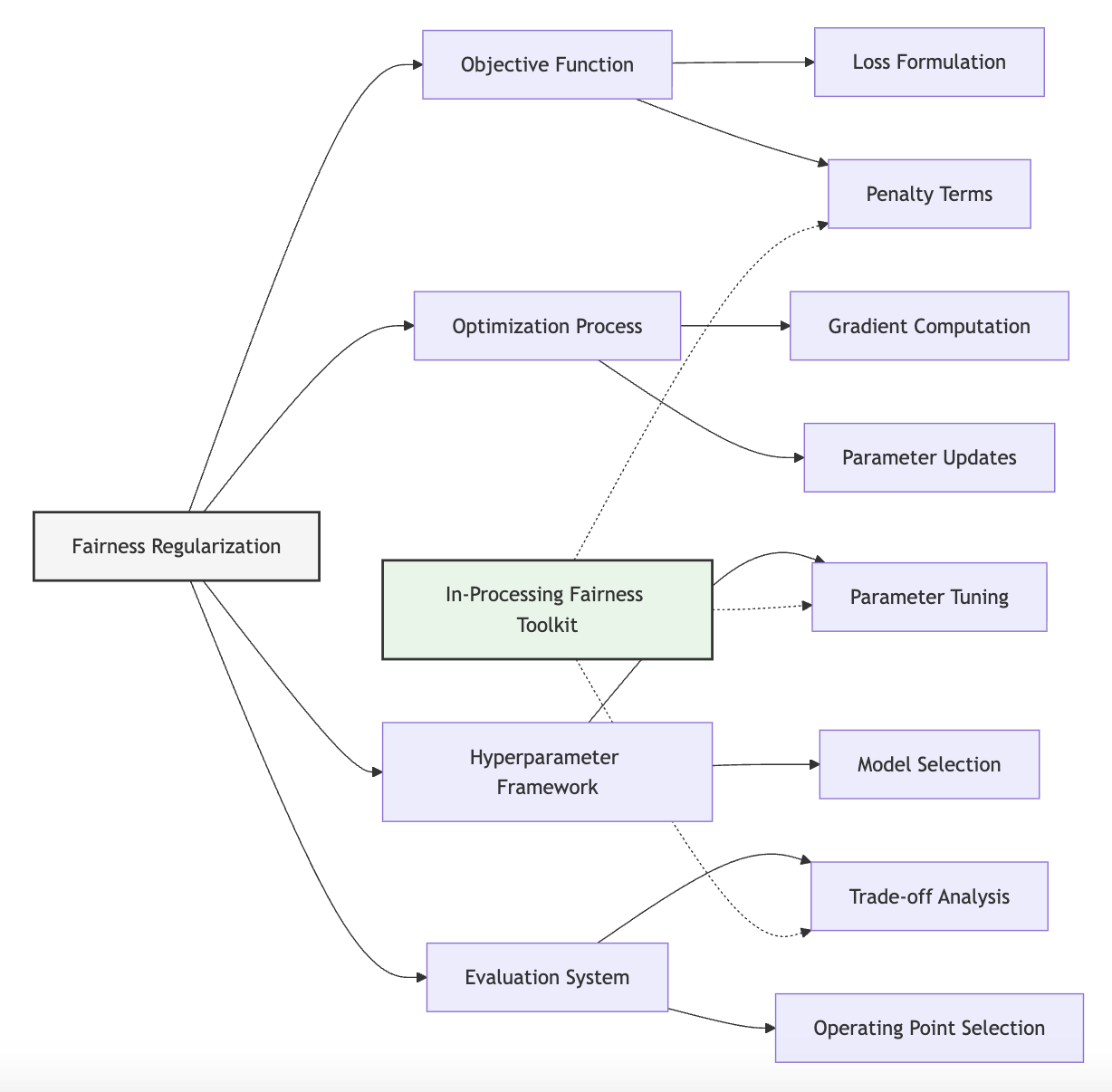

Lagrangian methods provide a powerful framework for solving constrained optimization problems by incorporating constraints into the objective function through Lagrange multipliers. This approach is particularly valuable for fairness because it transforms hard constraints into soft penalties that can be more easily optimized.

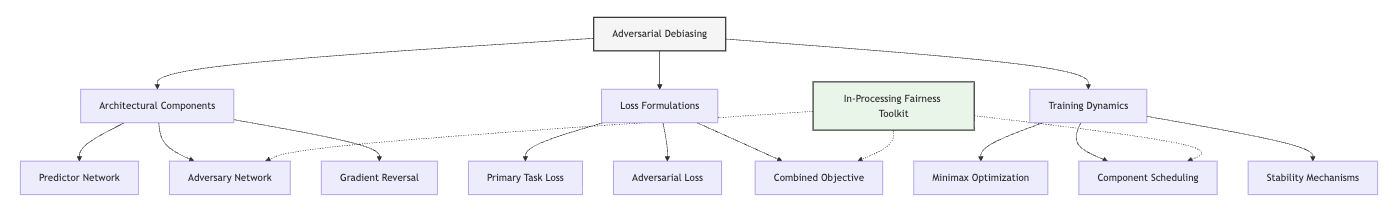

The Lagrangian formulation of a constrained fairness problem takes the form:

Where λᵢ are Lagrange multipliers that control the importance of each constraint. This formulation allows algorithms to balance the original objective against fairness requirements through appropriate tuning of the multipliers.

This concept connects to constraint enforcement by determining how strictly fairness requirements are maintained. It relates to regularization approaches by showing how constraints can be reformulated as penalties in the objective function.

Cotter et al. (2019) extended Lagrangian methods for fairness by developing a proxy-Lagrangian formulation that handles non-differentiable constraints more effectively. Their approach enables training with multiple fairness constraints simultaneously, allowing for more comprehensive fairness guarantees.

For the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit, understanding Lagrangian methods is essential for implementing fairness constraints in ways that balance enforcement with optimization stability. This knowledge enables you to transform strict fairness constraints into more flexible formulations that can be optimized efficiently while still providing strong fairness guarantees.

Feasibility and Trade-offs

Incorporating fairness constraints into optimization creates fundamental trade-offs between competing objectives and raises important questions about constraint feasibility. Understanding these trade-offs is critical because it determines what combinations of fairness and performance are achievable in practice.

The feasible region for a constrained optimization problem is the set of all parameter values that satisfy all constraints. When fairness constraints are too strict or conflict with the data structure, this region may be very small or even empty, making the problem infeasible. Even when feasible solutions exist, fairness constraints typically reduce the model's performance on traditional metrics.

This concept intersects with impossibility theorems by illustrating the practical implications of mathematical limitations. It connects to implementation decisions by influencing how strictly fairness constraints should be enforced in different contexts.

Menon and Williamson (2018) analyzed these trade-offs mathematically, showing how different fairness constraints affect the achievable accuracy. Their work provides theoretical bounds on performance losses when enforcing fairness constraints, helping practitioners understand the costs of different fairness requirements.

For the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit, understanding these trade-offs is essential for setting appropriate fairness constraints and communicating their implications to stakeholders. This knowledge enables you to navigate the fairness-performance frontier effectively, finding solutions that provide meaningful fairness guarantees while maintaining acceptable performance for your application.

Domain Modeling Perspective

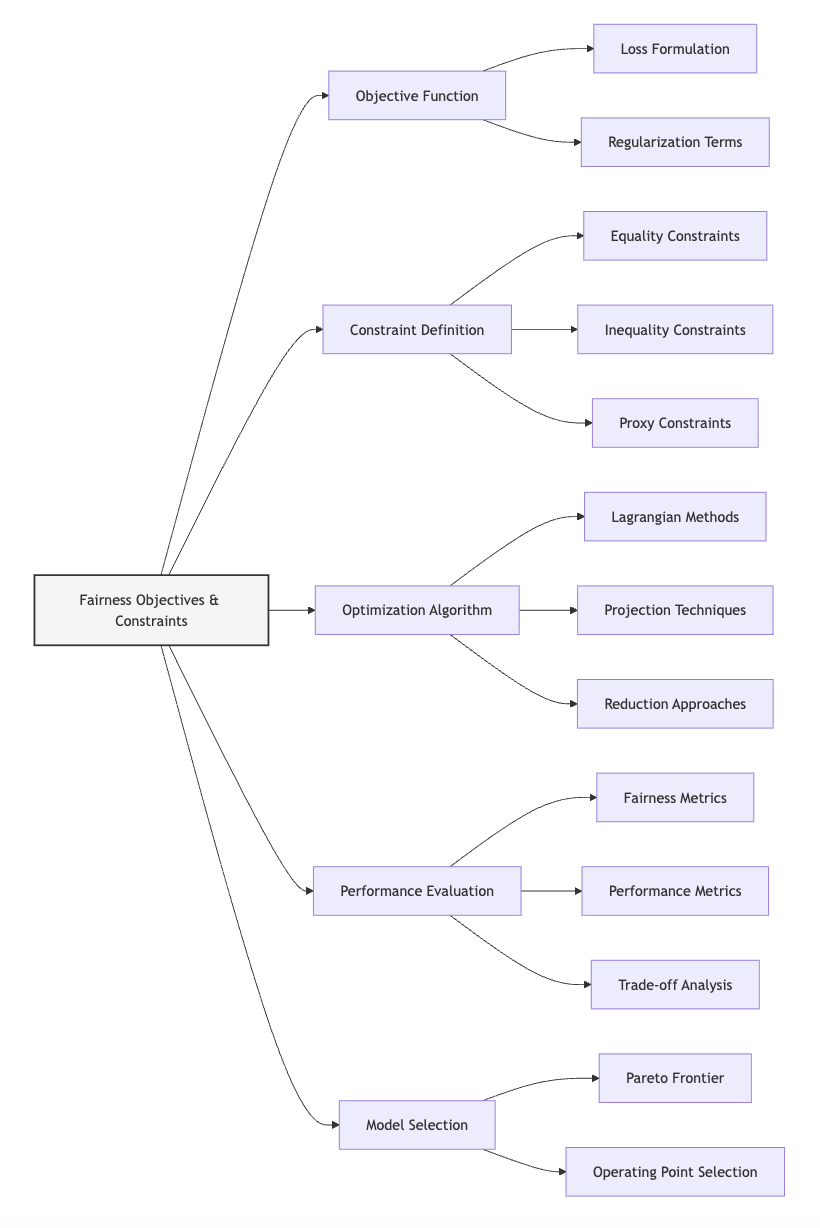

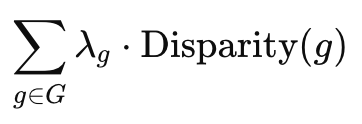

From a domain modeling perspective, fairness objectives and constraints map to specific components of ML systems:

- Objective Function: Fairness considerations can be incorporated as additional terms in what the model optimizes.

- Constraint Definition: Fairness criteria can be enforced as boundaries on acceptable model behavior.

- Optimization Algorithm: The solution approach must be adapted to handle fairness constraints efficiently.

- Performance Evaluation: Both traditional metrics and fairness criteria must be considered when assessing models.

- Model Selection: Trade-offs between fairness and performance influence which model is ultimately deployed.

This domain mapping helps you understand how fairness constraints affect different aspects of model development rather than viewing them as isolated modifications. The In-Processing Fairness Toolkit will leverage this mapping to guide appropriate constraint implementations based on which components can be modified in your specific context.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract optimization concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Translating fairness definitions to constraints is similar to converting building codes into architectural specifications. Just as architects must translate requirements like "accessible to wheelchair users" into concrete measurements (door widths, ramp angles), machine learning engineers must translate fairness definitions like "demographic parity" into precise mathematical expressions that constrain the model's behavior. Both translations convert abstract principles into specific, measurable criteria that can be verified and enforced during construction/training.

- Constrained optimization for fairness resembles navigating with route restrictions in GPS navigation. A standard navigation system might simply minimize travel time (like a model minimizing error), but adding constraints such as "avoid highways" or "avoid toll roads" is similar to adding fairness constraints. These constraints may lead to a longer route (reduced model performance) but ensure the journey satisfies important requirements. Just as the navigation system must find the fastest route that respects all restrictions, constrained optimization finds the best-performing model that satisfies all fairness constraints.

- The feasibility-performance trade-off in fairness is analogous to budgeting with multiple financial goals. Imagine trying to simultaneously save for retirement, a home down payment, and an emergency fund with a limited income. Allocating more to one goal necessarily reduces what's available for others. Similarly, enforcing stricter fairness constraints typically reduces resources available for optimizing performance. In both cases, you must decide which goals are non-negotiable (hard constraints) versus aspirational (soft constraints) and find a balance that best satisfies your priorities given the resources available.

Intersectionality Consideration

Traditional fairness constraints often address protected attributes independently, potentially missing unique fairness concerns at intersections of multiple identities. As demonstrated by Kearns et al. (2018) in their work on subgroup fairness, models that satisfy fairness constraints for individual protected attributes may still discriminate against specific intersectional subgroups.

For example, a lending algorithm might achieve demographic parity across both gender and race categories independently, while still discriminating against specific intersections like women of a particular racial background. Standard constraint formulations would miss these intersectional disparities.

Implementing intersectional fairness through constraints requires:

- Multi-attribute constraint formulations that consider all relevant demographic combinations.

- Rich constraint specifications that can express complex fairness requirements across overlapping groups.

- Computational approaches that handle the exponential growth in constraints as the number of protected attributes increases.

Foulds et al. (2020) addressed this challenge by developing an intersectional fairness framework that efficiently enforces fairness across exponentially many subgroups through statistical aggregation. Their approach provides stronger guarantees for intersectional fairness while maintaining computational tractability.

For the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit, addressing intersectionality requires constraint formulations that explicitly consider interactions between protected attributes. This might involve:

- Separate constraints for important intersectional subgroups.

- Hierarchical constraint structures that enforce fairness at multiple levels of granularity.

- Statistical techniques that efficiently handle the combinatorial explosion of subgroups.

By incorporating these intersectional considerations, the framework will ensure that fairness constraints protect all demographic subgroups, not just those defined by single attributes.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To effectively translate fairness definitions into practical optimization constraints, follow this structured methodology:

-

Constraint Formulation:

-

Select appropriate mathematical expressions based on your fairness definition (demographic parity, equalized odds, etc.).

- Determine whether to use equality constraints (C(θ) = 0) or inequality constraints (C(θ) ≤ ε).

- Consider proxy constraints that approximate complex fairness criteria with more tractable expressions.

-

Document the mathematical formulation and its relationship to the original fairness definition.

-

Optimization Integration:

-

Select an appropriate constrained optimization algorithm based on constraint properties (convexity, differentiability, etc.).

- Implement Lagrangian formulations that incorporate constraints into the objective function.

- Develop efficient projection techniques for maintaining constraint feasibility during training.

-

Establish monitoring approaches for tracking constraint satisfaction throughout optimization.

-

Feasibility Analysis:

-

Verify that fairness constraints can be satisfied given the data distribution.

- Identify potential conflicts between multiple fairness constraints.

- Determine appropriate tolerance levels (ε) that balance strict fairness with achievable solutions.

- Document feasibility findings to inform constraint adjustments if necessary.

These methodologies integrate with standard ML workflows by extending existing optimization procedures to handle fairness constraints. While they add complexity to model training, they enable direct enforcement of fairness properties that may be difficult to achieve through pre-processing alone.

Implementation Challenges

When implementing fairness constraints, practitioners commonly face these challenges:

-

Optimization Difficulties: Fairness constraints can create non-convex optimization landscapes that are harder to navigate. Address this by:

-

Starting with simpler constraint formulations and gradually increasing complexity.

- Using advanced optimization techniques like alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM).

- Implementing warm-start approaches that begin from unconstrained solutions.

-

Monitoring convergence behavior and adjusting optimization parameters accordingly.

-

Constraint-Performance Trade-offs: Strict fairness constraints often reduce model performance on standard metrics. Address this by:

-

Analyzing the Pareto frontier to understand available trade-offs.

- Implementing adjustable constraint formulations that can be tuned based on application requirements.

- Developing multiple models with different constraint settings to provide options for stakeholders.

- Creating clear visualizations that communicate trade-offs to non-technical decision-makers.

Successfully implementing fairness constraints requires computational resources for more complex optimization, expertise in mathematical programming and fairness definitions, and organizational willingness to potentially sacrifice some performance for improved fairness. The specific technical requirements will vary based on the model type and fairness criteria being enforced.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your fairness constraints are working effectively, implement these evaluation strategies:

-

Constraint Satisfaction Verification:

-

Calculate constraint violations on both training and validation data.

- Monitor constraint satisfaction throughout training to identify potential instabilities.

- Verify that constraints remain satisfied when the model is applied to new data.

-

Document constraint violations and their magnitudes to inform potential adjustments.

-

Performance Impact Assessment:

-

Quantify performance differences between constrained and unconstrained models.

- Analyze which performance metrics are most affected by fairness constraints.

- Determine whether performance impacts are acceptable given application requirements.

- Identify specific subgroups or data regions where performance changes are most significant.

These evaluation approaches should be integrated with your organization's broader model assessment framework, providing a comprehensive understanding of both fairness properties and traditional performance metrics.

4. Case Study: Loan Approval System

Scenario Context

A financial institution is developing a machine learning model to predict default risk for loan applications. The model will be used to automate preliminary approval decisions, with higher-risk applications receiving additional manual review. The dataset includes financial history, current income and assets, loan amounts, and repayment history for past customers. Protected attributes like gender, age, and race are available for fairness analysis but should not directly influence decisions.

Initial unconstrained models showed concerning disparities: the approval rate for applicants from minority racial groups was 15% lower than for the majority group, even when controlling for relevant financial factors. The data science team must address this disparity while maintaining the model's ability to accurately predict default risk.

Key stakeholders include the bank's risk management team concerned with financial performance, compliance officers responsible for ensuring regulatory adherence, customers from diverse backgrounds seeking fair evaluation, and executives balancing business goals with ethical considerations. The fairness implications are significant given the potential impact on financial access and opportunity.

Problem Analysis

Applying the concepts from this Unit to the loan approval scenario:

- Fairness Definition Translation: The team decided to enforce demographic parity for preliminary approvals, requiring similar approval rates across demographic groups. This definition translates to a constraint on the difference in mean predictions between protected groups:

Where h(X) is the model's prediction (approval probability), Z is the protected attribute, and ε is a small tolerance that allows for minor disparities due to legitimate differences in qualification.

- Constraint Implementation: The team initially attempted to implement strict equality constraints (ε = 0), but found this infeasible given the genuine correlations between default risk factors and protected attributes in their historical data. They then explored inequality constraints with varying tolerance levels, finding that ε = 0.05 (allowing up to 5% difference in approval rates) provided a reasonable balance between fairness and feasibility.

- Optimization Approach: For their logistic regression model, they implemented the constraint using a Lagrangian formulation:

This formulation allowed them to adjust the Lagrange multiplier (λ) to control the trade-off between prediction accuracy and fairness.

- Intersectional Considerations: Initial implementations focused only on racial disparities, but further analysis revealed unique challenges for specific intersectional groups, particularly young applicants from minority backgrounds with limited credit history. To address this, they extended their constraint formulation to include key intersectional categories, ensuring fairness across both individual attributes and their important combinations.

From a feasibility perspective, the team discovered that strict demographic parity (ε = 0) would reduce the model's default prediction accuracy by approximately 8%, while the relaxed constraint (ε = 0.05) reduced accuracy by only 3%. This analysis helped stakeholders understand the concrete trade-offs involved in different fairness requirements.

Solution Implementation

To address the fairness challenges through constrained optimization, the team implemented a comprehensive approach:

-

For Constraint Formulation, they:

-

Developed mathematical expressions for demographic parity that could be efficiently computed during training.

- Created relaxed inequality constraints with adjustable tolerance parameters.

- Extended the constraints to address key intersectional categories identified during data analysis.

-

Documented the relationship between their mathematical constraints and the fairness requirements.

-

For Optimization Integration, they:

-

Implemented a projected gradient approach for their logistic regression model.

- Developed Lagrangian formulations that incorporated fairness constraints into the objective function.

- Created an ADMM implementation for handling multiple constraints simultaneously.

-

Established monitoring procedures to track constraint satisfaction during training.

-

For Feasibility Analysis, they:

-

Analyzed the Pareto frontier to understand available trade-offs between fairness and default prediction.

- Developed multiple models with different constraint settings (ε values ranging from 0.01 to 0.10).

- Created visualizations showing both performance metrics and fairness properties for different constraint configurations.

- Documented the achievable combinations of fairness and performance to inform stakeholder decisions.

Throughout implementation, they maintained explicit focus on intersectional effects, ensuring that fairness constraints protected all demographic subgroups rather than just addressing aggregate disparities.

Outcomes and Lessons

The constrained optimization approach yielded several key results:

- The final model with ε = 0.05 reduced the approval rate disparity from 15% to 4.8%, while limiting the decrease in overall default prediction accuracy to 3%.

- The intersectional constraints successfully addressed unique challenges for young minority applicants, reducing previously undetected disparities in this subgroup.

- The constraint formulation provided mathematical guarantees about maximum fairness disparities, creating more transparent and defensible model properties compared to ad hoc adjustments.

The team faced several challenges during implementation, including optimization difficulties with multiple constraints and communication challenges when explaining trade-offs to stakeholders. They found that visualizing the Pareto frontier of fairness-performance combinations was particularly effective for facilitating informed decisions about constraint settings.

Key generalizable lessons included:

- The importance of relaxed constraints with appropriate tolerance levels rather than strict equality constraints, which are often infeasible in real-world scenarios.

- The value of training multiple models with different constraint settings to understand available trade-offs rather than committing to a single fairness-performance balance prematurely.

- The necessity of explicitly addressing intersectional fairness through additional constraints rather than assuming protection of individual attributes will extend to their intersections.

These insights directly inform the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit in Unit 5, demonstrating how theoretical constraint formulations translate into practical fairness improvements in high-stakes applications.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Mathematical Formulation Choices

Q: How do I choose between equality constraints, inequality constraints, and Lagrangian formulations when implementing fairness in my model?

A: The choice depends on your fairness requirements, optimization capabilities, and application context. Equality constraints (C(θ) = 0) provide the strongest fairness guarantees by requiring exact satisfaction of fairness criteria, but they're often infeasible or lead to significant performance degradation in real-world scenarios with underlying data disparities. Inequality constraints (C(θ) ≤ ε) offer more flexibility by allowing small fairness violations up to a tolerance threshold, making them more practical while still providing meaningful guarantees. Lagrangian formulations transform constraints into penalty terms in the objective function, offering the most flexibility by allowing you to control the fairness-performance trade-off through multiplier tuning.

Generally, start with Lagrangian formulations during exploratory analysis to understand potential trade-offs. If you need formal guarantees, transition to inequality constraints with appropriate tolerance levels based on your exploration. Reserve equality constraints for scenarios where perfect fairness is absolutely required and feasibility analysis confirms they can be satisfied. Your choice should also consider computational factors: equality constraints often create harder optimization problems, while Lagrangian approaches can work with standard optimization algorithms. Finally, consider regulatory requirements—some contexts may legally require specific levels of fairness that necessitate formal constraints rather than penalty approaches.

FAQ 2: Handling Multiple Protected Attributes

Q: How should I formulate constraints when dealing with multiple protected attributes (gender, race, age, etc.) simultaneously?

A: Managing multiple protected attributes requires careful constraint design to avoid an explosion of constraints while still ensuring comprehensive fairness. Consider these strategies: First, implement separate constraints for each individual protected attribute, which provides basic protection across all attributes but may miss intersectional effects. Second, add specific constraints for important intersectional categories identified during data analysis, focusing on combinations with sufficient data for reliable estimation. Third, consider hierarchical approaches that enforce overall fairness while adding specific protections for vulnerable subgroups.

From a computational perspective, be aware that naively adding constraints for all possible attribute combinations leads to an exponential increase in constraints, creating optimization difficulties. Instead, try statistical approaches like the one proposed by Kearns et al. (2018) that enforce fairness across all subgroups without explicitly enumerating them, or aggregate approaches that combine multiple constraint violations into a single term. When implementing, monitor both individual constraints and overall system behavior to ensure that optimizing for one constraint doesn't adversely affect others. Finally, document your constraint design decisions, explaining which attribute combinations received explicit constraints versus those covered by more general protections, creating transparency about your fairness approach for stakeholders.

6. Project Component Development

Component Description

In Unit 5, you will develop the constraint formulation section of the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit. This component will provide a systematic methodology for translating fairness definitions into concrete mathematical constraints and integrating these constraints into optimization algorithms.

Your deliverable will include mathematical formulations for different fairness definitions, implementation patterns for incorporating these constraints into various model types, and decision frameworks for navigating constraint-related trade-offs.

Development Steps

- Create a Fairness Constraint Catalog: Develop a comprehensive collection of mathematical constraints corresponding to different fairness definitions (demographic parity, equalized odds, etc.). For each constraint, provide the formal mathematical expression, its relationship to the original fairness definition, and implementation considerations.

- Design Implementation Patterns: Create practical code patterns for incorporating fairness constraints into different model types and optimization algorithms. Include Lagrangian formulations, projection approaches, and specialized algorithms for constrained optimization.

- Develop Trade-off Analysis Tools: Build frameworks for analyzing the feasibility of constraint combinations and evaluating the performance impact of different constraint configurations. Create approaches for generating and visualizing the Pareto frontier of fairness-performance trade-offs.

Integration Approach

This constraint formulation component will interface with other parts of the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit by:

- Building on the causal understanding from Part 1 to determine which fairness definitions (and thus constraints) are most appropriate for specific discrimination mechanisms.

- Complementing the pre-processing approaches from Part 2 by identifying when constraints are needed to address fairness issues that data modifications cannot resolve.

- Providing the mathematical foundation for the adversarial approaches in Unit 2 and regularization methods in Unit 3, showing how different in-processing techniques relate to constrained optimization.

To enable successful integration, use consistent mathematical notation across components, establish clear relationships between constraints and other techniques, and provide guidance on combining constraint approaches with other interventions when appropriate.

7. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

In this Unit, you've explored how fairness definitions can be translated into mathematical constraints and incorporated directly into model optimization. Key insights include:

- Mathematical Translation of fairness definitions provides precise expressions that algorithms can optimize, transforming abstract fairness goals into concrete computational objectives.

- Constrained Optimization approaches integrate fairness requirements directly into the learning process, creating models with inherent fairness properties rather than relying on post hoc corrections.

- Lagrangian Methods offer a flexible framework for incorporating fairness constraints into objective functions through multipliers that balance competing goals.

- Feasibility Analysis helps identify what combinations of fairness and performance are achievable, informing appropriate constraint formulations and tolerance levels.

These concepts directly address our guiding questions by showing how fairness definitions can be translated into mathematical constraints and how these constraints affect model optimization and performance. This knowledge provides the foundation for implementing in-processing fairness techniques that create inherently fair models.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Start by clearly defining which fairness criteria are most important for your application based on ethical, legal, and business requirements.

- Translate these definitions into mathematical constraints, considering both equality and inequality formulations with appropriate tolerance levels.

- Implement constrained optimization using techniques appropriate for your model architecture, such as Lagrangian methods or specialized constrained optimizers.

- Analyze trade-offs between fairness and performance by training multiple models with different constraint configurations.

- Document your constraint formulations and their relationship to fairness definitions, creating transparency about your fairness approach.

If you're new to constrained optimization, begin with simpler inequality constraints with adjustable tolerance levels before attempting more complex formulations. Remember that feasibility is crucial—constraints that cannot be satisfied will lead to optimization failures, so verify that your constraints are achievable given your data distribution.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will build on this foundation by exploring adversarial debiasing approaches. While constraint-based methods directly modify the optimization problem, adversarial techniques use competing neural networks to prevent models from learning discriminatory patterns. You'll learn how to design adversarial architectures that implement similar fairness goals through a different mechanism, providing an alternative approach when explicit constraints are difficult to formulate or optimize.

The constraint formulations you've learned here will provide important context for understanding these adversarial methods, as both approaches ultimately seek to enforce fairness properties during training. By understanding both constraint-based and adversarial techniques, you'll develop a more comprehensive toolkit for in-processing fairness interventions that can be applied across different model architectures and fairness requirements.

References

Agarwal, A., Beygelzimer, A., Dudík, M., Langford, J., & Wallach, H. (2018). A reductions approach to fair classification. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 60-69). PMLR.

Cotter, A., Jiang, H., Gupta, M. R., Wang, S., Narayan, T., You, S., & Sridharan, K. (2019). Optimization with non-differentiable constraints with applications to fairness, recall, churn, and other goals. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 20(172), 1-59.

Dwork, C., Hardt, M., Pitassi, T., Reingold, O., & Zemel, R. (2012). Fairness through awareness. In Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (pp. 214-226).

Foulds, J. R., Islam, R., Keya, K. N., & Pan, S. (2020). An intersectional definition of fairness. In IEEE 36th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE) (pp. 1918-1921).

Kearns, M., Neel, S., Roth, A., & Wu, Z. S. (2018). Preventing fairness gerrymandering: Auditing and learning for subgroup fairness. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 2564-2572).

Menon, A. K., & Williamson, R. C. (2018). The cost of fairness in binary classification. In Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency (pp. 107-118).

Zafar, M. B., Valera, I., Gomez Rodriguez, M., & Gummadi, K. P. (2017). Fairness constraints: Mechanisms for fair classification. In Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (pp. 962-970). PMLR.

Unit 2

Unit 2: Adversarial Debiasing Approaches

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions

- Question 1: How can we leverage adversarial learning techniques to prevent models from encoding discriminatory patterns while preserving their predictive performance?

- Question 2: What architectural and optimization principles enable effective implementation of adversarial debiasing across different model types and fairness definitions?

Conceptual Context

Adversarial debiasing represents a powerful paradigm for embedding fairness directly into model training. While constraint-based approaches from Unit 1 explicitly restrict the optimization space, adversarial methods take a fundamentally different approach—they create a competitive learning environment where one component attempts to predict the target variable while another component tries to prevent protected attributes from being encoded in the model's representations or outputs.

This adversarial framework is particularly valuable when working with complex models like neural networks, where explicit constraints may be difficult to formulate or enforce. By training the predictor to be simultaneously accurate on the primary task and resistant to protected attribute inference, adversarial debiasing achieves a form of "information filtering" that enables fairness without requiring explicit modification of the training data or post-processing of model outputs.

The significance of adversarial approaches extends beyond their technical elegance. When fairness cannot be achieved through simple data transformations or constraint-based methods, adversarial techniques offer a powerful alternative that maintains model expressivity while reducing discriminatory behavior. As you'll discover, these approaches function by actively unlearning problematic correlations between protected attributes and outcomes, rather than simply restricting model behavior through hard constraints.

This Unit builds directly on the optimization foundations established in Unit 1 by introducing the adversarial framework as an alternative mechanism for implementing similar fairness goals. The adversarial techniques you'll explore here will complement the regularization approaches of Unit 3 and the multi-objective methods of Unit 4, forming a critical component of the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit you'll develop in Unit 5.

2. Key Concepts

Adversarial Network Architecture for Fairness

Adversarial debiasing employs a network architecture with competing components designed to achieve fairness through a form of "representational protection." This concept is essential for fairness because it enables models to learn representations that are simultaneously predictive of the target variable and independent of protected attributes, effectively preventing problematic patterns from being encoded within the model.

The core architectural paradigm, inspired by Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), involves two primary components:

- A predictor that attempts to accurately predict the target variable Y from input features X

- An adversary that attempts to predict the protected attribute A from either the predictor's output or internal representations

These components are trained with opposing objectives: the predictor aims to maximize prediction accuracy while minimizing the adversary's ability to infer protected attributes. This creates a minimax game where the equilibrium solution represents a model that achieves high accuracy while ensuring protected attributes cannot be recovered from its predictions or representations.

Zhang et al. (2018) formalized this approach in their seminal paper "Mitigating Unwanted Biases with Adversarial Learning," demonstrating how adversarial techniques could implement various fairness definitions. Their research showed that by carefully designing the adversarial objective, models could achieve demographic parity, equalized odds, or equal opportunity while maintaining competitive predictive performance.

The architectural design has significant implications for both fairness and implementation. As Beutel et al. (2017) demonstrated, different architectural choices—such as whether the adversary operates on the model's internal representations or final outputs—lead to different fairness properties and training dynamics. These choices must be aligned with specific fairness definitions and application requirements.

For the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit you'll develop in Unit 5, understanding these architectural patterns is crucial for determining when and how to implement adversarial approaches across different model types and fairness definitions.

Fairness Through Adversarial Unlearning

Adversarial debiasing achieves fairness through a process that can be conceptualized as "adversarial unlearning"—actively removing information about protected attributes from model representations while preserving predictive power. This mechanism is fundamentally different from constraint-based approaches and offers unique capabilities for balancing fairness and performance.

This concept connects to representational fairness, which focuses on what information is encoded within a model's internal states rather than just its outputs. By preventing the model from encoding protected attributes in its representations, adversarial methods address a deeper form of fairness than approaches that merely constrain output distributions.

As demonstrated by Edwards and Storkey (2016) in their work on fair representations, adversarial training can create "censored representations" that are simultaneously informative for the prediction task and uninformative about protected attributes. Their research showed that this approach could effectively remove protected attribute information from intermediate representations while maintaining high performance on the primary task.

The key insight is that adversarial unlearning operates by creating a form of information bottleneck that filters out protected attribute information. This filtering happens dynamically during training, as the predictor learns to encode features in ways that the adversary cannot exploit to infer protected attributes.

One significant advantage of this approach is its flexibility across different model architectures. While constraint-based methods often require specific mathematical formulations tied to model types, adversarial unlearning can be applied to virtually any differentiable model, from simple linear classifiers to complex neural networks.

For your In-Processing Fairness Toolkit, understanding this unlearning mechanism will help you determine when adversarial approaches offer advantages over other fairness techniques, particularly for complex models where protected attribute information might be encoded in subtle, non-linear ways.

Optimization Dynamics and Training Stability

Implementing adversarial debiasing requires careful attention to optimization dynamics and training stability. While conceptually elegant, adversarial training introduces significant challenges due to the competing objectives and potential for unstable dynamics during the learning process.

This concept is critical for practical implementation because naive adversarial training often suffers from instability issues, including oscillating behavior, mode collapse, or failure to converge to meaningful solutions. Understanding and addressing these challenges is essential for developing effective fairness interventions.

Research by Louppe et al. (2017) on adversarial learning demonstrates that the minimax game between predictor and adversary creates a fundamentally different optimization landscape than standard supervised learning. Their work reveals that the saddle-point nature of the objective function requires specialized training procedures to ensure stable convergence to desirable solutions.

Key optimization considerations include:

- Balancing component strength: If the adversary becomes too powerful too quickly, the predictor may struggle to learn useful representations; conversely, if the adversary is too weak, fairness objectives may not be enforced.

- Gradient reversal: Implemented through a special layer that multiplies gradients by a negative constant during backpropagation, effectively allowing the predictor to minimize the primary loss while maximizing the adversary's loss.

- Progressive training schedules: Gradually increasing the weight of the adversarial component during training, allowing the predictor to first learn useful representations before enforcing fairness constraints.

- Regularized adversarial objectives: Adding regularization terms to the adversarial objective to promote stability and prevent pathological solutions.

Research by Madras et al. (2018) demonstrated that implementing these techniques correctly is essential for achieving both fairness and performance goals. Their empirical studies showed that without proper optimization strategies, adversarial methods could lead to models that are either unfair or perform poorly on the primary task.

For the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit, understanding these optimization dynamics will enable you to provide practical guidance on implementing stable and effective adversarial training across different fairness definitions and model architectures.

Domain Modeling Perspective

From a domain modeling perspective, adversarial debiasing maps to specific components of ML systems:

- Model Architecture: Adversarial debiasing requires specific architectural designs with competing components and information flow patterns.

- Loss Function Design: The approach employs complex loss functions that balance primary task performance against protected attribute predictability.

- Representation Learning: Adversarial mechanisms specifically target how information is encoded in model representations.

- Optimization Process: The competing objectives create unique training dynamics requiring specialized optimization approaches.

- Fairness Evaluation: Measuring both task performance and protected attribute leakage becomes essential for assessing effectiveness.

This domain mapping helps you understand how adversarial techniques influence different aspects of model development rather than viewing them as isolated modifications. The In-Processing Fairness Toolkit will leverage this mapping to guide appropriate technique selection and implementation across different modeling contexts.

Conceptual Clarification

To clarify these abstract adversarial concepts, consider the following analogies:

- Adversarial debiasing functions like a sophisticated information filter system in a classified document environment. The primary classifier (predictor) tries to extract meaningful information for authorized purposes, while a security auditor (adversary) continuously monitors whether protected information is leaking through. When the auditor detects protected information, the classifier's methodology is adjusted to filter it out. Over time, this adversarial relationship creates a classifier that can extract useful information while provably protecting sensitive details—similar to how adversarial debiasing produces models that make accurate predictions while protecting sensitive attributes.

- The minimax game in adversarial debiasing resembles a basketball training scenario where a shooter practices against an increasingly adaptive defender. The shooter (predictor) aims to score baskets (accurate predictions) while the defender (adversary) tries to block shots based on reading the shooter's patterns. When the defender successfully anticipates the shooter's moves by recognizing patterns related to protected attributes, the shooter must develop new techniques that remain effective but don't reveal these patterns. The equilibrium is reached when the shooter can score consistently while the defender cannot predict shots based on protected characteristics.

- Optimization dynamics in adversarial training are similar to teaching two students with carefully balanced incentives. One student (the predictor) receives points for correct answers but loses points if they use certain prohibited shortcuts. Another student (the adversary) earns points specifically by catching the first student using these shortcuts. If the second student becomes too good too quickly, the first student may give up entirely; if the second student is ineffective, the first student will rely on shortcuts. The teacher must carefully adjust the reward structure and training pace to ensure both students improve appropriately—just as developers must carefully manage adversarial training dynamics to achieve both fairness and performance.

Intersectionality Consideration

Adversarial debiasing must explicitly address how multiple protected attributes interact to create unique fairness challenges at demographic intersections. Traditional implementations often train separate adversaries for each protected attribute, potentially missing complex discriminatory patterns that operate at intersections.

As Crenshaw (1989) established in her foundational work, discrimination often manifests differently at intersections of multiple identities, creating unique challenges that single-attribute analyses miss. For AI systems, this means adversarial approaches must be designed to prevent discrimination not just against individual protected groups but also against specific intersectional subgroups.

Recent work by Subramanian et al. (2021) demonstrates how adversarial architectures can be extended to address intersectionality by:

- Designing adversaries that predict combinations of protected attributes rather than individual attributes

- Implementing multi-task adversaries that simultaneously predict multiple protected attributes

- Employing hierarchical adversarial structures that address both individual attributes and their intersections

- Developing adversarial objectives that explicitly penalize discrimination against intersectional subgroups

Their research shows that these approaches can significantly improve fairness at demographic intersections compared to standard adversarial implementations that address protected attributes independently.

For the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit, addressing intersectionality requires explicit architectural and optimization considerations that extend beyond single-attribute approaches. Your framework should guide practitioners in implementing adversarial techniques that protect all demographic subgroups, including those at intersections that might otherwise receive inadequate protection from standard implementations.

3. Practical Considerations

Implementation Framework

To effectively implement adversarial debiasing in practice, follow this structured methodology:

-

Architectural Design:

-

Select an appropriate base architecture for the predictor component based on your primary task requirements.

- Design the adversary architecture with complexity proportional to the difficulty of protected attribute prediction.

- Implement a gradient reversal layer or equivalent mechanism between predictor and adversary.

-

Establish appropriate information flow connections based on your fairness definition:

- For demographic parity: Connect the adversary to the predictor's output

- For equalized odds: Connect the adversary to both the predictor's output and the true labels

- For representation fairness: Connect the adversary to the predictor's internal representations

-

Loss Function Formulation:

-

Define the primary task loss (e.g., cross-entropy for classification, mean squared error for regression).

- Formulate the adversarial loss (typically cross-entropy for protected attribute prediction).

-

Construct the combined objective with appropriate weighting:

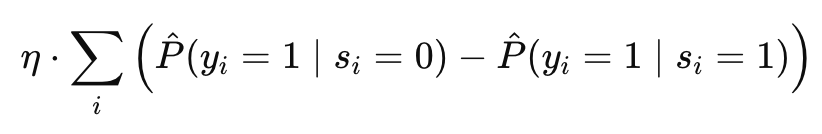

L_combined = L_primary - λ * L_adversarial -

Implement a schedule for the adversarial weight λ that increases gradually during training.

-

Training Procedure:

-

Initialize both predictor and adversary components with appropriate weights.

- Implement a progressive training schedule:

- Begin with a low weight for the adversarial component (small λ)

- Gradually increase λ as training progresses

- Potentially employ alternating optimization phases if stability issues arise

- Monitor both primary task performance and protected attribute leakage throughout training.

- Implement early stopping based on a combined metric that balances performance and fairness.

These methodologies integrate with standard ML workflows by extending conventional training procedures with additional components and objectives. While they add complexity to model development, they provide powerful fairness guarantees that may be difficult to achieve through other approaches.

Implementation Challenges

When applying adversarial debiasing, practitioners commonly face several challenges:

-

Training Instability: Adversarial training often suffers from instability due to competing objectives. Address this by:

-

Implementing gradient penalty terms that promote smoother optimization landscapes

- Using progressive training schedules with careful learning rate management

- Monitoring loss trajectories for signs of instability (e.g., oscillation, mode collapse)

-

Employing techniques like spectral normalization to stabilize adversary training

-

Architecture Balancing: The relative capacity of predictor and adversary significantly affects outcomes. Address this by:

-

Ensuring the adversary is powerful enough to learn protected attributes if they are present

- Preventing the adversary from becoming too powerful too quickly, which can destabilize training

- Experimenting with different architectural complexities to find an appropriate balance

- Implementing regularization that prevents either component from dominating

Successfully implementing adversarial debiasing requires computational resources for training and monitoring multiple network components, expertise in adversarial training techniques, and patience for the experimental tuning often needed to achieve stable and effective results.

Evaluation Approach

To assess whether your adversarial debiasing implementation is effective, implement these evaluation strategies:

-

Protected Attribute Leakage Testing:

-

Train separate "probe" classifiers that attempt to predict protected attributes from model outputs or representations

- Calculate mutual information between protected attributes and model representations

- Compare leakage metrics before and after adversarial training

-

Test leakage across intersectional demographic categories, not just main groups

-

Fairness-Performance Trade-off Analysis:

-

Plot Pareto frontiers showing the trade-off between primary task performance and fairness metrics

- Identify knee points on these frontiers that represent optimal trade-offs

- Compare adversarial results with those from other fairness approaches (constraints, regularization)

- Calculate the "price of fairness" in terms of performance reduction per fairness improvement

These evaluation approaches should be integrated with your organization's broader fairness assessment framework, providing specialized metrics for adversarial techniques while enabling comparison with alternative fairness interventions.

4. Case Study: Resume Screening System

Scenario Context

A large corporation is developing an automated resume screening system to help their HR department process the high volume of job applications they receive. The system analyzes resume text and work history to predict candidate suitability for different roles, producing a "qualification score" that helps prioritize applications for human review.

Initial testing revealed concerning disparities: the system consistently assigned lower qualification scores to female candidates compared to males with similar qualifications. Further analysis showed this bias stemmed partly from the training data (historical hiring decisions that favored men) and partly from the system learning to associate gender-correlated language patterns with qualification.

The data science team wants to implement fairness interventions while maintaining the system's ability to identify truly qualified candidates. They've already tried pre-processing approaches (modifying training data to balance gender representation), but these interventions either insufficiently addressed the bias or significantly reduced model performance.

The team decides to explore adversarial debiasing as an in-processing approach that might better balance fairness and performance. They face several challenges: the complex neural network architecture makes constraint-based methods difficult to implement; the text-based inputs create subtle patterns that correlate with gender; and they need to ensure fairness across intersectional categories (gender, race, age) while maintaining strong predictive performance.

Problem Analysis

Applying adversarial debiasing concepts to this scenario reveals several key considerations:

- Architectural Design: The resume screening system uses a neural network with text embeddings as input features. An adversarial approach would require adding an adversary network that attempts to predict applicant gender from either the qualification score (for demographic parity) or both the score and the ground truth qualification label (for equalized odds).

-

Protected Information Pathways: Gender information enters the system in multiple ways:

-

Explicit indicators (e.g., women's colleges, gender-specific organizations)

- Implicit patterns in language use (e.g., different adjective choices documented in research)

- Employment gaps or part-time work that correlate with gender due to social factors

-

Educational backgrounds that correlate with gender due to historical patterns

-

Adversarial Objective: The team needs to decide which fairness definition best suits their goals. Demographic parity would ensure equal qualification rate distributions across genders, while equalized odds would ensure equal true positive and false positive rates, potentially better preserving the system's ability to identify truly qualified candidates.

- Intersectional Considerations: Testing revealed that bias was particularly pronounced for certain intersectional groups, such as women over 40 and women from certain ethnic backgrounds. A standard adversarial approach addressing only gender might fail to protect these specific intersectional groups.

The key challenge is designing an adversarial system that effectively removes gender information from qualification predictions while maintaining the model's ability to identify truly qualified candidates based on legitimate qualification signals.

Solution Implementation

To address these challenges through adversarial debiasing, the team implemented a structured approach:

-

Architectural Implementation:

-

They designed a base neural network with text embedding inputs, followed by several hidden layers that produce the qualification score.

- They added an adversary network connected to both the qualification score output and intermediate representations from the base network.

- They implemented a gradient reversal layer between the main network and the adversary to enable the minimax training process.

-

They designed the adversary to predict not just gender, but also intersectional categories (combinations of gender, age range, and ethnicity).

-

Loss Function Formulation:

-

Primary loss: Binary cross-entropy based on historical hiring decisions (qualified/not qualified)

- Adversarial loss: Multi-task loss predicting protected attributes (gender, age range, ethnicity, and their intersections)

- Combined objective: L_combined = L_primary - λ * L_adversarial

-

Progressive weighting: Starting with λ = 0.1 and gradually increasing to 1.0 during training

-

Training Implementation:

-

They initialized both networks with pre-trained weights from a standard resume screening model.

- They implemented a progressive training schedule that gradually increased the adversarial component weight.

- They monitored both qualification prediction accuracy and protected attribute leakage throughout training.

-

They used early stopping based on a combined metric that balanced qualification prediction performance against fairness metrics.

-

Evaluation and Tuning:

-

They evaluated demographic parity by measuring differences in average qualification scores across gender groups.

- They assessed equalized odds by measuring differences in true positive and false positive rates.

- They tested for intersectional fairness by examining score distributions across different demographic subgroups.

- They iteratively adjusted the adversarial weight and architecture based on these evaluations.

Throughout implementation, they maintained explicit focus on intersectional effects, ensuring that the adversarial component prevented discrimination not just against women overall but against specific intersectional groups that were particularly vulnerable to bias.

Outcomes and Lessons

The adversarial implementation produced significant improvements compared to both the original biased model and alternative fairness interventions:

- The qualification score gap between male and female candidates decreased by 87%, substantially better than the 62% reduction achieved through pre-processing.

- The system maintained 92% of its original performance in identifying truly qualified candidates, compared to only 84% when using constraint-based approaches.

- Intersectional fairness improvements were more consistent than with other methods, with qualification score gaps decreasing by at least 75% across all demographic subgroups.

Key challenges included:

- Initial training instability that required careful tuning of learning rates and component scheduling

- Finding the right balance between the complexity of the adversary and main network

- Determining the optimal weight for the adversarial component (λ) to balance fairness and performance

The most generalizable lessons included:

- Architecture matters significantly: The specific design of the adversary and its connections to the main network dramatically affected both fairness and stability.

- Progressive training is crucial: Starting with a small adversarial weight and gradually increasing it produced much better results than using a fixed weight throughout training.

- Explicit intersectional design is necessary: Adversaries designed to protect specific intersectional groups performed substantially better than those targeting only primary demographic categories.

- Representation protection is powerful: Connecting the adversary to internal representations as well as outputs provided stronger fairness guarantees than output-only connections.

These insights directly inform the development of the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit in Unit 5, particularly in creating guidance for implementing effective adversarial debiasing across different model types and fairness definitions.

5. Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Adversarial Vs. Constraint-Based Approaches

Q: When should I use adversarial debiasing instead of the constraint-based approaches covered in Unit 1, and what are the key trade-offs between these methods?

A: Adversarial debiasing typically offers advantages over constraint-based approaches when working with complex models, non-convex objectives, or when flexibility in fairness-performance trade-offs is important. The key differences include: First, architectural compatibility - adversarial methods work naturally with neural networks and other complex architectures where explicit constraints are difficult to formulate or enforce, making them ideal for deep learning models. Second, optimization flexibility - adversarial approaches typically provide smoother trade-offs between fairness and performance compared to hard constraints, allowing more granular control through the adversarial weight parameter. Third, representational fairness - adversarial methods can protect internal representations, not just outputs, potentially addressing deeper forms of bias that constraints might miss. However, adversarial approaches generally require more computational resources, introduce greater training complexity, and offer weaker theoretical guarantees than constraint methods. Choose adversarial debiasing when working with neural networks, dealing with complex inputs like text or images, or when you need to fine-tune the fairness-performance balance. Prefer constraint-based approaches when working with simpler models (linear, convex), when strong theoretical guarantees are required, or when computational resources are limited.

FAQ 2: Implementation Stability Challenges

Q: My adversarial debiasing implementation is unstable during training, with oscillating losses and inconsistent results. What practical techniques can improve stability without sacrificing fairness or performance?

A: Training instability is a common challenge with adversarial methods, but several practical techniques can significantly improve stability: First, implement progressive scheduling - start with a very small adversarial weight (λ ≈ 0.01) and gradually increase it following a schedule (linear, exponential, or sigmoid), which allows the primary task to establish good representations before enforcing fairness. Second, use learning rate asymmetry - typically set the adversary's learning rate to be 2-5× lower than the predictor's rate to prevent oscillations; if the adversary becomes too powerful too quickly, training will destabilize. Third, apply gradient clipping and normalization to prevent extreme gradient values that can derail training. Fourth, consider pretraining the primary model without the adversary, then freezing earlier layers while fine-tuning with adversarial components. Fifth, implement spectral normalization on the adversary to limit its capacity and promote Lipschitz continuity, which significantly improves stability. Sixth, monitor both losses during training and implement early stopping with a patience mechanism that triggers when oscillations become severe. Finally, consider alternating update schedules where you update the predictor and adversary in separate phases rather than simultaneously. These techniques often need to be combined and tuned for your specific model, but together they can transform an unstable implementation into a reliable training process.

6. Project Component Development

Component Description

In Unit 5, you will develop the adversarial debiasing section of the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit. This component will provide structured guidance for selecting, implementing, and optimizing adversarial approaches across different model architectures and fairness definitions.

The deliverable will include architectural patterns for different fairness goals, implementation templates with stability mechanisms, and decision criteria for determining when adversarial approaches are most appropriate compared to other in-processing techniques.

Development Steps

- Create Architectural Pattern Templates: Develop standardized architectural patterns for implementing adversarial debiasing across different model types and fairness definitions. Include specific patterns for demographic parity, equalized odds, and representation fairness, with variations for different base architectures (feed-forward networks, CNNs, RNNs, transformers).

- Design Implementation Guidance: Create practical implementation templates with code patterns for gradient reversal, loss function formulation, and progressive training schedules. Include specific guidance on hyperparameter selection, component balance, and stability mechanisms.

- Develop Selection Criteria: Build decision frameworks for determining when adversarial approaches are more appropriate than constraints, regularization, or multi-objective methods. Create comparison matrices highlighting the strengths, limitations, and appropriate use cases for each approach.

Integration Approach

This adversarial component will interface with other parts of the In-Processing Fairness Toolkit by:

- Building on the constraint-based approaches from Unit 1, positioning adversarial methods as alternatives particularly suited for complex models.

- Establishing connections to the regularization approaches from Unit 3, highlighting how adversarial and regularization techniques can be combined.

- Providing inputs to the multi-objective optimization approaches in Unit 4, showing how adversarial objectives can be incorporated into explicit trade-off formulations.

To enable successful integration, clearly document the interfaces between adversarial and other approaches, including when they complement each other versus when they offer alternative implementation paths. Develop consistent terminology and evaluation metrics across components to facilitate comparison and integration.

7. Summary and Next Steps

Key Takeaways

This Unit has explored the powerful paradigm of adversarial debiasing for incorporating fairness directly into model training. Key insights include:

- Architectural design is fundamental to adversarial debiasing, with competing networks structured to prevent discrimination while maintaining predictive performance. The specific connections between predictor and adversary components determine which fairness properties are enforced.

- Adversarial unlearning provides a distinctive approach to fairness by actively removing protected attribute information from model representations rather than simply constraining outputs. This enables deeper fairness protections, particularly for complex models.

- Training dynamics require careful management to achieve both stability and effectiveness. Techniques like progressive scheduling, gradient reversal, and component balancing are essential for successful implementation.

- Intersectional fairness demands explicit consideration in adversarial approaches, with specialized architectures and objectives needed to protect overlapping demographic groups.

These concepts directly address our guiding questions by demonstrating how adversarial techniques can prevent models from encoding discriminatory patterns while maintaining performance, and by establishing the architectural and optimization principles that enable effective implementation.

Application Guidance

To apply these concepts in your practical work:

- Start by analyzing whether your model architecture and fairness requirements align well with adversarial approaches. Complex models with representational bias are typically good candidates.

- Design your adversarial architecture carefully, ensuring the adversary connects to the appropriate predictor outputs or representations based on your specific fairness definition.

- Implement progressive training schedules that gradually increase the adversarial weight, allowing the primary task to establish good representations before enforcing fairness constraints.

- Monitor both primary task performance and protected attribute leakage throughout training, using these metrics to tune the adversarial weight and architecture.

If you're new to adversarial techniques, begin with simpler architectural designs and gradually incorporate more advanced features like multi-task adversaries or representation protection as you gain experience. Start with small adversarial weights (λ ≈ 0.1) and conservative learning rates to ensure training stability while you learn the dynamics of these systems.

Looking Ahead

In the next Unit, we will explore regularization approaches to fairness, which offer a more flexible alternative to both constraints and adversarial methods. You will learn how carefully designed penalty terms can guide models toward fairer solutions without the complexity of adversarial training or the rigidity of constraints.

The adversarial techniques you've learned in this Unit complement these regularization approaches in important ways. While adversarial methods excel at preventing protected attribute information from being encoded in representations, regularization can more easily target specific fairness metrics directly. By understanding both approaches, you'll be equipped to select the most appropriate technique for your specific modeling context and fairness requirements.

References

Beutel, A., Chen, J., Zhao, Z., & Chi, E. H. (2017). Data decisions and theoretical implications when adversarially learning fair representations. Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency in Machine Learning (FAT/ML).

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139-167.

Edwards, H., & Storkey, A. (2016). Censoring representations with an adversary. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

Louppe, G., Kagan, M., & Cranmer, K. (2017). Learning to pivot with adversarial networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30.

Madras, D., Creager, E., Pitassi, T., & Zemel, R. (2018). Learning adversarially fair and transferable representations. International Conference on Machine Learning, 3384-3393.

Subramanian, S., Chakraborty, S., & Slotta, J. (2021). Fairness through adversarially learned debiasing. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 386-396.

Zhang, B. H., Lemoine, B., & Mitchell, M. (2018). Mitigating unwanted biases with adversarial learning. Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 335-340.

Unit 3

Unit 3: Regularization for Fairness

1. Conceptual Foundation and Relevance

Guiding Questions